|

© Victor & Victoria Trimondi

The Shadow of the Dalai Lama – Part

I – 10. The aggressive myth of Shambhala

10. THE AGGRESSIVE MYTH OF SHAMBHALA

The role of the ADI BUDDHA or rather of the

Chakravartin is not just discussed in general terms in the Kalachakra Tantra, rather, in the “myth of

Shambhala” the Time Tantra presents concrete political objectives. In this

myth statements are made about the authority of the world monarch, the establishment

and administration of his state, the organization of his army, and about a

strategic schedule for the conquest of the planet. But let us first

consider what exactly the Shambhala

myth can be understood to be.

According to legend, the historical Buddha,

Shakyamuni, taught the king of Shambhala,

Suchandra, the Kalachakra

Mulatantra, and initiated him into the secret doctrine. The original

text contained 12,000 verses. It was later lost, but an abridged version

survived. If we use the somewhat arbitrary calendar of the Time Tantra as a

basis, the encounter between Shakyamuni and Suchandra took place in the

year 878 B.C.E. The location of the instruction was Dhanyakataka close to the Mount Vulture Heap near Rajagriha

(Rajgir) in southern India. After Suchandra had asked him for instruction,

the Buddha himself assumed the form of Kalachakra

and preached to him from a Lion Throne surrounded by numerous Bodhisattvas

and gods.

Suchandra reigned as the king of Shambhala, a legendary kingdom

somewhere to the north of India. He did not travel alone to be initiated in

Dhanyakataka, but was accompanied

by a courtly retinue of 96 generals, provincial kings and governors. After

the initiation he took the tantra teaching back with him to his empire

(Shambhala) and made it the state religion there; according to other

reports, however, this only happened after seven generations.

Suchandra recorded the Kalachakra Mulatantra from memory and composed a number of

comprehensive commentaries on it. One of his successors (Manjushrikirti)

wrote an abridged edition, known as the Kalachakra

Laghutantra, a compendium of the original sermon. This 1000-verse text

has survived in toto and still today serves as a central text.

Manjushrikirti’s successor, King Pundarika, composed a detailed commentary

upon the Laghutantra with the

name of Vimalaprabha (‘immaculate

light’). These two texts (the Kalachakra

Laghutantra and the Vimalaprapha)

were brought back to India in the tenth century by the Maha Siddha Tilopa, and from there reached Tibet, the “Land of

Snows” a hundred years later. But only fragments of the original text, the Kalachakra Mulatantra, have

survived. The most significant fragment is called Sekkodesha and has been commented upon the Maha Siddha Naropa.

Geography of the kingdom of Shambhala

The kingdom of Shambhala,

in which the Kalachakra teaching

is practiced as the state religion, is surrounded by great secrecy, just as

is its first ruler, Suchandra.

Then he is also regarded as an incarnation of the Bodhisattva Vajrapani, the “Lord of Occult

Knowledge”. For centuries the Tibetan lamas have deliberately mystified the

wonderland, that is, they have left the question of its existence or

nonexistence so open that one has to paradoxically say that it exists and it does not. Since it is a

spiritual empire, its borders can only be crossed by those who have been

initiated into the secret teachings of the Kalachakra Tantra. Invisible for ordinary mortal eyes, for centuries

the wildest speculation about the geographic location

Shambhala have circulated. In “concrete” terms, all that is known is

that it can be found to the north of India, “beyond the River Sitha”. But

no-one has yet found the name of this river on a map. Thus, over the course

of centuries the numerous Shambhala

seekers have nominated all the even conceivable regions, from Kashmir

to the North Pole and everywhere in between.

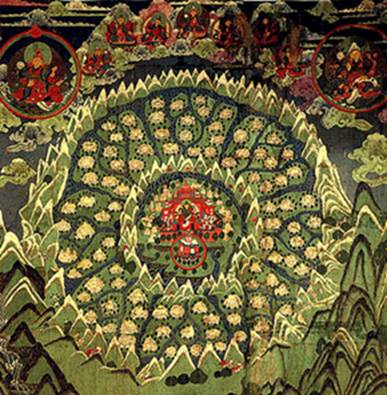

A

mandala of Shambhala

The most widespread opinion in the studies tends

toward seeking the original region in what is today the desert of the Tarim

Basin (Tarim Pendi). Many lamas

claim it still exists there, but is screened from curious eyes by a magical

curtain and is well guarded. Indeed, the syncretist elements which are to

be found in the Kalachakra Tantra

speak for the view that the text is a product of the ancient Silk Road

traversed by many cultures, which leads through the Tarim Basin. The huge

chain of mountains which surround the plateau in almost a circle also

concord with the geography of Shambhala.

Typically, the mythical map of Shambhala, of which

there are numerous reproductions, resembles a mandala. It has the form of a

wheel with eight spokes, or rather it corresponds

to a lotus with eight petals. Each of the petals forms an administrative

region. There a governor rules as the highest official. He is the viceroy

of not less than 120 million villages which can be found on each “lotus

petal”. Shambhala thus possesses

a total of 960 million settlements. The whole land is surrounded by a ring

of barely scaleable snowcapped mountains.

