|

© Victor & Victoria Trimondi

The Shadow of the Dalai Lama – Part

II – 3. The Foundations of the Tibetan Buddhocracy

3. THE FOUNDATIONS OF THE TIBETAN BUDDHOCRACY

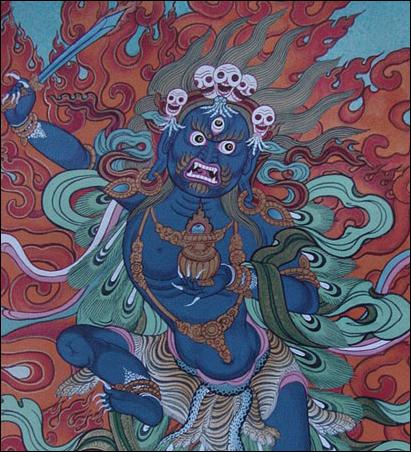

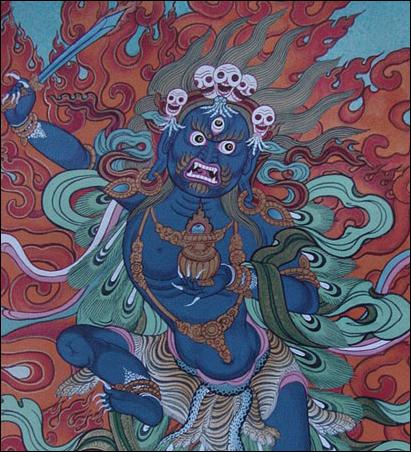

The cult drama of Tibetan/Tantric Buddhism consists

in the constant taming of the feminine, the demoness. This is heralded

already in the language. The Tibetan verb dulwa has the following meanings: to tame, subjugate, conquer,

defeat; and sometimes: to kill, destroy; but also: to cultivate the land,

civilize a nation, convert to Buddhism, bring up, discipline. Violent

conquest and cultural activities thus form a unit for the Lamaist. The

chief task of the Tibetan monastic state consists in the taming of

wilderness (wild nature), the “heathen” barbarians, and the women. In

tantric terminology this corresponds with the method (upaya) with which the feminine wildness (Candali or Srinmo) is

defeated. Parallel to this, state Buddhism and social anarchy stand opposed

to one another as enemies since the beginning of Tibetan history — they

conduct their primordial struggle in the political, social, philosophical,

divine, and cosmic arenas. Even though they battle to the bitter end, they

are nonetheless — as we shall see — dependent upon one another.

The history of Buddhist state thought

The fundamental attitude of the historical Buddha

was anarchist. Not only did he leave his family behind, the king’s son also

laid aside all offices of state. With the founding of the Buddhist

community (the sangha), he assumed

that this was a purely spiritual union which was ethically far superior to

worldly institutions. The sangha

formed the basic pattern for an ideal society, whilst the secular state was

constantly receiving karmic stains through its worldly business. For this

reason the relationship between the two institutions (the sangha and the state) was always

tense and displayed many discordances which had arisen even earlier — in

the Vedic period — between kshatriyas

(warriors and kings) and brahmans

(priests).

However, the anti-state attitude of the Buddhists

changed in the third century B.C.E. with the seizure of power by of the

Emperor Ashoka (who ruled between 272–236 B.C.E.) Ashoka, a ruler from the

Maurya dynasty, had conquered almost the entire Indian subcontinent

following several terrible campaigns. He converted to Buddhism and set

great store by the distribution of the religion of Shakyamuni throughout

the whole country. In accordance with the teaching, he forbade animal

sacrifices and propagated the idea of vegetarianism.

His state-political status is not entirely clear

among the historians, then a number of contradictory documents about this

are extant. In one opinion he and the whole state submitted to the rule of

the sangha (the monastic

community) and he let his decisions be steered by them. According to

another document, he himself assumed leadership of the community and became

a sangharaja (both king and

supreme commander of the monastic community). The third view is the most

likely — that although he converted to the Buddhist faith he retained his

political autonomy and forced the monastic community to obey his will as

emperor. In favor if this view is the fact that it was he who summoned a

council and there forced through his “Buddhological” ideas.

Up until today the idea of the just “king of

peace” has been celebrated in the figure of Ashoka, and it has been

completely overlooked that he confronted the sangha with the problem of state power. The Buddhist monastic

community was originally completely non-coercive. Following its connection

with the state, the principle of nonviolence necessarily came into conflict

with the power political requirements this brought with it. For example,

the historical Buddha is said to have had such an aversion to the death

penalty that he offered himself as a substitute in order to save the life

of a criminal. Ashoka, however, who proclaimed an edict against the

slaughter of animals, did not renounce the execution of criminals by the

state.

Whether during his lifetime or first due to later

interpretations — the Emperor was (at any rate after his demise) declared

to be a Chakravartin (world

ruler) who held the “golden wheel” of the Dharma (the teaching) in his hands. He was the first historical

Bodhisattva king, that is, a Bodhisattva incarnated in the figure of a

worldly ruler. In him, worldly and spiritual power were united in one

person. Interestingly he established his spiritual world domination via a

kind of “cosmic sacrifice”. Legend tells how the Emperor came into possession

of the original Buddha relic and ordered this to be divided into 84,000

pieces and scattered throughout the entire universe. Wherever a particle of

this relic landed, his dominion spread, that is, everywhere, since at that

time in India 84,000 was a symbolic number for the cosmic whole. [1] This pious account of his universal

sovereignty rendered him completely independent of the Buddhist sangha.

In the Mahayana

Golden Shine Sutra, a few centuries after Ashoka, the coercive power of

the state is affirmed and presented as a doctrine of the historical Buddha.

With this the anarchic period of the Sangha

was finally ended. By 200 C.E. at the latest, under the influence of

Greco-Roman and Iranian ideas, the Buddhist concept of kingship had

developed into its fully autocratic form which is referred to by historians

as “Caesaropapism”. An example of this is provided by King Kanishka from

the Kushana dynasty (2nd century C.E.) In him, the attributes of a worldly

king and those of a Buddha were completely fused with one another. Even the

“coming” Buddha, Maitreya, and

the reigning king formed a unit. The ruler had become a savior. He was a contemporary Bodhisattva and at the

same time the appearance of the coming

Buddhist messiah who had descended from heaven already in this life so as

to impart his message of salvation to the people. (Kanishka cultivated a

religious syncretism and also used other systems to apotheosize his person

and reign.)

The Dalai Lama and the Buddhist state are one

Tibet first became a centralized ecclesiastical

state with the Dalai Lama as its head in the year 1642. The priest-king had

the self-appointed right to exercise absolute power. He was de jure not just lord over his human subjects but likewise

over the spirits and all other beings which lived “above and beneath the

world”. One of the first western visitors to the country, the Briton S.

Turner, described the institution as follows: “A sovereign Lama,

immaculate, immortal, omnipresent and omniscient is placed at the summit of

their fabric. [!] He is esteemed the vice regent of the only God, the

mediator between mortals and the Supreme ... He is also the center of all

civil government, which derives from his authority all influence and power”

(quoted by Bishop, 1993, p. 93).

Turner, who knew nothing about the secrets of

Tantrism, saw the Dalai Lama as a kind of bridge (pontifex maximus) between transcendence and reality. He was for

this author the governor for and the image of Buddha, his majesty appeared

as the pale earthly reflection of the deity. This is, however, too modest!

The Dalai Lama does not represent

Buddha on earth, nor is he an intermediary, nor a reflection — he is the

complete deity himself. He is a Kundun,

that is, he is the presence of Buddha, he is a “living Buddha”. For this

reason his power and his compassion are believed to be unbounded. He is

world king and Bodhisattva rolled into one.

