|

© Victor

& Victoria Trimondi

The Shadow of the Dalai Lama – Part II

– 10. The spearhead of the Shambhala war

10. THE SPEARHEAD OF THE

SHAMBHALA WAR

War in the Tibet of old on a number of occasions

meant the military intervention of various Mongolian tribes into the

internal affairs of the country. Over the course of time a deep cultural

connection with the warlike nomads from the north developed which

ultimately led to a complete Buddhization of

Mongolia. Today this is interpreted by Buddhist “historians” as a

pacification of the country and its inhabitants. But let us examine more

closely some prominent events in the history of Central

Asia under Buddhist control.

Genghis Khan as a Bodhisattva

The greatest conqueror of all humankind, at least

as far as the expansion of the territory under his control is concerned,

was Genghis Khan (1167–1227). He united the peoples of the Mongolian

steppes in Asia and from them formed a horseback army which struck fear

into the hearts of Europe and China just as much as it did in

the Islamic states. His way of conducting warfare was for the times

extremely modern. The preparations for an offensive usually took several

years. He had the strengths and weaknesses of his opponents studied in

detail. This was achieved by among other things a cleverly constructed

network of spies and agents. His notorious cavalry was neither chaotic nor

wild, nor as large as it was often said to be by the peoples that he

conquered. In contrast, they were distinguished by strict discipline, had

the absolutely best equipment, and were courageous, extremely effective,

and usually outnumbered by their enemies. The longer the preparations for

war were, the more rapidly the battles were decided, and that with a

merciless cruelty. Women and children found just as little pity as the aged

and the sick. If a city opposed the great Khan, every living creature

within it had to be exterminated, even the animals — the dogs and rats were

executed. Yet for those who submitted to him, he became a redeemer,

God-man, and prince of peace. To this day the Mongolians have not forgotten

that the man who conquered and ruled the world was of their blood.

Tactically at least, in wanting to expand into

Mongolia Tibetan Lamaism did well to declare Genghis Khan, revered as

divine, to be one of their own. It stood in the way of this move that the

world conqueror was no follower of the Buddhist teachings and trusted only

in himself, or in the shamanist religious practices of his ancestors. There

are even serious indications that he felt attracted to monotheistic ideas

in order to be able to legitimate his unique global dominion.

Yet through an appeal to their ADI BUDDHA system

the lamas could readily match their monotheistic competitors. According to

legend a contest between the religions did also took place before the

ruler’s throne, which from the Tibetan viewpoint was won by the Buddhists.

The same story is recounted by the Mohammedans, yet ends with the “ruler of

the world” having decided in favor of the Teachings of the Prophet. In

comparison, the proverbial cruelty of the Mongolian khan was no obstacle to

his fabricated “Buddhization”, since he could

without further ado be integrated into the tantric system as the fearful

aspect of a Buddha (a heruka) or as a bloodthirsty dharmapala (tutelary

god).Thus more and more stories were invented which portrayed him as a

representative of the Holy Doctrine (the dharma).

Among other things, Mongolian lamas constructed an

ancestry which traced back to a Buddhist Indian law-king and put this in

place of the zoomorphic legend common among the shamans that Genghis Khan

was the son of a wolf and a deer. Another story tells of how he was

descended from a royal Tibetan family. It is firmly believed that he was in

correspondence with a great abbot of the Sakyapa

sect and had asked him for spiritual protection. The following sentence

stands in a forged letter in which the Mongol addresses the Tibetan

hierarch: “Holy one! Well did I want to summon you; but because my worldly

business is still incomplete, I have not summoned you. I trust you from

here, protect me from there” (Schulemann, 1958,

p. 89). A further document “from his hand” is supposed to have freed the

order from paying taxes. In the struggle against the Chinese, Genghis Khan

— it is reported — prayed to ADI BUDDHA.

The Buddhization of Mongolia

But it was only after the death of the Great Khan

that the missionary lamas succeeded in converting the Mongolian tribes to Buddhism,

even if this was a process which stretched out over four centuries.