In the center of the ring of mountains lies the

country’s capital, Kalapa by name. By night, the city of light is lit up as

bright as day, so that the moon can no longer be seen. There the Shambhala king lives in a palace

made from every conceivable gem and diamond. The architecture is based upon

the laws of the heavens. There is a sun temple and a moon temple, a replica

of the zodiac and the astral orbits. A little to the south of the palace

the visitor finds a wonderful park. In it Suchandra ordered the temple of Kalachakra and Vishvamata

to be built. It is made from five valuable materials: gold, silver,

turquoise, coral, and pearl. Its ground plan corresponds to the Kalachakra sand mandala.

The kings and administration of Shambhala

All the kings of Shambhala belong to an inherited dynasty. Since the historical

Buddha initiated the first regent, Suchandra, into the Time Tantra there

have been two royal houses which have determined the fate of the country.

The first seven kings called themselves Dharmaraja

(kings of law). They were originally descended from the same lineage which

produced Buddha Shakyamuni, the Shakyas. The following 25 kings of the

second dynasty are the “Kulikas” or “Kalkis”. Each of these rulers reigns

for exactly 100 years. The future regents are also already laid down by

name. The texts are not always unanimous about who is presently ruling the

realm. Most frequently, King Aniruddha is named, who is said to have taken

the reins of power in 1927 and shall set them aside again in the year 2027.

A great spectacle awaits the world when the 25th scion of the Kalki dynasty

takes office. This is Rudra Chakrin,

the wrathful wheel turner. In the year 2327 he will ascend the throne. We

shall come to deal with him in detail.

Like the Indian Maha Siddhas, the Kalkis have long hair which they tie up in a

knot. Likewise, they also adorn themselves with earrings and armbands. “The

Kalki has excellent ministers, generals, and a great many queens. He has a

bodyguard, elephants and elephant trainers, horses, chariots, and

palanquins. His own wealth and the wealth of his subjects, the power of his

magic spells, the nagas, demons, and goblins that serve him, the wealth offered

to him by the centaurs and the quality of his food are all such that even

the lord of the gods cannot compete with him. ... The Kalki does not have

more than one or two heirs, but he has many daughters who are given as vajra ladies during the initiations

held on the full moon of Caitra

each year” (Newman, 1985, p. 57). It thus appears they serve as mudras in the Kalachakra rituals.

The ruler of Shambhala

is a absolute monarch and has at his disposal

the entire worldly and spiritual power of the country. He stands at the

apex of a “hierarchical pyramid” and the foundations of

his Buddhocracy is composed of an army of millions of viceroys,

governors, and officers who carry out the decrees of the regent.

As spiritual ruler, he is the representative of

the ADI BUDDHA, as “worldly” potentate a Chakravartin. He is seated upon a golden throne, supported by

eight sculptured lions. In his hands he holds a jewel which grants him

every wish and a magic mirror, in which he can observe and control

everything in his realm and on earth. Nothing escapes his watchful eye. He

has the ability and the right to look into the deepest recesses of the

souls of his subjects, indeed of anybody.

The roles of the sexes in the realm of Shambhala

are typical. It is exclusively men who exercise political power in the

androcentric state. Of the women we hear only something of their role as

queen mother, the bearer of the heir to the throne, and as “wisdom

consorts”. In the “tantric economy” of the state budget they form a

reservoir of vital resources, since they supply the “gynergy” which is transformed by the official sexual magic

rites into political power. Alone the sovereign has a million (!) girls,

“young as the eight-day moon”, who are available to be his partners.

The highest elite of the country is formed by the

tantric clergy. The monks wear white, speak Sanskrit, and are all initiated

into the mysteries of the Kalachakra

Tantra. The majority of them are considered enlightened. Then come the warriors. The king is at the same time the

supreme commander of a disciplined and extremely potent army with generals

at its head, a powerful officer corps and obedient “lower ranks”. The most

effective and “modern” weapons of destruction are stored in the extensive

arsenals of Shambhala. Yet — as

we shall later see — the army will only mobilize completely in three

hundred years time (2327 C.E.).

The totalitarian power of the Shambhala king

extends over not just the inhabitants of his country, but likewise over all

the people of our planet, “earth”. The French Kalachakra enthusiast, Jean Rivière, describes the

comprehensive competencies of the Buddhist despots as follows: “As master

of the universe, emperor of the world, spiritual regent over the powerful

subtle energy flows which regulate the cosmic order just as [they do] the

lives of the people, the Kulika [king] of Shambhala directs the spiritual development of the human masses

who were born into the heavy and blind material [universe]" (Rivière,

1985, p. 36). [1]

The “sun chariot” of the

Rishis

Although all its rulers are known by name, the Shambhala realm has no history in

the real sense. Hence in the many centuries of its existence hardly

anything worthy of being recorded in a chronicle has happened. Consider in

contrast the history-laden chain of events in the life of Buddha Shakyamuni

and the numerous legends which he left behind him! But there is an event

which shows that this country was not entirely free of historical conflict.

This concerns the protest of a group of no less than 35 million (!) Rishis (seers) led by the sage

Suryaratha ("sun chariot”).

As the first Kulika king, Manjushrikirti,

preached the Kalachakra Tantra to

his subjects, Suryaratha distanced himself from it, and his followers, the

Rishis, joined him. They preferred to choose banishment from Shambhala than

to follow the “diamond path” (Vajrayana).

Nonetheless, after they had set out in the direction of India and had

already crossed the border of the kingdom, Manjushrikirti sank in to a deep

meditation, stunned the emigrants by magic and ordered demon birds to bring

them back.