The Dalai Lama unites spiritual and worldly power

in one person — a dream which remained unfulfilled for the popes and

emperors of the European Middle Ages. [2] According to doctrine, the Kundun is the visible form (nirmanakaya) of this comprehensive

divine power in time; he exists as the earthly appearance of the time god, Kalachakra; he is the supreme “lord

of the wheel of time”. For this reason he was handed a golden wheel as a

sign of his omnipotence at his enthronement. He is prayed to as the “ruler

of rulers”, the “victor” and the “conqueror”. Even if he himself does not

wield the sword, he can still order others to do so, and oblige them to go

to war for him.

There was just as little distinction between

power-political and religious organization in the Tibet of old as in the

Egypt of the Pharaohs. As such, every action of the Tibetan god-king,

regardless of how mundane it may appear to us, was (and is) religiously

grounded and holy. The monastic state he governs was (and is) considered to

be the earthly reflection of a cosmic realm. In essence there was (and is)

no difference between the supernatural order and the social order. The two

vary only in their degree of perfection, then the ordo universalis (universal order) which is apparent in this

world is marred only by flaws due to the imperfection of humanity (and not

due to any imperfection of the Kundun).

Anarchy, disorder, revolt, famine, disobedience, defeat, expulsion are a

matter of the deficiencies of the age, but never incorrect conduct by the

god-king. He is without blemish and only present in this world in order to

instruct people in the Dharma

(the Buddhist doctrine).

The state as the

microcosmic body of the Dalai Lama

Ashoka, the first Buddhist Emperor, was considered

to be the incarnation of a Bodhisattva and probably as that of a Chakravartin (world ruler). His role

as the highest bearer of state office was, however, not of a tantric

nature. Fundamentally, he acted like every sacred king before him. His

decisions, his edicts, and his deeds were considered holy — but he did not

govern via control of his inner microcosmic energies. The pre-tantric Chakravartin (e.g., Ashoka)

controlled the cosmos, but the tantric world ruler is (e.g., the Dalai

Lama) the cosmos itself. This equation of macrocosmic procedures and

microcosmic events within the mystic body of the tantric hierarch even

includes his people. The tantra master upon the Lion Throne does not just

represent his people, rather — to be precise — he is them. The oft-quoted phrase “I am the state” is literally

true of him.

He controls it — as we have described above- through

his inner breath, through the movement of the ten winds (dasakaro vasi). His two chief

metapolitical activities consist of the rite and the bodily control with

which he secretly steers the cosmos and his kingdom. The political, the

cultic, and his mystic physiology are inseparable for him. In his energy

body he plays out the events virtually, as in a computer, in order to then

allow them to become reality in the world of appearances.

The tantric Buddhocracy is thus an interwoven

total of cosmological, religious, territorial, administrative, economic,

and physiological events. Taking the doctrine literally, we must thus

assume that Tibet, with all its regions, mountains, valleys, rivers, towns,

villages, with its monasteries, civil servants, aristocrats, traders,

farmers, and herdsmen, with all its plants and animals can be found anew in

the energy body of the Dalai Lama. Such for us seemingly fantastic concepts

are not specifically Tibetan. We can also find them in ancient Egypt,

China, India, even in medieval Europe up until the Enlightenment. Thus,

when the Kundun says in 1996 in

an interview that “my proposal treats Tibet as something like one human

body. The whole Tibet is one body”, this is not just intended allegorically

and geopolitically, but also tantrically (Shambhala Sun, archives, November, 1996). Strictly interpreted,

the statement also means: Tibet and my energy body are identical with one

another.

Tibet on the other hand is a microcosmic likeness

of the sum of humanity, at least that is how the Tibetan National Assembly

sees the matter in a letter from the year 1946. We can read there that

“there are many great nations on this earth who have achieved unprecedented

wealth and might, but there is only one nation which is dedicated to the

well-being of humanity and that is the religious land of Tibet, which

cherishes a joint spiritual and temporal system” (Newsgroup 12).

The mandala as the

organizational form of the Tibetan state

There is something specific in the state structure

of the historical Buddhocracy which distinguishes it from the purely

pyramidal constitution of Near Eastern theocracies. Alone because of the

many schools and sub-schools of Tibetan Buddhism we cannot speak of a

classic leadership pyramid at the pinnacle of which the Dalai Lama stands.

In order to describe in general terms the Buddhocratic form of state, S. J.

Tambiah introduced a term which has in the meantime become widespread in

the relevant literature. He calls it “galactic politics” or “mandala

politics” (Tambiah, 1976, pp. 112 ff.) What can be understood by this?

As in a solar system, the chief monasteries of the

Land of Snows orbit like planets around the highest incarnation of Tibet,

the god-king and world ruler from Lhasa, and form with him a living

mandala. This planetary principle is repeated in the organizational form of

the chief monasteries, in the center of which a tulku likewise rules as a

“little” Chakravartin. Here, each

arch-abbot is the sun and father about whom rotate the so-called “child

monasteries”, that is, the monastic communities subordinate to him. Under

certain circumstances these can form a similar pattern with even smaller

units.

Mandala-pattern

of the tibetan government (above) and the corresponding government offices

around the Jokhang-Temple (below) Mandala-pattern

of the tibetan government (above) and the corresponding government offices

around the Jokhang-Temple (below)

A collection of many “solar systems” thus arises

which together form a “galaxy”. Although the Dalai Lama represents an

overarching symbolic field, the individual monasteries still have a wide

ranging autonomy within their own planet. As a consequence, every

monastery, every temple, even every Tulku forms a miniature model of the

whole state. In this idealist conception they are all “little “ copies of

the universal Chakravartin (wheel

turner) and must also behave ideal-typically like him. All the thoughts and

deeds of the world ruler must be repeated by them and ideally there should

be no differences between him and them. Then all the planetary units within

the galactic model are in harmony with one another. In the light of this

idea, the frequent and substantial disagreements within the Tibetan clergy

appear all the more paradox.

Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, forms the cosmic center of

this galaxy. Two magnificent city buildings symbolize the spiritual and

worldly control of the Dalai Lama: The cathedral

(the Jokhang temple) his priesthood; the palace (the Potala) his kingship. The Fifth Dalai Lama ordered

the construction of his residence on the “Red Mountain” (Potala) from where the Tibetan

rulers of the Yarlung dynasty once reigned, but he did not live to see its

magnificent completion. Instead of laying a foundation stone, the god-king

had a stake driven into the soil of the “red mountain” and summoned the

wrathful deities, probably to demonstrate here too his power over the earth

mother, Srinmo, whose nailed down

heart beats beneath the Jokhang.

Significantly, a sanctuary in southern India

dedicated to Avalokiteshvara was

known in earlier times as a “Potala”. His Tibetan residence, which offers a

view over all of Lhasa, was a suitably high place for the “Lord who looks

down from above” (as the name of the Bodhisattva can be translated). The

Potala was also known as the “residence of the gods”.

Tibet is also portrayed in

the geometric form of a Mandala in the religious political literature.

„While it demonstrates hierarchy, power relations, and legal levels”,

writes Rebecca Redwood French, „the Mandala ceaselessly pulsates with

movement up, down and between its different parts” (Redwood French, 1995,

p. 179).

The mchod-yon relationship

to other countries

What form does the relationship of a Chakravartin from the roof of the

world to the rulers of other nations take in the Tibetan way of looking at

things? The Dalai Lama was (and is) — according to doctrine — the highest

(spiritual) instance for all the peoples of the globe. Their relationship

to him are traditionally regulated by what is known as the mchod-yon formula.

With an appeal to the historical Buddha, the

Tibetans interpret the mchod-yon

relation as follows:

- The

sacred monastic community (the sangha)

is far superior to secular ruler.

- The

secular ruler (the king) has the task, indeed the duty, to afford the sangha military protection and

keep it alive with generous “alms”. In the mchod-yon relation “priest” and “patron” thus stood (and

stand) opposed, in that the patron was obliged to fulfill all the

worldly needs of the clergy.