(Incidentally, this was definitely not true for all, then

a number took up the Islamic faith.) Various smaller contacts aside, the

voyage of the Sakya, Pandita

Kunga Gyaltsen, to the

court of the nomad ruler Godän Khan (in 1244),

stands at the outset of the conversion project, which

ultimately brought all of northern Mongolia under Buddhist

influence. The great abbot, already very advanced in years,

convinced the Mongolians of the power of his religion by healing Ugedai’s son of a serious illness. The records

celebrate their subsequent conversion as a triumph of civilization over

barbarism.

Some 40 years later (1279),

there followed a meeting between Chögyel Phagpa, likewise a Tibetan great abbot of the Sakyapa lineage, and Kublai Khan, the Mongolian

conqueror of China

and the founder of the Yuan dynasty. At these talks topics which concerned

the political situation of Tibet

were also discussed. The adroit hierarch from the Land

of Snows succeeded in persuading

the Emperor to grant him the title of “King of the Great and Valuable Law”

and thus a measure of worldly authority over the not yet united Tibet. In

return, the Phagpa lama initiated the Emperor

into the Hevajra Tantra.

Three hundred years later (in 1578), the Gelugpa abbot, Gyalwa Sonam Gyatso, met with Althan Khan and received from him the fateful name of

“Dalai Lama”. At the time he was only the spiritual ruler and in turn gave

the Mongolian prince the title of the “Thousand-Golden-Wheel turning World

Ruler”. From 1637 on the cooperation between the “Great Fifth” and Gushri Khan began. By the beginning of the 18th century

at the latest, the Buddhization of Mongolia was

complete and the country lay firmly in the hand of the Yellow Church.

But it would be wrong to believe that the

conversion of the Mongolian rulers had led to a fundamental rejection of

the warlike politics of the tribes. It is true that it was at times a

moderating influence. For instance, the Third Dalai Lama had demanded that

women and slaves no longer be slaughtered as sacrificial offerings during

the ancient memorial services for the deceased princes of the steppe. But

it would fill pages if we were to report on the cruelty and mercilessness

of the “Buddhist” Khans. As long as it concerned the combating of “enemies

of the faith”, the lamas were prepared to make any compromise regarding

violence. Here the aggressive potential of the protective deities (the dharmapala)

could be lived out in reality without limits. Yet to be fair one has to say

that both elements, the pacification and the militarization, developed in

parallel, as is indeed readily possible in the paradoxical world of the

tantric doctrines. It was not until the beginning of the 20th century that

the proverbial fighting spirit of the Mongolians would once more really

shine forth and then, as we shall see, combine with the martial ideology of

the Kalachakra Tantra.

Before the Communists seized power in Mongolia in

the twenties, more than a quarter of the male population

were simple monks. The main contingent of lamas belonged to the Gelugpa order and thus at least officially obeyed the

god-king from Lhasa.

Real power, however, was exercised by the supreme Khutuktu, the Mongolian term

for an incarnated Buddha being (in the Tibetan language: Kundun). At

the beginning of his term in office his authority only extended to

religious matters, then constitutionally the steppe land

of Genghis Khan had become a province of China.

In the year 1911 there was a revolt and the

“living Buddha”, Jebtsundamba Khutuktu,

was proclaimed as the first head of state (Bogd Khan) of the autonomous Mongolian peoples.

At the same time the country declared its independence. In the

constitutional decree it said: “We have elevated the Bogd,

radiant as the sun, myriad aged, as the Great Khan of Mongolia and his

consort Tsagaan Dar as the mother of the nation”

(Onon, 1989, p. 16). The great lama’s response

included the following: “After accepting the elevation by all to become the

Great Khan of the Mongolian Nation, I shall endlessly strive to spread the

Buddhist religion as brightly as the lights of the million suns ...” (Onon, 1989, p. 18).

From now on, just as in Tibet

a Buddhocracy with the incarnation of a god at

its helm reigned in Mongolia.

In 1912 an envoy of the Dalai Lama signed an agreement with the new head of

state in which the two hierarchs each recognized the sovereignty of the

other and their countries as autonomous states. The agreement was to be

binding for all time and pronounced Tibetan Buddhism to be the sole state

religion.