This event probably concerns a confrontation

between two religious schools. The Rishis worshipped only the sun. For this

reason they also called their guru the “sun chariot” (suryaratha). But the Kulika king had as Kalachakra master and cosmic androgyne united both heavenly

orbs in himself. He was the master of sun and moon. His demand of the Rishis

that they adopt the teachings of the Kalachakra

Tantra was also enacted on a night of the full moon. Manjushrikirti

ended his sermon with the words: “If

you wish to enter that path, stay here, but if you do not, then leave und

go elsewhere; otherwise the doctrines of the barbarians will com to spread

even in Shambhala.” (Bernbaum, 1980, p. 234).

The Rishis decided upon the latter. “Since we all

want to remain true to the sun chariot, we also do not wish to give up our

religion and to join another”, they rejoined (Grünwedel, 1915, p. 77). This

resulted in the exodus already outlined. But in fetching them back

Manjushrikirti had proved his magical superiority and demonstrated that the

“path of the sun and moon” is stronger than the “pure sun way”. The Rishis

thus brought him many gold tributes and submitted to his power and the

primacy of the Kalachakra Tantra.

In the fifteenth night of the moon enlightenment was bestowed upon them.

Behind this unique historical Shambhala incident hides a barely noticed power-political

motif. The seers (the Rishis)

were as their name betrays clearly Brahmans; they were members of the elite

priestly caste. In contrast, as priest-king Manjushrikirti integrated in

his office the energies of both the priestly and the military elite. Within

himself he united worldly and spiritual power, which — as we have

already discussed above — are allotted separately to the sun (high priest)

and the moon (warrior king) in the Indian cultural sphere. The union of

both heavenly orbs in his person made him an absolute ruler.

Because of the Shambhala

realm’s military plans for the future, which we will describe a little

later, the king and his successors are extremely interested in

strengthening the standing army. Then Shambhala

will need an army of millions for the battles which are in store for

it, and centuries count for nothing in this mythic realm. It was thus in

Manjushrikirti’s interest to abolish all caste distinctions in an

overarching militarily oriented Buddhocracy. The historical Buddha is

already supposed to have prophesied that the future Shambhala king, “.. possessing

the Vajra family, will become

Kalki by making the four castes into an single clan, within the Vajra family, not making them into a

Brahman family” (Newman, 1985, p. 64). The “Vajra family” mentioned is clearly contrasted to the priestly

caste in this statement by Shakyamuni. Within the various Buddha families

as well it represents the one who is responsible for military matters. Even

today in the West, high-ranking Tibetan lamas boast that they will be

reborn as generals (!) in the Shambhala

army, that is, that they think to transform their spiritual office into

a military one.

The warlike intention behind this ironing out of

caste distinctions becomes more obvious in Manjushrikirti’s justification

that the land, should it not follow Vajrayana

Buddhism, would inevitably fall into the hands of the “barbarians”. These —

as we shall later show — were the followers of Islam, against whom an

enormous Shambhala military was

being armed.

The journey to Shambhala

The travel reports written by Shambhala seekers are mostly kept so that we do not know

whether they concern actual experiences, dreams, imaginings, phantasmagoria

or initiatory progress. There is also no effort to keep these distinctions

clear. A Shambhala journey simply

embodies all of these together. Thus the difficult and hazardous adventures

people have undertaken in search of the legendary country correspond to the

“various mystical practices along the way, that

lead to the realization of tantric meditation in the kingdom itself. ...

The snow mountains surrounding Shambhala

represent worldly virtues, while the King in the center symbolizes the

pure mind at the end of the journey” (Bernbaum, 1980, p. 229).

In such interpretations, then, the journeys take

place in the spirit. Then again, this is not the impression gained by

leafing through the Shambha la’i lam

yig, the famous travel report of the Third Panchen Lama (1738–1780).

This concerns a fantastic collection , which is

obviously convinced of the reality of its factual material, of historical

and geographic particulars from central Asia which describe the way to Shambhala.

The landscapes which, according to this “classic

travel guide”, a visitor must pass through before entering the wonderland,

and the dangerous adventures which must be undergone, make the journey to

Shambhala (whether real or imaginary) a tantric initiatory way. This

becomes particularly clear in the central confrontation with the feminine

which just like the Vajrayana

controls the whole travel route. The quite picturesque book describes over

many pages encounters with all the female figures whom

we already know from the tantric milieu. With literary leisure the author

paints the sweetest and the most terrible scenes: pig-headed goddesses;

witches mounted upon boars; dakinis swinging skull bowls filled with blood,

entrails, eyes and human hearts; girls as beautiful as lotus flowers with

breasts that drip nectar; harpies; five hundred demonesses with copper-red

lips; snake goddesses who like nixes try to pull one into the water; the

one-eyed Ekajati; poison mixers;

sirens; naked virgins with golden bodies; female cannibals; giantesses;

sweet Asura girls with horse’s

heads; the demoness of doubt; the devil of frenzy; healers who give

refreshing herbs — they all await the brave soul who sets out to seek the

wonderland.

Every encounter with these female creatures must

be mastered. For every group the Panchen Lama has a deterrent, appeasing,

or receptive ritual ready. Some of the women must be turned away without

fail by the traveler, others should be honored and acknowledged, with yet others he must unite in tantric love. But woe betide him if he should lose his emotional and

seminal control here! Then he would become the victim of all these “beasts”

regardless of whether they appear beautiful or dreadful. Only a complete

tantra expert can pursue his way through this jungle of feminine bodies.