After Buddhism became more and more closely linked

with the idea of the state following the Ashoka period, and the “high

priests” themselves became “patrons” (secular rulers), the mchod-yon relation was applied to

neighboring countries. That is, states which were not yet really subject to

the rule of the priest-king (e.g., of the Dalai Lama) had to grant him military

protection and “alms”. This delicate relation between the Lamaist

Buddhocracy and its neighboring states still plays a significant role in

Chinese-Tibetan politics today, since each of the parties interprets them

differently and thus also derives conflicting rights from it.

The Chinese side has for centuries been of the

opinion that the Buddhist church (and the Dalai Lama) must indeed be paid

for their religious activities with “alms”, but only has limited rights in

worldly matters. The Chinese (especially the communists) thus impose a

clear division between state and church and in this point are largely in

accord with western conceptions, or they with justification appeal to the

traditional Buddhist separation of sangha

(the monastic community) and politics (Klieger, 1991, p. 24). In contrast,

the Tibetans do not just lay claim to complete political authority, they

are also convinced that because of the mchod-yon

relation the Chinese are downright obliged to support them with “alms”

and protect them with “weapons”. Even if such a claim is not articulated in

the current political situation it nonetheless remains an essential

characteristic of Tibetan Buddhocracy. [3]

Christiaan Klieger has convincingly demonstrated

that these days the entire exile Tibetan economy functions according to the

traditional mchod-yon

(priest-patron) principle described above, that is, the community with the

monks at its head is constantly supported by non-Tibetan institutions and

individuals from all over the world with cash, unpaid work, and gifts. The

Tibetan economic system has thus remained “medieval” in emigration as well.

Whether the considerable gifts to the Tibetans in

exile are originally intended for religious or humanitarian projects no

longer plays much of a role in their subsequent allocation. „Funds

generated in the West as part of the religious system of donations,” writes

Klieger, „are consequently transformed into political support for the

Tibetan state” (Klieger, 1991, p. 21). The formula, which proceeds from the connection

between spiritual and secular power, is accordingly as follows: whoever

supports the politics of the exile Tibetans also patronizes Buddhism as

such or, vice versa, whoever wants to foster Buddhism must support Tibetan

politics.

The feigned belief of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama in western

democracy

However authoritarian and undemocratic the guiding

principles of the Buddhist state are, these days (and in total contrast to

this) the Fourteenth Dalai Lama exclusively professes a belief in a western

democratic model. Now, is the Kundun’s

conception of democracy a matter of an seriously intended reform of the old

feudal Tibetan relations, a not yet realized long-term political goal, or

simply a tactical ploy?

Admittedly, since 1961 a kind of parliament exists

among the Tibetans in exile in which the representatives of the various

provinces and the four religious schools hold seats as members. But the

“god-king” still remains the highest government official. According to the

constitution, he cannot be stripped of his authority as head of state and

as the highest political

instance. There has never, Vice President Thubten Lungring has said, been a

majority decision against the Dalai Lama. The latter is said to have with a

smile answered a western journalist who asked him whether it was even

possible that resolutions could be passed against him, “No, not possible”

(Newsgroup 13).

Whenever he is asked about his unshakable office,

the Kundun always repeats that

this absolutist position of power was thrust upon him against his express

wishes. The people emphatically demanded of him that he retain his role as

regent for life. With regard to the charismatic power of integration he is

able to exercise, this was certainly a sensible political decision. But

this means that the exile Tibetan state system still remains Buddhocratic

at heart. Nonetheless, this does not prevent the Kundun from presenting the constitution finally passed in 1963

as being “based upon the principles of modern democracy”, nor from

constantly demanding the separation of church and state (Dalai Lama XIV,

1993b, p. 25; 1996b, p. 30).

In the course of its 35-year existence the exile

Tibetan “parliament” has proved itself to be purely cosmetic. It was barely

capable of functioning and played a completely subordinate role in the

political decision-making process. The “first ever democratic political

party in the history of Tibet” as it terms itself in its political

platform, the National Democratic

Party of Tibet (NDPT), first saw the light of day in the mid nineties.

Up until at least 1996 the “people” were completely uninterested in the

democratic rules of the game (Tibetan

Review, February 1990, p. 15). Politics was at best conducted by

various pressure groups — the divisive regional representations, the

militant Tibetan Youth Association

and the senior abbots of the four chief sects. But ultimately decisions

(still) lay in the hands of His Holiness, several executive bodies, and the

members of three families, of whom the most powerful is that of the Kundun, the so-called “Yabshi clan”.

The same is true of the freedom of the press and

freedom of speech in general. “The historian Wangpo Tethong,” exiled

Tibetan opponents of the Dalai Lama wrote in 1998, “whose noble family has

constantly occupied several posts in the government in exile, equates

democratization in exile with the ‘propagation of an ideology of national

unity’ and 'religious and political unification'. This contradicts the

western conception of democracy” (Press release of the Dorje Shugden

International Coalition, February 7, 1998; translation). The sole (!)

independent newspaper in Dharamsala, with the name of Democracy (in Tibetan: Mangtso),

was forced to cease publication under pressure from members of the

government in exile. In the Tibet

News, an article by Jamyang Norbu on the state of freedom of the press

is said to have appeared. The author summarizes his analysis as follows:

“Not only is there no encouragement or support for a free Tibetan press,

rather there is almost an extinguishing of the freedom of opinion in the

Tibetan exile community” (Press release of the Dorje Shugden International

Coalition, February, 7, 1998).

The Tibetan parliament in exile and the democracy

of the exiled Tibetans is a farce. Even Thubten J. Norbu, one of the Dalai

Lama’s brothers, is convinced of this. When in the early nineties he

clashed fiercely with Gyalo Thondop, another brother of the Kundun, over the question of foreign

affairs, the business of government was paralyzed due to this dispute

between the brothers (Tibetan Review,

September 1992, p. 7). The 11th

parliamentary assembly (1991), for instance, could not reach consensus over

the election of a full cabinet. The parliamentary members therefore

requested that His Holiness make the decision. The result was that of seven

ministers, two belonged to the “Yabshi clan”, that is, to the Kundun’s own family: Gyalo Thondop

was appointed chairman of the council of ministers and was also responsible

for the “security” department. The Dalai Lama’s sister, Jetsun Pema, was

entrusted with the ministry of education.

In future, everything is supposed to change.

Nepotism, corruption, undemocratic decisions, suppression of the freedom of

the press are no longer supposed to exist in the new Tibet. On June 15,

1988, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama announced to the European Parliament in

Strasbourg that upon his return a constitutional assembly would be formed

in the Land of Snows, headed by a president who would possess the same

authority as he himself now enjoyed. Following this there would be

democratic elections. A separation of church and state along western lines

would be guaranteed from the outset in Tibet. There would also be a

voluntary relinquishment of some political authority vis-à-vis the Chinese.

He,

the Dalai Lama, would recognize the diplomatic and military supremacy of

China and be content with just the „fields of religion, commerce,

education, culture, tourism, science, sports, and other non-political

activities” (Grunfeld, 1996, p. 234).

But despite such spoken professions, the national

symbols tell another tale: With pride, every Tibetan in exile explains that

the two snow lions on the national flag signify the union of spiritual and

worldly power. The Tibetan flag is thus a visible demonstration of the

Tibetan Buddhocracy. Incidentally, a Chinese yin yang symbol can be found in the middle. This can hardly be a

reference to a royal couple, and rather, is clearly a symbol of the

androgyny of the Dalai Lama as the highest tantric ruler of the Land of

Snows. All the other heraldic features of the flag (the colors, the flaming

jewels, the twelve rays, etc.), which is paraded as the coat of arm of a

democratic, national Tibet, are drawn from the royalist repertoire of the

Lamaist priesthood.

The Strasbourg

Declaration of 1989 and the renunciation of autonomy it contains are

sharply criticized by the Tibetan

Youth Congress (TYC), the European

Tibetan Youth Association, and the Dalai Lama’s elder brother, Thubten

Norbu. When the head of the Tibetan

Youth Congress came under strong attack because he did not approve of

the political decisions of the Kundun,

he defended himself by pointing out that the Dalai Lama himself had called

upon him to pursue this hard-line stance — probably so as to have the

possibility of distancing himself from his Strasbourg Declaration (Goldstein, 1997, p. 139).