Jabtsundamba Khutuktu

(1870–1924) was not a native Mongol, but was born in Lhasa as the son of a senior civil

servant in the administration of the Dalai Lama. At the age of four his

monastic life began in Khüre, the Mongolian

capital at the time. Even as a younger man he led a dissolute life. He

loved women and wine and justified his liberties with tantric arguments.

This even made its way into the Mongolian school books of the time, where

we are able to read that there are two kinds of Buddhism: the “virtuous

way” and the “mantra path”. Whoever follows the latter, “strolls, even

without giving up the drinking of intoxicating beverages, marriage, or a

worldly occupation, if he contemplates the essence of the Absolute, ... along the path of the great yoga master.”

(Glasenapp, 1940, p. 24). When on his visit to Mongolia

the Thirteenth Dalai Lama made malicious comments about dissoluteness of

his brother-in-office, the Khutuktu is said to

have foamed with rage and relations between the two sank to a new low.

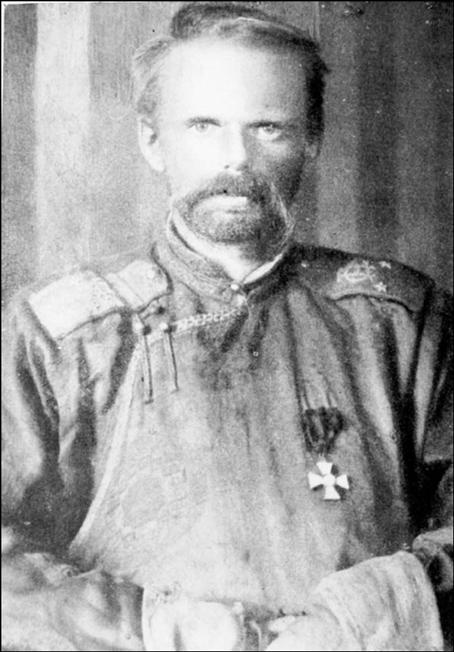

Jebtsundamba

Khutuktu, the

eighth Bogdo-gegen

The “living Buddha” from Mongolia

was brutal to his subjects and not rarely

overstepped the border to cruelty. He is accredited with numerous

poisonings. It was not entirely without justification that he trusted

nobody and suspected all. Nonetheless he possessed political acumen, an

unbreakable ambition, and also a noteworthy audacity. Time and again he understood

how, even in the most unfathomable situations, to seize political power for

himself, and survived as head of state even after the Communists had

conquered the country. His steadfastness in the face of the Chinese

garnered him the respect of both ordinary people and the nobility.

There had barely been a peaceful period for him.

Soon after its declaration of independence (in 1911) the country became a

plaything of the most varied interests: the Chinese, Tsarist Russians,

Communists, and numerous national and regional groupings attempted to gain

control of the state. Blind and marked by the consumption of alcohol, the Khutuktu died in 1924. The Byelorussian, Ferdinand Ossendowski, who was fleeing through the country at the

time attributes the following prophecy and vision to the Khutuktu, which, even if it is not historically

authenticated, conjures up the spirit of an aggressive pan-Mongolism: “Near

Karakorum and on the shores of Ubsa Nor I see the

huge multi-colored camps. ... Above them I see the old banners of Jenghiz Khan, of the kings of Tibet, Siam, Afghanistan,

and of Indian princes; the sacred signs of all the Lamaite

Pontiffs; the coats of arms of the Khans of the Olets;

and the simple signs of the north-Mongolian tribes. .... There is the roar

and crackling of fire and the ferocious sound of battle. Who is leading

these warriors who there beneath the reddened sky

are shedding their own and others’ blood? ... I see ... a new great

migration of peoples, the last march of the Mongols …" (Ossendowski, 1924, pp. 315-316).