Thus the spheres alternate between the external

and the internal, reality and imagination, the world king in the hearts of

individual people and the real world ruler in the Gobi Desert, Shambhala as everyday life and Shambhala as a fairytale dream, and

everything becomes possible. When on his travels through Inner Asia the

Russian painter, Nicholas Roerich, showed some nomads photographs of New

York they cried out: “This is the land of Shambhala!” (Roerich, 1988, p.

274).

The “raging wheel turner”: The martial ideology of Shambhala

In the year 2327 (C.E.) — the prophecies of the Kalachakra Tantra tell us — the 25th

Kalki will ascend the throne of Shambhala.

He goes by the name of Rudra Chakrin,

the “wrathful wheel turner” or the “Fury with the wheel”. The mission of

this ruler is to destroy the “enemies of the Buddhist teaching” in a huge

eschatological battle and to found a golden age. This militant hope for the

future still today occupies the minds of many Tibetans and Mongolians and

is beginning to spread across the whole world. We shall consider the

fascination which the archetype of the “Shambhala

warrior” exercises over western Buddhists in more detail later.

Rudra Chakrin – the militant messiah of

Shambhala

The Shambhala

state draws a clear and definite distinction between friend and enemy.

The original idea of Buddhist pacifism is completely foreign to it. Hence the

Rudra Chakrin carries a martial

symbolic object as his insignia of dominion, the “wheel of iron” (!).We may

recall that in the Buddhist world view our entire universe (Chakravala) is enclosed within a

ring of iron mountains. We have interpreted this image as a reminder of the

“doomsday iron age” of the prophecies of antiquity.

Mounted upon his white horse, with a spear in his

hand, the Rudra Chakrin shall

lead his powerful army in the 24th century. “The Lord of the Gods”, it is

said of him in the Kalachakra Tantra,

“ joined with the twelve lords shall go to destroy

the barbarians” (Newman, 1987, p. 645). His army shall consist of

“exceptionally wild warriors” equipped with “sharp weapons”. A hundred

thousand war elephants and millions of mountain horses, faster than the

wind, shall serve his soldiers as mounts. Indian gods will then join the

total of twelve divisions of the “wrathful wheel turner” and support their

“friend” from Shambhala. This support for the warlike Shambhala king is probably due to his predecessor,

Manjushrikirti, who succeeded in integrating the 120 million Hindu Rishis

into the tantric religious system (Banerjee, 1985, p. xiii).

If, as legend has it, the author of the Kalachakra Tantra was the historical

Buddha, Shakyamuni, in person, then he must have forgotten his whole vision

and message of peace and had a truly great fascination for the military

hardware. Then weaponry plays a prominent role in the Time Tantra. Here

too, by “weapon” is understood every means of implementing the physical

killing of humans. It is also said of Buddha’s martial successor, the

coming Rudra Chakrin, that, “with

the sella (a deadly weapon) in

the hand ... he shall proclaim the Kalachakra

on earth for the liberation of beings” (Banerjee, 1959, p. 213).

Lethal war machines

The graphic description of the war machines to

which the Kalachakra deity

devotes a number of pages already in the first chapter of the tantra is

downright impressive and astonishing (Newman, 1987, pp. 553-570, verses

135-145; Grönbold, 1996). A total of seven exceptionally destructive arts

of weapon are introduced. All take the form of a wheel. The text refers to

them as yantras. There is a “wind

machine” which is primarily put into action against mountain forts. They

float over the enemy army and let burning oil run out all over them. The

same happens to the houses and palaces of the opponent. The second art of

weapon is described as a “sword in the ground machine”. This acts as a

personal protection for the “wrathful wheel turner”. Anyone who enters his

palace without permission and steps upon the machine hidden beneath the

floor is inevitably cut to pieces. As the third art follows the “harpoon

machine”, a kind of ancient machine gun. At the squeeze of a finger, “many

straight arrows or sharp Harpoons hat pierce and pass through the body of

an armored elephant” (Newman, 1987, p. 506).

We are acquainted with three further extremely

effective “rotating weapons” which shear everything away, above all the

heads of the enemy troops. One of them is compared to the wheels of the sun

chariot. This is probably a variant of the solar discus which the Indian

god Vishnu successfully put to

use against the demon hordes. Such death wheels have played a significant

role in Tibet’s magic military history right up into this century. We shall

return to this topic at a later point. These days, believers in the Shambhala myth see “aircraft” or

“UFOs” in them which are armed with atomic bombs and are guided by the

world king’s extraterrestrial support troops.

In light of the numerous murderous instruments

which are listed in the Kalachakra

Tantra, a moral problem obviously arose for some “orthodox” Buddhists

which led to the wheel weapons being understood purely symbolically. They

concerned radical methods of destroying one’s own human ego. The great

scholar and Kalachakra

commentator, Khas Grub je, expressly opposes this pious attempt. In his

opinion, the machines “are to be taken literally” (Newman, 1987, p. 561).

The “final battle”

Let us return to the Rudra Chakrin, the tantric apocalyptic redeemer. He appears in

a period, in which the Buddhist teaching is largely eradicated. According

to the prophecies, it is the epoch of the “not-Dharmas”, against whom he

makes a stand. Before the final battle against the enemies of Buddhism can

take place the state of the world has worsened dramatically. The planet is

awash with natural disasters, famine, epidemics, and war. People become

ever more materialistic and egoistic. True piety vanishes. Morals become

depraved. Power and wealth are the sole idols. A parallel to the Hindu

doctrine of the Kali yuga is

obvious here.