This political double game is currently

intensifying. Whilst the god-king continues to extend his contacts with

Beijing, the TYC’s behavior is increasingly vocally radical. We have become

too nonviolent, too passive, declared the president of the organization,

Tseten Norbu, in 1998 (Reuters, Beijing, June 22, 1998). In the

countermove, since Clinton’s visit to China (in July 1998) the Dalai Lama

has been offering himself to the Chinese as a peacemaker to be employed

against his own people as the sole bulwark against a dangerous Tibetan

radicalism: “The resentment in Tibet against the Chinese is very strong.

But there is one [person] who can influence and represent the Tibetan

people [he means himself here]. If he no longer existed the problem could

be radicalized” he threatened the Chinese leadership, of whom it has been

said that they want to wait out his death in exile (Time, July 13, 1998, p. 26).

Whatever happens to the Tibetan people in the

future, the Dalai Lama remains a powerful ancient archetype in his double

function as political and spiritual leader. In the moment in which he has

to surrender this dual role, the idea, anchored in the Kalachakra Tantra, of a “world king” first loses its visible

secular part, then the Chakravartin

is worldly and spiritual ruler at once. In this case the Dalai Lama would

exercise a purely spiritual office, which more or less corresponds to that

of a Catholic Pope.

How the Kundun

will in the coming years manage the complicated balancing act between

religious community and nationalism, democracy and Buddhocracy, world

dominion and parliamentary government, priesthood and kingship, is a

completely open question. He will at any rate — as Tibetan history and his

previous incarnations have taught us — tactically

orient himself to the particular political constellations of power.

The democratic faction

Within the Tibetan community there are a few

exiled Tibetans brought up in western cultures who have carefully begun to

examine the ostensible democracy of Dharamsala. In a letter to the Tibetan Review for example, one

Lobsang Tsering wrote: „The Tibetan society in its 33-years of exile has

witnessed many scandals and turmoils. But do the people know all the

details about these events? ... The latest scandal has been the 'Yabshi vs.

Yabshi' affair concerning the two older brothers of the Dalai Lama. [Yabshi is the family name of the

Dalai Lama’s relatives.] The rumours keep on rolling and spreading like

wildfire. Many still are not sure exactly what the affair is all about. Who

are to blame for this lack of information? Up till now. anything

controversial has been kept as a state secret by our government. It is true

that not every government policy should be conducted in the open. However,

in our case, nothing is done in the open” (Tibetan Review, September 1992, p. 22). [4]

We should also take seriously the liberal

democratic intentions of younger Tibetans in the homeland. For instance,

the so-called Drepung Manifesto, which appeared in 1988 in Lhasa, makes a

refreshingly critical impression, although formulated by monks: „Having completely

eradicated the practices of the old society with all its faults,” it says

there. „the future Tibet will not resemble our former condition and be a

restoration of serfdom or be like the so-called ‘old system’ of rule a

succession of feudal masters or monastic estates.” (Schwartz, 1994, p.

127). Whether such

statements are really intended seriously is something about which one can

only speculate. The democratic reality among the Tibetans in exile gives

rise to some doubts about this.

It is likewise a fact that the protest movement in

Tibet, continually expanding since the eighties, draws together everyone

who is dissatisfied in some way, from upright democrats to the dark

monastic ritualists for whom any means is acceptable in the quest to restore

through magic the power of the Dalai Lama on the “roof of the world”. We

shall return to discuss several examples of this in our chapter War and Peace. Western tourists who

are far more interested in the occult and mystic currents of the country

than in the establishment of a “western” democracy, encourage such atavisms

as best they can.

For the Tibetan within and outside of their

country, the situation is extremely complicated. They are confronted daily

with professions of faith in western democracy on the one hand and a

Buddhocratic, archaic reality on the other and are supposed to (the Kundun imagines) decide in favor of

two social systems at once which are not compatible with one another. In

connection with the still to be described Shugden affair this contradiction has become highly visible and

self-evident.

Additionally, the Tibetans are only now in the

process of establishing themselves as a nation, a self-concept which did

not exist at all before — at least since the country has been under

clerical control. We have to refer to the Tibet of the past as a cultural community and not as a nation. It was precisely Lamaism and

the predecessors of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, who now sets himself at the

forefront of the Tibetan Nation,

who prevented the development of a real feeling of national identity among

the populace. The “yellow church” advocated their Buddhist teachings,

invoked their deities and pursued their economic interests — yet not those

of the Tibetans as a united people. For this reason the clergy also never

had the slightest qualms about allying themselves with the Mongolians or

the Chinese against the inhabitants of the Land of Snows.

The “Great Fifth”: Absolute Sun King of Tibet

Historians are unanimous in maintaining that the

Tibetan state was the ingenious construction of a single individual. The

golden age of Lamaism begins with Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso, the Fifth Dalai

Lama (1617–1682) and also ends with him. The saying of the famous

historian, Thomas Carlyle, that the history of the world is nothing other

than the biography of great men may be especially true of him. None of his

successors have ever achieved the same power and visionary force as the

“Great Fifth”. They are in fact just the weak transmission of a very

special energy which was gathered together in his person in the seventeenth

century. The spiritual and material foundations which he laid have shaped

the image of Tibet in both East and West up until the present day. But his practical political power, limited firstly by various Buddhist school and

then also by the Mongolians and Chinese, was not at all so huge. Rather, he

achieved his transtemporal authority through the adroit accumulation of all

spiritual resources and energies,

which he put to service with an admirable lack of inhibition and an

unbounded inventiveness. With cunning and with violence, kindness and

brutality, with an enthusiasm for ostentatious magnificence, and with magic

he organized all the significant religious forms of expression of his

country about himself as the shining center. Unscrupulous and flexible,

domineering and adroit, intolerant and diplomatic, he carried through his

goals. He was statesman, priest, historian, grammarian, poet, painter,

architect, lover, prophet, and black magician in one — and all of this

together in an outstanding and extremely effective manner.

The grand

siècle of the “Great Fifth” shone out at the same period in time as

that of Louis XIV (1638–1715), the French sun king, and the two monarchs

have often been compared to one another. They are united in their iron will

to centralize, their fascination for courtly ritual, their constant

exchange with the myths, and much more besides. The Fifth Dalai Lama and

Louis XIV thought and acted as expressions of the same temporal current and

in this lay the secret of their success, which far exceeded their practical

political victories. If it was the concept of the seventeenth century to

concentrate the state in a single person, then for both potentates the

saying rings true: l'état c'est moi

("I am the state”). Both lived from the same divine energy, the

all-powerful sun. The “king” from Lhasa also saw himself as a solar “fire

god”, as the lord of his era, an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara. The year of his birth (1617) is assigned to

the “fire serpent” in the Tibetan calendar. Was this perhaps a cosmic

indicator that he would become a master of high tantric practices, who

governed his empire with the help of the kundalini ("fire serpent”)?

In the numerous visions of the potentate in which

the most important gods and goddesses of Vajrayana appeared before him, tantric unions constantly took

place. For him, the transformation of sexuality into spiritual and worldly

power was an outright element of his political program. Texts which he

himself wrote describe how he, absorbed by one such exercise by a divine

couple, slipped into the vagina of his wisdom consort, bathed there “in the

red and white bodhicitta” and

afterwards returned to his old body blissful and regenerated (Karmay, 1988,

p. 49).

Contemporary documents revere him as the “sun and

moon” in one person. (Yumiko, 1993, p. 41). He had mastered a great number

of tantric techniques and even practiced his ritual self-destruction (chod) without batting an eyelid.

Once he saw how a gigantic scorpion penetrated into his body and devoured

all his internal organs. Then the creature burst into flames which consumed

the remainder of his body (Karmay, 1988, p. 52). He exhibited an especial

predilection for the most varied terror deities who supported him in

executing his power politics.