In the same year that Jabtsundamba

Khutuktu died the “Mongolian Revolutionary

People’s Party” (the Communists) seized complete governmental control,

which they were to exercise for over 60 years. Nonetheless speculation

about the new incarnation of the “living Buddha” continued. Here the

Communists appealed to an old prediction according to which the eighth Khutuktu would be reborn as a Shambhala general and would

thus no longer be able to appear here on earth. But the cunning lamas

countered with the argument that this would not hamper the immediate

embodiment of the ninth Khutuktu. It was decided

to approach the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and the Ninth Panchen

Lama for advice. However, the Communist Party prevailed and in 1930

conducted a large-scale show trial of several Mongolian nobles and

spiritual leaders in connection with this search for a new incarnation.

There were attempts in Mongolia at the time to make

Communist and Buddhist ideas compatible with one another. In so doing, lamas

became excited about the myth that Lenin was a reincarnation of the

historical Buddha. But other voices were likewise to be heard. In a

pamphlet from the twenties we can also read that “Red Russia and Lenin are

reincarnation of Langdarma, the enemy of the

faith” (Bawden, 1969, p. 265). Under Josef Stalin

this variety of opinion vanished for good. The Communist Party proceeded

mercilessly against the religious institutions of Mongolia,

drove the monks out of the monasteries, had the temples closed and forbade

any form of clerical teaching program.

The Mongolian Shambhala myth

We do not intend to consider in detail the recent

history of Mongolia.

What primarily interests us are the tantric

patterns which had an effect behind the political stage. Since the 19th

century prophetic religious literature has flourished in the country. Among

the many mystic hopes for salvation, the Shambhala myth ranks as the foremost. It has always accompanied the

Mongolian nationalist movement and is today enjoying a powerful renaissance

after the end of Communism. Up until the thirties it was almost

self-evident for the Lamaist milieu of the

country that the conflicts with China

and Russia

were to be seen as a preliminary skirmish to a future, worldwide, final

battle which would end in a universal victory for Buddhism. In this, the

figures of the Rudra Chakrin,

of the Buddha Maitreya,

and of Genghis Khan were combined

into an overpowering messianic figure who would

firstly spread unimaginable horror so as to then lead the converted masses,

above all the Mongols as the chosen people, into paradise. The soldiers of

the Mongolian army proudly called themselves “Shambhala warriors”. In a

song of war from the year 1919 we may read

We raised the yellow flag

For the greatness of the Buddha

doctrine;

We, the pupils of the Khutuktu,

Went into the battle of Shambhala!

(Bleichsteiner, 1937, p.

104).

Five years later, in 1924, the Russian, Nicholas

Roerich, met a troop of Mongolian horsemen in Urga

who sang:

Let us die in this war,

To be reborn

As horsemen of the Ruler

of Shambhala

(Schule der Lebensweisheit,

1990, p. 66).

He was informed in mysterious tones that a year

before his arrival a Mongol boy had been born, upon whom the entire

people’s hopes for salvation hung, because he was an incarnation of Shambhala.

The Buriat, Agvan Dorjiev, a confidante

of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, about him we still have much to report,

persistently involved himself in every event which has affected Mongolia

since the beginning of the twentieth century. “It was his special

contribution”, John Snelling writes, “to expand

pan-Mongolism, which has been called 'the most powerful single idea in

Central Asia in the twentieth century', into the more expansive

pan-Buddhism, which, as we have already noted, he based upon the Kalachakra

myths, including the legend of the messianic kingdom of Shambhala” Snelling, 1993, p. 96).

The Shambhala myth

lived on in the underground after Communist accession to power, as if a

military intervention from out of the mythic kingdom were imminent. In 1935

and 1936 ritual were performed in Khorinsk in

order to speed up the intervention by the king of Shambhala. The lamas produced

postcards on which could be seen how the armies of Shambhala poured forth out of

a rising sun. Not without reason, the Soviet secret service suspected this

to be a reference to Japan,

whose flag carries the national symbol of the rising sun. In fact, the

Japanese did make use of the Shambhala legend in their own

imperialist interests and attempted to win over Mongolian lamas as agents

through appeals to the myth.