In these bad times, a

despotic “barbarian king” forces all nations other than Shambhala to follow his rule, so

that at the end only two great forces remain: firstly the depraved “king of

the barbarians” supported by the “lord of all demons “, and secondly Rudra Chakrin, the wrathful Buddhist

messiah. At the outset, the barbarian ruler subjugates the whole world

apart from the mythical kingdom of Shambhala. Its existence is an

incredible goad to him and his subjects: “Their jealousy will surpass all

limits, crashing up like waves of the sea. Incensed that there could be

such a land outside their control, they will gather an army together und

set out to conquer it.” (Bernbaum, 1980, p. 240). It then comes, says the prophecy, to a

brutal confrontation. [2]

Alongside the descriptions from the Kalachakra Tantra there are numerous

other literary depictions of this Buddhist apocalyptic battle to be found.

They all fail to keep secret their pleasure at war and the triumph over the

corpses of the enemy. Here is a passage from the Russian painter and Shambhala believer, Nicholas

Roerich, who became well known in the thirties as the founder of a

worldwide peace organization ("Banner of Peace”). “Hard is the

fate of the enemies of Shambhala. A just wrath colors the purple blue

clouds. The warriors of the Rigden-jyepo

[the Tibetan name for the Rudra

Chakrin], in splendid armor with swords and spears are pursuing their

terrified enemies. Many of them are already prostrated and their firearms,

big hats and all their possessions are scattered over the battlefield. Some

of them are dying, destroyed by the just hand. Their leader is already

smitten and lies spread under the steed of the

great warrior, the blessed Rigden.

Behind the Ruler, on chariots, follow fearful cannons, which no walls can

withstand. Some of the enemy, kneeling, beg for mercy, or attempt to escape

their fate on the backs of elephants. But the sword of justice

overtake defamers. The Dark must be annihilated.” (Roerich, 1985, p.

232) The “Dark”, that is

those of different faiths, the opponents of Buddhism and hence of

Shambhala. They are all cut down without mercy during the “final battle”.

In this enthused sweep of destruction the Buddhist warriors completely

forget the Bodhisattva vow which preaches compassion with all beings.

The skirmishes of the battle of the last days (in

the year 2327) are, according to commentaries upon the Kalachakra Tantra, supposed to reach through Iran into eastern

Turkey (Bernbaum, 1982, p. 251). The regions of the Kalachakra Tantra’s origin are also often referred to as the

site of the coming eschatological battlefield (the countries of Kazakhstan,

Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan). This has

a certain historical justification, since the southern “Islamic” flank of

the former Soviet Union counts as one of the most explosive crisis regions

of the present day (see in this regard the Spiegel, 20/1998, pp. 160-161).

The conquest of Kailash, the holy mountain, is

nominated as a further strategic goal in the Shambhala battle. After the Rudra Chakrin has “killed [his

enemies] in battle waged across the whole world, at the end of the age the

world ruler will with his own fourfold army come into the city which was

built by the gods on the mountain of Kailash” (Banerjee, 1959, p. 215). In

general, “wherever the [Buddhist] religion has been destroyed and the Kali age is on the rise, there he

will go” (Banerjee, 1959, p. 52). [3]

Buddha versus Allah

The armies of Rudra

Chakrin will destroy the “not-Dharma” and the doctrines of the

“unreligious barbarian hordes”. Hereby, according to the original text of

the Kalachakra Tantra, it is

above all the Koran which is

intended. Mohammed himself is referred to by name several times in the Time

Tantra, as is his one god, Allah.

We learn of the barbarians that they are called Mleccha, which means the “inhabitants of Mecca” (Petri, 1966,

p. 107). These days Rudra Chakrin

is already celebrated as the “killer of the Mlecchas” (Banerjee, 1959, p. 52). This fixation of the highest

tantra on Islam is only all too readily understandable, then the followers

of Mohammed had in the course of history not just wrought terrible havoc among

the Buddhist monasteries and communities of India — the Islamic doctrine

must also have appeared more attractive and feeling to many of the ordinary

populace than the complexities of a Buddhism represented by an elitist

community of monks. There were many “traitors” in central Asia who gladly

and readily reached for the Koran.

Such conversions among the populace must have eaten more deeply into the

hearts of the Buddhist monks than the direct consequences of war. Then the Kalachakra Tantra, composed in the

time where the hordes of Muslims raged in the Punjab and along the Silk

Road, is marked by an irreconcilable hate for the “subhumans” from Mecca.

This dualist division of the world between

Buddhism on the one side and Islam on the other is a dogma which the

Tibetan lamas seek to transfer to the future of the whole of human history.

“According to certain conjectures”, writes a western commentator upon the Shambhala myth, “two superpowers

will then have control over the world and take to the field against one

another. The Tibetans foresee a Third World War here” (Henss, 1985, p. 19).