The Fifth Dalai Lama was obsessed by the deliriums

of magic. He saw all of his political and cultural successes as the result

of his own invocations. For him, armies were only the executive organs of

prior tantric rituals. Everywhere, he — the god upon the Lion Throne —

perceived gods and demons to be at work, with whom he formed alliances or

against whom he took to the field. Every step that he took was prepared for

by prophecies and oracles. The visions in which Avalokiteshvara appeared to him were frequent, and just as

frequently he identified with the “fire god”. With a grand gesture he

dissolved the whole world into energy fields which he attempted to control

magically — and he in fact succeeded. The Asia of the time took him

seriously and allowed him to impose his system. He reigned as Chakravartin, as world ruler, and as

the Adi Buddha on earth. Chinese Emperors and Mongolian Khans feared

him for his metaphysical power.

One might think that his religious emotionalism

was only a pretext, to be employed as a means of establishing real power.

His sometimes sarcastic, but always sophisticated manner may suggest this.

It is, however, highly unlikely, then the divine statesman had his occult

and liturgical secrets written down, and it is clear from these records

that his first priority was the control of the symbolic world and the

tantric rituals and that he derived his political decisions from these.

His Secret

Biography and the Golden

Manuscript which he wrote (Karmay, 1988) were up until most recently

kept locked away and were only accessible to a handful of superiors from

the Gelugpa order. These two documents — which may now be viewed– also

reveal the author to be a grand sorcerer who evaluated anything and everything

as the expression of divine plans and whose conceptions of power are no

longer to be interpreted as secular. There is no doubting that the “Great

Fifth” thought and acted as a deity completely consciously. This sort of

thing is said to be frequent among kings, but the lord from the roof of the

world also possessed the energy and the power of conviction to transform

his tantric visions into a reality which still persists today.

The predecessors of the Fifth Dalai Lama

The organizational and disciplinary strength of

the Gelugpa ("Yellow Hat”) order formed the Fifth Dalai Lama’s power

base, upon which he could build his system. Shortly after the death of

Tsongkhapa (the founder of the “Yellow Hats”) his successors adopted the

doctrine of incarnation from the Kagyupa sect. Hence the chain of

incarnated forebears of the “Great Fifth” was fixed from the start. It

includes four incarnations from the ranks of the Gelugpas, of whom only the

last two bore the title of Dalai Lama,

the first pair were accorded the rank posthumously.

The chain begins with Gyalwa Gendun Drub

(1391–1474) , a pupil of Tsongkhapa and later the First Dalai Lama. He was

an outstanding expert on, and higher initiand into, the Kalachakra Tantra and composed several

commentaries upon it which are still read today. His writings on this

topic, even if they never attain the methodical precision and canonical

knowledge of his teacher, Tsongkhapa, show that he practiced the tantra and

sought bisexuality in “the form of Kalachakra

and his consort” (Dalai Lama I, 1985, p. 181).

His androgynous longings are especially clear in

the hymns with which he invoked the goddess Tara so as to be able to assume her feminine form: “Suddenly I

appear as the holy Arya Tara, whose mind is beyond samsara” he writes. “My

body is green in color and my face reflects a warmly serene smile ...

attained to immortality, my appearance is that of a sixteen-year-old-girl”

(Dalai Lama I, 1985, pp. 135, 138).

This appearance as the goddess of mercy did not,

however, restrain him from following a pretty hard line in the construction

of the legal system. He determined that prisons be constructed in all

monasteries, where some of his opponents lost their lives under inhuman

circumstances. The penal system which he codified was intransigent and

cruel. Days without food and whippings were a part of this, just like the

cutting off of the right hand in cases of theft or the death penalty for

breach of the vows of celibacy, insofar as this took place outside of the

tantric rituals. His severity and rigor nonetheless earned him the sympathy

of the people, who saw him as the arm of a just and angry god who brought

order to the completely deteriorated world of the monastic clergy.

The title Dalai

Lama first appears during the encounter between the arch-abbot of Sera,

Sonam Gyatso (1543–1588) and the

Mongolian Khan, Altan. The prince of the church (later the Third Dalai

Lama) undertook the strenuous journey to the north and visited the Mongols

in the year 1578 at their invitation. He spent a number of days at the

court of Altan Khan, initiated him into the teachings of the Buddha a and

successfully demonstrated his spiritual power through all manner of

sensational miracles. One day the prince of the steppes appeared in a white

robe which was supposed to symbolize love, and confessed with much feeling

to the Buddhist faith. He promised to transform the “blood sea” into a “sea

of milk” by changing the Mongolian laws. Sonam Gyatso replied, “You are the

thousand-golden-wheel-turning Chakravartin

or world ruler” (Bleichsteiner, 1937, p. 89).

It can be clearly gathered from this apotheosis

that the monk conceded secular authority to the successor of Genghis Khan.

But as an incarnated Buddha he ranked himself more highly. This emerges

from an initiatory speech in which one of Altan's nephews compares him to

the moon, but addresses the High Lama from the Land of Snows as the

omnipotent sun (Bleichsteiner, 1937, p. 88). But the Mongol prince called

his guest “Dalai Lama”, a somewhat modest title on the basis of the

translation usual these days, “Ocean of Wisdom”. Robert Bleichsteiner also

translates it somewhat more emotionally as “Thunderbolt-bearing World Ocean

Priest”. The god-king of Tibet thus bears a Mongolian title, not a Tibetan

one.

At the meeting between Sonam Gyatso and Altan Khan

there were surely negotiations about the pending fourth incarnation of the

“Dalai Lama” (Yonten Gyatso 1589–1617), then he appeared among the Mongols

in the figure of a great-grandchild of Khan’s. Bleichsteiner refers to this

“incarnation decision” as a “particularly clever chess move”, which finally

ensured the control of the “Yellow Hats” over Mongolia and obliged the

Khans to provide help to the order (Bleichsteiner, 1937, p. 89). The

Mongolian Fourth Dalai Lama died at the age of 28 and did not play a

significant political role.

This was taken over by the powerful Kagyupa sect

(the so-called “Red Hats”) at this stage in time. The “Red Hats” recruited

their members exclusively from national (Tibetan) forces. They had attacked

Sonam Gyatso’s (the III Dalai Lama’s) journey to the Mongols as treason and

were able to continually expand their power political successes so that by

the 1630s the Gelugpa order was only savable via external intervention.

Thus, nothing seemed more obvious than that the

“Great Fifth” should demonstratively adopt the Mongolian title “Dalai Lama”

so as to motivate the warlike nomadic tribes from the north to occupy and

conquer Tibet. This state political calculation paid off in full. The

result was a terrible civil war between the Kagyupas and the followers of

the prince of Tsang on the one side and the Gelugpas and the Mongol leader

Gushri Khan on the other.

If the records are to be trusted, the Mongol

prince, Gushri Khan, made a gift of his military conquests (i.e., Tibet) to

the Fifth Dalai Lama and handed over his sword after the victory over the

“Red Hats”. This was not evaluated symbolically as a pacifist act, but

rather as the ceremonial equipping of the prince of the church with secular

power. Yet it remains open to question whether the power-conscious Mongol

really saw this symbolic act in these terms, then de jure Gushri Khan retained the title “King of Tibet” for

himself. The “Great Fifth” in contrast, certainly interpreted the gift of

the sword as a gesture of submission by the Khan (the renunciation of

authority over Tibet), then de facto

from now on he managed affairs like an absolute ruler.

The Secret Biography

The Fifth Dalai Lama took his self-elevation to

the status of a deity and his magic practices just as seriously as he did

his real power politics. For him, every political act, every military

operation was launched by a visionary event or prepared for with a

invocatory ritual. Nevertheless, as a Tantric, the dogma of the emptiness

of all being and the nonexistence of the phenomenal world stood for him

behind the whole ritual and mystic theater which he performed. This was the

epistemological precondition to being able to control the protagonists of

history just like those of the spiritual world. It is against this

framework that the “Great Fifth” introduces his autobiography (Secret Biography) with an irony which undermines his own life’s work

in the following verses:

The erudite should not

read this work, they will be embarrassed.

It is only for the

guidance of fools who revel in fanciful ideas.

Although it tries frankly

to avoid pretentiousness,

It is nevertheless

corrupted with deceit.

By speaking honestly on whatever

occurred, this could be taken to be lies.

As if illusions of

Samsara were not enough,

This stupid mind of mine

is further attracted

To ultra-illusory

visions.

It is surely mad to say

that the image of the Buddha's compassion

Is reflected in the mirror

of karmic existence.

Let me now write the

following pages,

Though it will disappoint

those who are led to believe

That the desert-mirage is

water,

As well as those who are

enchanted by folk-tales,

And those who delight in

red clouds in summer.”

(Karmay, 1988, p. 27)

Up until recent times the Secret Biography had not been made public, it was a secret

document only accessible to a few chosen. There is no doubting that the

power-obsessed “god-king” wanted to protect the extremely intimate and

magic character of his writings through the all-dispersing introductory

poem. One of the few handwritten copies is kept in the Munich State

Library. There it can be seen that the Great Fifth nonetheless took his

“fairy tales” so seriously that he marked the individual chapters with a

red thumbprint.

Everything about Tibet which so fascinates people

from the West is in collected in the multilayered character of the Fifth

Dalai Lama. Holiness and barbarism, compassion and realpolitik, magic and power, king and mendicant monk, splendor

and modesty, war and peace, megalomania and humility, god and mortal — the

pontiff from Lhasa was able to simplify these paradoxes to a single formula

and that was himself. He was for an ordinary person one of the

incomprehensibly great, a contradiction made flesh, a great solitary, upon

whom in his own belief the life of the world hung. He was a mystery for the

people, a monster for his enemies, a deity for his followers, a beast for

his opponents. This ingenious despot is — as we shall later see — the

highest example for the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama.

The regent Sangye Gyatso

The Fifth Dalai Lama did not need to worry about a

successor, because he was convinced that he would be reincarnated in a

child a few days after his death. Yet with wise foresight the time between

his rebirth and his coming of age needed to be organized. Here too, the

“Great Fifth”'s choice was a brilliant piece of power politics. As „regent” he

decided to appoint the lama Sangye Gyatso (1653–1705) and equipped him with

all the regalia of a king already in the last years of his life. He seated

him upon the broad throne of the fearless lion as the executor of two

duties, one worldly and one religious, which are appropriate to a great Chakravartin kingship, as a lord of

heaven and earth (Ahmad, 1970, p. 43). The Dalai Lama thus appointed him world ruler

until his successor (who he himself was) came of age. It was rumored with

some justification that the regent was his biological son (Hoffmann, 1956,

p. 176).

In terms of his abilities, Sangye Gyatso must be

regarded not just as a skilled statesman, rather he was also the author of

a number of intelligent books on such varied topics as healing, law,

history, and ritual systems. He proceeded against the women of Lhasa with

great intolerance. According to a contemporary report he is said to have

issued a command that every female being could only venture into public

with a blackened face, so that the monks would not fall into temptation.

So as to consolidate his threatened position

during the troubled times, he kept the demise of his “divine father” (the

Fifth Dalai Lama) secret for ten years and explained that the prince of the

church remained in the deepest meditation. When in the year 1703 the

Mongolian prince, Lhazang, posed the never completely resolved question of

power between Lhasa and the warrior nomads and himself claimed regency over

Tibet, an armed conflict arose.

The right wing of the Mongol army was under the

command of the martial wife of the prince, Tsering Tashi. She succeeded in

capturing the regent and carried out his death sentence personally. If she

was a vengeant incarnation of Srinmo

in the “land of the gods”, then her revenge also extended to the coming

Sixth Dalai Lama, over whose fate we report in a chapter of its own.

The successors of the “Great Fifth”: The Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Dalai Lamas

The Seventh and Eighth Dalai Lamas only played a

minor role in the wider political world. As we have already reported, the

four following god-kings (The Ninth to the Twelfth Dalai Lamas) either died

an early death or were murdered. It was first the so-called “Great

Thirteenth” who could be described as a “politician” again. Although in

constant contact with the modern world, Thubten Gyatso, the Thirteenth

Dalai Lama (1874–1933), thought and acted like his predecessor, the “Great

Fifth”. Visions and magic continued to determine political thought and

activity in Tibet after the boy moved into the Potala amid great spectacle

in July 1879. In 1894 he took power over the state. Shortly before, the

officiating regent had been condemned because of a black magic ritual which

he was supposed to have performed to attack the young thirteenth god-king,

and because of a conspiracy with the Chinese. He was thrown into one of the

dreadful monastery dungeons, chained up, and maltreated him till he died. A

co-conspirator, head of a distinguished noble family, was brought to the

Potala after his deeds were discovered and pushed from the highest

battlements of the palace. His names, possessions and even the women of his

house were then given to a favorite of the Dalai Lama’s as a gift.

In 1904 the god-king had to flee to Mongolia to

evade the English who occupied Lhasa. Under pressure from the Manchu

dynasty he visited Beijing in 1908. We have already described how the

Chinese Emperor and the Empress Dowager Ci Xi died mysteriously during this

visit. He later fell out with the Thirteenth Dalai Lama with the Panchen

Lama,[5] who cooperated with the

Chinese and was forced to flee Tibet in 1923. The “Great Thirteenth”

conducted quite unproductive fluctuating political negotiations with

Russia, England, and China; why he was given the epithet of “the Great”

nobody really knows, not even his successor from Dharamsala.

An American envoy gained

the impression that His Holiness (the Thirteenth Dalai Lama) „cared very

little, if at all, for anything which did not affect his personal

privileges and prerogatives, that he separated entirely his case from that

of the people of Tibetan, which he was willing to abandon entirely to the

mercy of China” (Mehra, 1976, p.20) When we recall that the institution of the Dalai

Lama was a Mongolian arrangement which was put through in the civil war of

1642 against the will of the majority of the Tibetans, such an evaluation

may well be justified.

As an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara, the thirteenth hierarch also (like the “Great

Fifth”) saw himself surrounded less by politicians and heads of state than

by gods and demons. David Seyfort Ruegg most astutely indicates that the

criteria by which Buddhists in positions of power assess historical events

and personalities have nothing in common with our western, rational

conceptions. For them, “supernatural” forces and powers are primarily at

work, using people as bodily vessels and instruments. We have already had a

taste of this in the opposition between the god-king as an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara and Guanyin in the form of the Empress

Dowager Ci Xi. Further examples in the coming chapters should show how

magic and politics, war and ritual are also interwoven here.

Now what is the situation with regard to these

topics and the living Fourteenth Dalai Lama? Has his almost 40--year

exposure to western culture changed anything fundamental in the traditional

political understanding? Is the current god-king free of the ancient,

magical visions of power of his predecessors? Let us allow him to answer

this question himself: in adopting the position of the Fifth Dalai Lama,

the Kundun explained in an

interview in 1997, “I am supposed to follow what he did” (Dalai Lama, HPI

006). As a consequence we too are entitled to accredit the Fourteenth Dalai

Lama with all the deeds and visions of the great fifth hierarch and to

assess his politics according to the criteria of his famous exemplar.

Incarnation and power

Lamaism’s particular brand of controlling power is

based upon the doctrine of incarnation. Formerly (before the Communist

invasion) the incarnation system covered the entire Land of Snows like a

network. In Tibet, the monastic incarnations are called “tulkus”. Tulku

means literally the “self-transforming body”. In Mongolia they are known as

“chubilganes”. There were over a hundred of these at the end of the

nineteenth century. Even in Beijing during the reign of the imperial

Manchus there were fourteen offices of state which were reserved for

Lamaist tulkus but not always occupied.