In the historical part of our analysis we shall

come to speak of this dangerous antinomy once more. In contrast to

Mohammed, the other “false doctrines” likewise mentioned in the first

chapter of the Kalachakra Tantra

as needing to be combated by the Shambhala

king appear pale and insignificant. It nevertheless makes sense to

introduce them, so as to demonstrate which founders of religions the

tantric blanket conception of enemy stretched to encompass. The Kalachakra nominates Enoch, Abraham

and Moses among the Jews, then Jesus for the Christians, and a “white

clothed one”, who is generally accepted to be Mani, the founder the

Manichaeism. It is most surprising that in a further passage the “ false

doctrines “ of these religious founders are played down and even integrated

into the tantra’s own system. After they have had to let a strong attack

descend upon them as “heresies” in the first chapter, in the second they

form the various facets of a crystal, and the yogi is instructed not to

disparage them (Grönbold, 1992a, p. 295).

Such inconsistencies are — as we have already

often experienced — added to tantric philosophy by itself. The second

chapter of the Kalachakra Tantra

thus does not switch over to a western seeming demand for freedom of

religion and opinion, on the contrary apparent tolerance and thinking in

terms of “the enemy” are both retained alongside one another and are,

depending on the situation, rolled out to serve its own power interest. The

Fourteenth Dalai Lama is — as we shall show in detail — an ingenious

interpreter of this double play. Outwardly he espouses religious freedom

and ecumenical peace. But in contrast, in the ritual system he concentrates

upon the aggressive Time Tantra, in which the scenario is dominated by

destructive fantasies, dreams of omnipotence, wishes for conquest,

outbreaks of wrath, pyromaniacal obsessions, mercilessness, hate, killing

frenzies, and apocalypses. That such despotic images also determine the

“internal affairs” of the exiled Tibetans for the Tibetan “god-king”, is

something upon which we shall report in the second part of our study.

After winning the final battle, the Kalachakra Tantra prophecies, the Rudra Chakrin founds the “golden

age”. A purely Buddhist paradise is established on earth. Joy and wealth

will abound. There is no more war. Everybody possesses great magical

powers, Science and technology flourish. People

live to be 1800 years old and have no need to fear death, since they will

be reborn into an even more beautiful Eden. This blissful state prevails

for around 20,000 years. The Kalachakra

Tantra has by then spread to every corner of the globe and become the

one “true” world religion. (But afterwards, the old cycle with its wars of

destruction, defeats and victories begins anew.)

The non-Buddhist origins of the Shambhala myth

Apocalyptic visions, final battles between Good

and Evil, saviors with lethal weapons in their hands are absolutely no

topic for Hinayana Buddhism. They first emerge in the Mahayana period (200 B.C.E.), are

then incorporated by Vajrayana

(400 C.E.) and gain their final and central form in the Kalachakra Tantra (tenth century

C.E.). Hence, as in the case of the ADI BUDDHA, the question arises as to

where the non-Buddhist influences upon the Shambhala myth are to be sought.

Yet before we come to that, we ought to consider

the widespread Maitreya prophecy,

which collides with the Shambhala vision

and the Kalachakra Tantra.

Already in the Gandhara era (200 B.C.E.), Maitreya is known as the future Buddha who shall be incarnated

on earth. He is still dwelling in the so-called Tushita heaven and awaits his mission. Images of him strike the

observer at once because unlike other depictions of Buddha he is not

resting in the lotus posture, but rather sits in a “European” style, as if

on a chair. In his case too, the world first goes into decline before he

appears to come to the aid of the suffering humanity. His epiphany is,

however, according to most reports much more healing and peaceable than

those of the “wrathful wheel turner”. But there are also other more

aggressive prophecies from the seventh century where he first comes to earth

as a messiah following an apocalyptic final battle (Sponberg, 1988, p. 31).

For the Russian painter and Shambhala

seeker, Nicholas Roerich, there is in the end no difference between Maitreya and Rudra Chakrin any more, they are simply two names for the same

redeemer.

Without doubt the Kalachakra Tantra is

primarily dominated by conceptions which can also be found in Hinduism.

This is especially true of the yoga techniques, but likewise applies to the

cosmology and the cyclical destruction and renewal of the universe. In

Hindu prophecies too, the god Vishnu

appears as savior at the end of the Kali

yuga, also, incidentally, upon a white horse like the Buddhist Rudra Chakrin, in order to

exterminate the enemies of the religion. He even bears the dynastic name of

the Shambhala kings and is known

as Kalki.

Among the academic researchers there is

nonetheless the widespread opinion that the savior motif, be it Vishnu or Buddha Maitreya or even the Rudra

Chakrin, is of Iranian origin. The stark distinction between the forces

of the light and the dark, the apocalyptic scenario, the battle images, the

idea of a militant world ruler, even the mandala model of the five

meditation Buddhas were unknown among the original Buddhist communities.

Buddhism, alone among all the salvational religions, saw no savior behind

Gautama’s experience of enlightenment. But for Iran these motifs of

salvation were (and still are today) central.

In a convincing study, the orientalist, Heinrich

von Stietencron, has shown how — since the first century C.E. at the latest

— Iranian sun priests infiltrated into India and merged their concepts with

the local religions, especially Buddhism. (Stietencron, 1965. p. 170). They

were known as Maga and Bhojaka. The Magas, from whom our word “magician” is derived, brought with

them among other things the cult of Mithras and combined it with elements

of Hindu sun worship. Waestern researchers presume that the name of Maitreya, the future Buddha, derives

from Mithras.