The Tibetan doctrine incarnation is often

misunderstood. Whilst concepts of rebirth in the West are dominated by a

purely individualist idea in the sense that an individual progresses

through a number of lifetimes on earth in a row, a distinction is drawn in

Tibet between three types of incarnation:

- When

the incarnation as the emanation of a supernatural being, a Buddha,

Bodhisattva, or a wrathful deity. Here, incarnation means that the

lama in question is the embodiment of a deity, just as the Dalai Lama

is an embodiment of Avalokiteshvara.

The tulku lives from the spiritual energies of a transcendent being

or, vice versa, this being emanates in a human body.

- When

reincarnation arises through the initiatory transfer from the master

to the sadhaka, that is, the “root guru” (represented by the master)

and the deities who stand behind him embody themselves in his pupil.

- When

it concerns the rebirth of a historical figure who reveals himself in

the form of a new born baby. For example, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama is

also an incarnation of the Fifth Dalai Lama.

The first and third concepts of incarnation do not

necessarily contradict one another, rather they can complement each other,

so that a person who has already died and deity can simultaneously be

embodied in a person. But come what may, the deity has priority and supreme

authority. It seems obvious that their bodily continuity and presence in

this world is far better ensured by the doctrine of incarnation than by a

natural line of inheritance. In a religious system in which the person

means ultimately nothing, but the gods who stand behind him are everything,

the human body only represents the instrument through which a higher being

can make an appearance. From the deity’s point of view a natural

reproduction would bring the personal interests of a family into conflict

with his or her own divine ambitions.

The incarnation system in contrast is impersonal,

anti-genetic, and anti-aristocratic. For this reason the monastic orders as

such are protected. through the rearing of a “divine” child it creates for itself the best conditions

for the survival of its tradition, which can no longer be damaged by

incapable heirs, family intrigues, and nepotism.

On a more fundamental symbolic level, the doctrine

of incarnation must nevertheless be seen as an ingenious chess move against

the woman’s monopoly on childbirth and the dependence of humanity upon the

cycle of birth. It makes things “theoretically” independent of birth and

the woman as the Great Mother. That mothers are nonetheless needed to bring

the little tulkus into the world is not significant from a Buddhological

point of view. The women serve purely as a tool, they are so to speak the

corporeal cradle into which the god settles down in the form of an embryo.

The conception of an incarnated lama (tulku)

is thus always regarded as a supernatural procedure and it does not arise

through the admixture of the male and female seed as is normal. Like in the

Buddha legend, where the mother of the Sublime One is made pregnant in a

dream by an elephant, so too the mother of a Tibetan tulku has visions and

dreams of divine entities who enter into her. But the role of the “wet

nurse” is taken over by the monks already, so that the child can be suckled

upon the milk of their androcentric wisdom from the most tender age.

The doctrine of reincarnation was fitted out by

the clergy with a high grade symbolic system which cannot be accessed by

ordinary mortals. But as historical examples show, the advantages of the

doctrine were thoroughly capable of being combined now and again with the

principle of biological descent. Hence, among the powerful Sakyapas, where

the office of abbot was inherited within a family dynasty, both the chain

of inheritance and the precepts of incarnation were observed. Relatives,

usually the nephews of the heads of the Sakyapa order, were simply declared

to be tulkus.

Let us consider the Lamaist “lineage tree” or

“spiritual tree” and its relation to the tulku system. Actually, one would

assume that the child recognized as being a reincarnation would already

possess all the initiation mysteries which it had acquired in former lives.

Paradoxically, this is however not the case. Every Dalai Lama, every

Karmapa, every tulku is initiated “anew” into the various tantric mysteries

by a master. Only after this may he consider himself a branch of the

“lineage tree” whose roots, trunk, and crown consist of the many

predecessors of his guru and his guru’s guru. There are critics of the

system who therefore claim with some justification that a child recognized

as an incarnation first becomes the “vessel” of a deity after his

“indoctrination” (i.e., after his initiation).

The traditional power of the individual Lamaist

sects is primarily demonstrated by their lineage tree. It is the idealized

image of a hierarchic/sacred social structure which draws its legitimation

from the divine mysteries, and is supposed to imply to the subjects that

the power elite represent the visible and time transcending assembly of an

invisible, unchanging meta-order. At the origin of the initiation tree

there is always a Buddha who emanates in a Bodhisattva who then embodies

himself in a Maha Siddha. The

roaming, wild-looking founding yogis (the Maha Siddhas) are, however, very soon replaced in the

generations which follow by faceless “civil servants” within the lineage

tree; fantastic great sorcerers have become uniformed state officials. The

lineage tree now consists of the scholars and arch-abbots of the lama

state.

The “Great Fifth” and the system of incarnation

Historically, for the “yellow sect” (the Gelugpa

order) which traditionally furnishes the Dalai Lama, the question of

incarnation at first did not play such a significant role as it did, for

example, among the “Red Hats” (Kagyupa). The Fifth Dalai Lama first

extended the system properly for his institution and developed it into an

ingenious political artifact, whose individual phases of establishment over

the years 1642 to 1653 we can reconstruct exactly on the basis of the

documentary evidence. The “Great Fifth” saw himself as an incarnation of

the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

The embodiment of the Tibetan “national god” was until then a privilege

claimed primarily by the Sakyapa and Kagyupa orders but not by the Gelugpa

school. Rather, their founder, Tsongkhapa, was considered to be an

emanation of the Bodhisattva Manjushri,

the “Lord of Transcendental Knowledge”. In contrast, already in the

thirteenth century the Karmapas presented themselves to the public as

manifestations of Avalokiteshvara.

An identification with the Tibetan “national god”

and first father, Chenrezi (Avalokiteshvara), was, so to speak,

a mythological precondition for being able to rule the Land of Snows and

its spirits, above all since the subjugation and civilization of Tibet were

associated with the “good deeds” of the Bodhisattva, beginning with his

compassionate, monkey union with the primal mother Srinmo. Among the people too, the Bodhisattva enjoyed the

highest divine authority, and his mantra, om mani padme hum, was recited daily by all. Hence, whoever

wished to rule the Tibetans and govern the universe from the roof of the

world, could only do so as a manifestation of the fire god, Chenrezi, the controller of our age.

The “Great Fifth” was well aware of this, and via

a sophisticated masterpiece of the manipulation of metaphysical history, he

succeeded in establishing himself as Avalokiteshvara

and as the final station of a total of 57 previous incarnations of the god.

Or was it — as he himself reported — really a miracle which handed him the

politically momentous incarnation list? Through a terma (i.e., a rediscovered text written and hidden in the era

of the Tibetan kings) which he found in person, his chain of incarnations

was apparently “revealed” to him.

Among the “forebears” listed in it many of the

great figures of Tibetan history can be found — outstanding politicians,

ingenious scholars, master magicians, and victorious military leaders. With

this “discovered” or “concocted” document of his, the “Great Fifth” could

thus shore himself up with a political and intellectual authority which

stretched over centuries. The list was an especially valuable legitimation

for his sacred/worldly kingship, since the great emperor, Songtsen Gampo,

was included among his “incarnation ancestors”. In his analysis of the introduction

of the Chenrezi cult by His

Holiness, the Japanese Tibetologist, Ishihama Yumiko, leaves no doubt that

we are dealing with a power-political construction (Yumiko, 1993, pp. 54,

55).

Now, which entities were — and, according to the

Fifth Dalai Lama’s theory of incarnation, still are — seated upon the

golden Lion Throne? First of all, the fiery Bodhisattva, Avalokiteshvara, then the

androgynous time turner, Kalachakra,

then the Tibetan warrior king, Songtsen

Gampo, then the Siddha versed in magic, Padmasambhava (the founder of Tantric Buddhism in Tibet), and

finally the Fifth Dalai Lama himself with all his family forebears. This

wasn’t nearly all, but those mentioned are the chief protagonists, who

determine the incarnation theater in Tibet. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama, as

the successor of the “Great Fifth” also represents the above-mentioned

“divinities” and historical predecessors.

In an assessment of the Buddhocratic system and

the history of Tibet, the power-political intentions of the two main gods (Avalokiteshvara and Kalachakra) must therefore be

examined and evaluated in the first place so as to deduce the intentions of

the currently living Dalai Lama on this basis. “It is impossible”, the Tibetologist

David Seyfort Ruegg writes, “to draw a clear border between the 'holy and

the 'profane', or rather between the spiritual and the temporal. This is

most apparent in the case of the Bodhisattva kings who are represented by

the Dalai Lamas, since these are both embodiments of Avalokiteshvara ... and worldly rulers” (Seyfort Ruegg, 1995,

p. 91).

If we assume that the higher the standing of a

spiritual entity, the greater his power is, we must pose the question of

why in the year 1650 the Fifth Dalai Lama confirmed and proclaimed the

first Panchen Lama, Lobsang Chokyi Gyaltsen (1567–1662), his former

teacher, as a incarnation of Amitabha.

For indeed, Amitabha, the “Buddha

of unending light”, is ranked higher in the hierarchy than the Bodhisattva

who emanates from him, Avalokiteshvara.

This decision by the extremely power conscious god-king from Lhasa can thus

only be understood when one knows that, as a meditation Buddha, Amitabha may not interfere in

worldly affairs. According to doctrine, he exists only as a principle of

immobility and is active solely through his emanations. Even though he is

the Buddha of our age, he must nevertheless leave all worldly matters to

his active arm, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Through such a division of responsibilities, a contest between the Panchen

Lama and Dalai Lama could never even arise.

Nevertheless, the Panchen Lamas have never wanted

to fall into line with the nonpolitical role assigned to them. In contrast

— they have attempted by all available means to interfere in the “events of

the world”. Their central monastery, Tashi Lhunpo, became at times a

stronghold in which all those foreign potentates who had been rebuffed by

the Potala found a sympathetic ear. While negotiations were conducted with

the Russians and Mongolians in Lhasa at the start of last century, Tashi

Lhunpo conspired with the English and Chinese. Thus, the statesmanly

autonomy of the Panchen Lama has often been the cause of numerous and acrid

discordances with the Dalai Lama which have on several occasions bordered

on a schism.

The sacred power of the Tibetan kings and its conferral upon

the Dalai Lamas

So as to legitimate his full worldly control, it

seemed obvious for the “Great Fifth” to make borrowings from the symbolism

of sacred kingship. The most effective of these was to present himself as

the incarnation of significant secular rulers with the stated aim of now

continuing their successful politics. The Fifth Dalai Lama latched onto

this idea and extended his chain of incarnations to reach the divine first

kings from prehistoric times.

But, as we know, these were in no sense Buddhist,

but rather fostered a singular, shamanist-influenced style of religion.

They traced their origins to an old lineage of spirits who had descended to

earth from the heavenly regions. Through an edict of the Fifth Dalai Lama

they, and with them the later historical kings, were reinterpreted as

emanations from “Buddha fields”. As proof of this, alongside a document

“discovered” by the resourceful hierarch, a further “hidden” text (terma), the Mani Kabum, is cited, which an eager monk is supposed to have

found in the 12th century. In it the three post powerful ruling figures of

the Yarlung dynasty are explained to be emanations of Bodhisattvas:

Songtsen Gampo (617–650) as an embodiment of Avalokiteshvara, Trisong Detsen (742–803) as an emanation of Manjushri, and Ralpachan (815–883)

as one of Vajrapani. From here on

they are considered to be bearers of the Buddhist doctrine.

After their Buddhist origins had been assured, the

Tibetan kings posthumously took on all the characteristics of a world

ruler. As Dharmarajas (kings of

the law) they now represented the cosmic laws on earth. Likewise the “Great

Fifth” could now be celebrated as the most powerful secular king

reborn(Songtsen Gampo, who was likewise an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara) and through this

could combine the imperium

(worldly rule) with the sacerdotium

(spiritual power). This choice legitimated him as national hero and supreme

war lord and permitted a fundamental reform of the Lamaist state system

which S. J. Tambiah refers to as the “feudalization of the church”.

The great military commander and tribal chief,

Songtsen Gampo (617–650), who during his reign forged the highlands into a

state of unprecedented size, was thus included into the Buddhist pantheon.

Still today we can find impressive depictions of the feared warlord —

usually in full armor, and flanked by his two chief wives, the Chinese Wen

Cheng, and the Nepalese Bhrikuti.

The king is said to have commanded a force of

200,000 men. His conduct of war was considered extremely barbaric and the

“red faces”, as the Tibetans were known by the surrounding peoples, spread

fear and horror across all of central Asia. The extent to which Songtsen

Gampo was able to extend his imperium roughly corresponds to the territory over which the Fourteenth Dalai

Lama today still claims as his dominion. Hence, thanks to the “Great Fifth”

the geopolitical dimensions were also adopted from the sacred kingship.

From the point of view of a tantric interpretation

of history, however, the greatest deed of this ancient king (Songtsen

Gampo) was the nailing down of the earth mother, Srinmo, and the staking of her heart beneath the holiest of

holies in the land, the Jokhang temple.

The “Great Fifth”, as a confirmed ritualist, would surely have

considered the “mastering of the demoness” as the cause of Songtsen Gampo's

historical successes. Almost a thousand years later he too would precede

almost every political and military decision with a magic ritual.

One day, it is said, Songtsen Gampo appeared to

him in a dream and demanded of him that he manufacture a golden statue of

him (the king) in the “style of a Chakravartin”

and place this in the Jokhang temple. When, in the year 1651, the “Great

Fifth” visited locations at which the great king was once active, according

to the chronicles flowers began to rain from the skies there and the eight

Tibetan signs of luck floated through the air.

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama and the question of incarnation

On July 6, 1935, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama was

born as the child of ordinary people in a village by the name of Takster,

which means, roughly, “shining tiger”. In connection with our study of the

topic of gender it is interesting that the parents originally gave the boy

a girl’s name. He was called Lhamo

Dhondup, that is, “wish fulfilling goddess”. The androgyny of this

incarnation of Avalokiteshvara

was thus already signaled before his official recognition.

The story of his discovery has been told so often

and spectacularly filmed in the meantime that we only wish to sketch it

briefly here. After the death of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, the then regent

(Reting Rinpoche) saw mysterious letters in a lake which was dedicated to

the protective goddess Palden Lhamo,

which together with other visions indicated that the new incarnation of the

god-king was to be found in the northeast of the country in the province of

Amdo. A search commission was equipped in Lhasa and set out on the

strenuous journey. In a hut in the village of Takster a small boy is

supposed to have run up to one of the commissioners and demanded the

necklace of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama which he held in his hands. The monk

refused and would only give him it if the child could say who he was. “You

are a lama from Sera!”, the boy is said to have cried out in the dialect

which is only spoken in Lhasa. [6] Afterwards, from the objects laid out

before him he selected those which belonged to his predecessor; the others

he laid aside. The bodily examination performed on the child also revealed

the necessary five features which distinguish a Dalai Lama: The imprint of

a tiger skin on the thigh; extended eyelashes with curved lashes; large

ears; two fleshy protuberances on the shoulders which are supposed to

represent two rudimentary arms of Avalokiteshvara;

the imprint of a shell on his hand.

For understandable reasons the fact that a Chinese

dialect was spoken in the family home of His Holiness is gladly passed over

in silence. The German Tibet researcher, Matthias Hermanns, who was doing

field work in Amdo at the time of the discovery and knew the family of the

young Kundun well, reports that

the child could understand no Tibetan at all. When he met him and asked his

name, the boy answered in Chinese that he was called “Chi”. This was the

official Chinese name for the village of Takster (Hermanns, 1956, p. 319).

Under difficult circumstances the child arrived in Lhasa at the end of 1939

and was received there as Kundun,

the living Buddha. Already as an eight year old he received his first

introduction into the tantric teachings.

Every little tulku who is separated from his

family at a tender age misses the motherly touch. For the Fourteenth Dalai

Lama this role was taken over by his cook, Ponpo by name. Not at the death

of his mother, but rather at the demise of his substitute mother, Ponpo,