The Bhojakas,

who followed centuries later (600–700 C.E.), believed that they emanated

from the body of their sun god. They also proclaimed themselves to be the

descendants of Zarathustra. In India they created a mixed solar religion

from the doctrines of the Avesta

(the teachings of Zarathustra) and Mahayana

Buddhism. From the Buddhists they adopted fasting and the prohibitions on

cultivating fields and trade. In return, they influenced Buddhism primarily

with their visions of light. Their “photisms” are said to have especially

helped shape the shining figure of the Buddha Amitabha. Since they placed the time god, Zurvan, at the center of their cult, it could also be they who

anticipated the essential doctrines of the Kalachakra Tantra.

Like the Kalachakra

deity we have described, the Iranian Zurvan

carries the entire universe in his mystic body: the sun, moon, and stars.

The various divisions of time such as hours, days, and months dwell in him

as personified beings. He is the ruler of eternal and of historical time.

White light and the colors of the rainbow burst out of him. His worshippers

pray to him as “father-mother”. Sometimes he is portrayed as having four

heads like the Buddhist time god. He governs as the “father of fire” or as

the “victory fire”. Through him, fire and time are equated. He is also

cyclical time, in which the world is swallowed by flames so as to arise

anew.

Manichaeism (from the third century on) also took

on numerous elements from the Zurvan

religion and mixed them with Christian/Gnostic ideas and added Buddhist

concepts. The founder of the religion, Mani, undertook a successful

missionary journey to India. Key orientalists assume that his teachings

also had a reverse influence upon Buddhism. Among other aspects, they

mention the fivefold group of meditation Buddhas, the dualisms of good and

evil, light and darkness, the holy man’s body as the world in microcosm,

and the concept of salvation. More specific are the white robes which the

monks in the kingdom of Shambhala wear.

White was the cult color of the Manichaean priestly caste and is not a

normal color for clothing in Buddhism. But the blatant eroticism which the Kalachakra translator and researcher

in Asia, Albert Grünwedel, saw in Manichaeism was not there. In contrast;

Mani’s religion exhibits extremely “puritanical” traits and rejects

everything sexual: “The sin of sex”, he is reported to have said, “is

animal, an imitation of the devil mating. Above all it produces every

propagation and continuation of the original evil” (quoted by Hermanns,

1965, p. 105).

While the famous Italian Tibetologist, Guiseppe

Tucci, believes Iranian influences can be detected in the doctrine of ADI

BUDDHA, he sees the Lamaist-Tibetan way in total rather as gnostic, since

it attempts to overcome the dualism of good and evil and does not peddle

the out and out moralizing of the Avesta

or the Manichaeans. This is certainly true for the yoga way in the Kalachakra Tantra, yet it is not so

for the eschatology of the Shambhala

myth. There, the “prince of light” (Rudra

Chakrin) and the depraved “prince of darkness” take to the field

against one another.

There was a direct Iranian influence upon the Bon

cult, the state religion which preceded Buddhism in Tibet. Bon, often

erroneously confused with the old shamanist cultures of the highlands, is a explicit religion of light with an organized

priesthood, a savior (Shen rab)

and a realm of paradise (Olmolungring)

which resembles the kingdom of Shambhala

in an astonishing manner.

It is a Tradition in Europe to hypothesize ancient

Egyptian influences upon the tantric culture of Tibet. This can probably be

traced to the occult writings of the Jesuit, Athanasius Kirchner

(1602-1680), who believed he had discovered the cradle of all advanced

civilizations including that of the Tibetans in the Land of the Nile. The

Briton, Captain S. Turner, who visited the highlands in the year 1783, was

likewise convinced of a continuity between ancient

Egypt and Tibet. Even this century, Siegbert Hummel saw the “Land of Snows”

as almost a “reserve for Mediterranean traditions” and likewise nominated

Egypt as the origin of the tradition of the Tibetan mysteries (Hummel,

1954, p. 129; 1962, p. 31). But it was especially the occultist Helena

Blavatsky who saw the origins of both cultures as flowing from the same

source. The two “supernatural secret societies”, who whispered the ideas to

her were the “Brotherhood of Luxor” and the

“Tibetan Brotherhood”.

The determining Greek influence upon the sacred

art of Buddhism (Gandhara style) became a global event which left its

traces as far afield as Japan. Likewise, the effect of Hellenistic ideas

upon the development of Buddhist doctrines is well vouched for. There is

widespread unanimity that without this encounter Mahayana would have never even been possible. According to the

studies of the ethnologist Mario Bussagli, hermetic and alchemic teachings

are also supposed to have come into contact with the world view of Buddha

via Hellenistic Baktria (modern Afghanistan) and the Kusha empire which

followed it, the rulers of which were of Scythian origin but had adopted

Greek language and culture (Bussagli, 1985).

Evaluation of the Shambhala myth

The ancient origins and contents of the Shambhala state make it, when seen

from the point of view of a western political scientist, an antidemocratic,

totalitarian, doctrinaire and patriarchal model. It concerns a repressive

ideal construction which is to be imposed upon all of humanity in the wake

of an “ultimate war”. Here the sovereign (the Shambhala king) and in no sense the people decide the legal

norms. He governs as the absolute monarch of a planetary Buddhocracy. King

and state even form a mystic unity, in a literal, not a figurative sense, then the inner bodily energy processes of the ruler are

identical with external state happenings. The various administrative levels

of Shambhala (viceroys, governors, and officials) are thus considered to be

the extended limbs of the sovereign.

Further to this, the Shambhala state (in contrast to the original teachings of the

Buddha) is based upon the clear differentiation of friend and enemy. Its

political thought is profoundly dualist, up to and including the moral

sphere. Islam is regarded as the arch-enemy of the country. In resolving

aggravated conflicts, Shambhala society

has recourse to a “high-tech” and extremely violent military machinery and

employs the sociopolitical utopia of “paradise on earth” as its central

item of propaganda.

It follows from all these features that the

current, Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s constant professions of faith in the

fundamentals of western democracy remain empty phrases for as long as he

continues to place the Kalachakra

Tantra and the Shambhala myth

at the center of his ritual existence. The objection commonly produced by

lamas and western Buddhists, that Shambhala concerns a metaphysical

and not a worldly institution, does not hold water. We know, namely, from

history that both traditional Tibetan and Mongolian society cultivated the Shambhala myth without at any stage

drawing a distinction between a worldly and a metaphysical aspect in this

matter. In both countries, everything which the Buddhocratic head of state

decided was holy per se.

The argument that the Shambhala vision was distant “pie in the sky” is also not

convincing. The aggressive warrior myth and the idea of a world controlling

ADI BUDDHA has influenced the history of Tibet and Mongolia for centuries

as a rigid political program which is oriented to the decisions of the

clerical power elite. In the second part of our study we present this

program and its historical execution to the reader. We shall return to the

topic that in the view of some lamas the Tibetan state represents an

earthly copy of the Shambhala realm

and the Dalai Lama an emanation of the Shambhala

king.

“Inner” and “outer” Shambhala

In answer to the question as to why the “world

ruler on the Lion Throne” (the Shambhala

king) does not peacefully and positively intervene in the fate of

humanity, the French Kalachakra

believer, Jean Rivière, replied: “He does not inspire world politics and

does not intervene directly or humanly in the conflicts of the reborn

beings. His role is spiritual, completely inner, individual one could say”

(Rivière, 1985, p. 36).

Such an “internalization” or “psychologization” of

the myth is applied by some authors to the entire Buddhocratic realm,

including the history of Shambhala and the final battle prophesied there.

The country, with all its viceroys, ministers, generals, officials,

warriors, ladies of the court, vajra

girls, palace grounds, administrative bodies and dogmata, now appears as a

structural model which describes the mystic body of a yogi: “If you can use

your body properly, than the body becomes Shambhala, the ninety-six

principalities concur in all their actions, and you conquer the kingdom

itself.” (Bernbaum, 1980, p. 155)

The arduous “journey to Shambhala” and the “final

battle” are also subjectified and identified as, respectively, an

“initiatory path” or an “inner battle of the soul” along the way to

enlightenment. In this psycho-mystic drama, the ruler of the last days, Rudra Chakrin, plays the “higher

self” or the “divine consciousness” of the yogi, which declares war on the

human ego in the figure of the “barbarian king” and exterminates it. The

prophesied paradise refers to the enlightenment of the initiand.

We have already a number of times gone into the

above all among western Buddhists widespread habit of exclusively

internalizing or “psychologizing” tantric images and myths. From an

“occidental” way of looking at things, an internalization

implies that an external image (a war for example) is to be understood as a

symbol for an inner psychic/spiritual process (for example, a

“psychological” war). However, according to Eastern, magic-oriented

thinking, the “identity” of interior and exterior means something

different, namely that the inner processes in the yogi’s mystic body

correspond to external events, or to tone this down a little , that inside and outside consist of the same

substance (of “pure spirit” for example). The external is thus not a

metaphor for the internal as in the western symbolic conception, but rather

both, inner and exterior, correspond to one another. Admittedly this

implies that the external can be influenced by inner manipulations, but not

that it thereby disappears. Applying this concept to the example mentioned

above results in the following simple statement: the Shambhala war takes place internally and externally. Just as the mystic body (interior) of the ADI

BUDDHA is identical with the whole cosmos (exterior), so the mystic body

(interior) of the Shambhala king

is identical to his state (exterior).

The Shambhala

myth and the ideologies derived from it stand in stark opposition to

Gautama Buddha’s original vision of peace and to the Ahimsa politics (politics of nonviolence) of Mahatma Ghandi, to

whom the current Dalai Lama so often refers. For Westerners sensitized by

the pacifist message of Buddhism, the “internalization” of the myth may

thus offer an way around the militant ambient of

the Kalachakra Tantra. But in

Tibetan/Mongolian history the

prophecy of Shambhala has been

taken literally for centuries, and — as we still have to demonstrate — has

led to extremely aggressive political undertakings. It carries within it —

and this is something to we shall return to discuss in detail — the seeds

of a worldwide fundamentalist ideology of war.

Footnotes:

[3] The scenario

of the Shambhala wars cannot be

easily brought into accord with the total downfall of the world instigated

by the tantra master which we have described

above. Rudra Chakrin is a commander who conducts his battles here on

earth and extends these to at best the other 11 continents of the Buddhist

model of the world. His opponents are above all the followers of

Allah. As global as his mission may

be, it is still realized within the framework of the existing cosmos. In other textual passages the coming Shambhala king is also compared with

the ADI BUDDHA, who at the close of the Kali

yuga lays waste to the entire universe and lets

loose a war of the stars. It is,

however, not the aim of this study to explicate such contradictions.

Next

Chapter:

11. THE MANIPULATOR OF

EROTIC LOVE

|