Dambijantsan, the bloodthirsty avenging lama

To what inhumanity and cruelty the tantric scheme

can lead in times of war is shown by the story of the “avenging lama”, a

Red Hat monk by the name of Dambijantsan. He was

a Kalmyk from the Volga region who was imprisoned in Russia for

revolutionary activities. “After an adventurous flight”, writes Robert Bleichsteiner, “he went to Tibet

and India,

where he was trained in tantric magic. In the nineties he began his

political activities in Mongolia.

An errant knight of Lamaism, demon of the steppes, and tantric in the style

of Padmasambhava, he awakened vague hopes among

some, fear among others, shrank from no crime, emerged unscathed from all

dangers, so that he was considered invulnerable and unassailable, in brief,

he held the whole Gobi in his thrall” (Bleichsteiner,

1937,p. 110).

Dambijantsan believed himself to be the incarnation

of the west Mongolian war hero, Amursana. He succeeded over a number of years in

commanding a relatively large armed force and in executing a noteworthy

number of victorious military actions. For these he was awarded

high-ranking religious and noble titles by the “living Buddha” from Urga. The Russian, Ferdinand Ossendowski,

reported of him, albeit under another name (Tushegoun

Lama) [1], that “Everyone who disobeyed his orders perished. Such a one

never knew the day or the hour when, in his yurta or beside his galloping

horse on the plains, the strange and powerful friend of the Dalai Lama

would appear. The stroke of a knife, a bullet or strong fingers strangling

the neck like a vise accomplished the justice of the plans of this miracle

worker” (Ossendowski, 1924, p. 116). There was in

fact the rumor that the god-king from Lhasa

had honored the militant Kalmyk.

Dambijantsan’s form of warfare was of a calculated

cruelty which he nonetheless regarded as a religious act of virtue. On

August 6, 1912, after the taking of Khobdo, he

had Chinese and Sarten prisoners slaughtered

within a tantric rite. Like an Aztec sacrificial priest, in full regalia,

he stabbed them in the chest with a knife and tore their hearts out with

his left hand. He laid these together with parts of the brain and some

entrails in skull bowls so as to offer them up as bali sacrifices to the

Tibetan terror gods. Although officially a governor of the Khutuktu, for the next two years he conducted himself

like an autocrat in western Mongolia and tyrannized a huge territory with a

reign of violence “beyond all reason and measure” (Bawden,

1969, p. 198). On the walls of the yurt he live in hung the peeled skins of

his enemies.

It was first the Bolsheviks who clearly bothered

him. He fled into the Gobi desert and

entrenched himself there with a number of loyal followers in a fort. His

end was just as bloody as the rest of his life. The Russians sent out a

Mongolian prince who pretended to be an envoy of the “living Buddha”, and

thus gained entry to the camp without harm. In front of the unsuspecting

“avenging lama” he fired off six shots at him from a revolver. He then tore

the heart from the body of his victim and devoured it before the eyes of

all present, in order — as he later said — to frighten and horrify his

followers. He thus managed to flee. Later he returned to the site with the

Russians and collected the head of Dambijantsan

as proof. But the “tearing out and eating of the heart” was in this case

not just a terrible means of spreading dread, but also part of a

traditional cult among the Mongolian warrior caste, which was already

practiced under Genghis Khan and had survived over the centuries. There is

also talk of it in a passage from the Gesar epic which we have

already quoted. It is likewise found as a motif in Tibetan thangkas: Begtse, the highly revered war god, swings a sword in

his right hand whilst holding a human heart to his mouth with his left.

In light of the dreadful tortures of which the

Chinese army was accused, and the merciless butchery with which the

Mongolian forces responded, an extremely cruel form of warfare was the rule

in Central Asia in the nineteen twenties.

Hence an appreciation of the avenging lama has arisen among the populace of

Mongolia

which sometimes extends to a glorification of his life and deeds. The

Russian, Ossendowski, also saw in him an almost

supernatural redeemer.

Von Ungern Sternberg: The “Order of

Buddhist Warriors”

In 1919 the army of the Byelorussian general,

Roman von Ungern Sternberg, joined up with Dambijantsan. The native Balt

was of a similar cruelly eccentric nature to the “avenger lama”. Under

Admiral Kolchak he first established a Byelorussian bastion in the east

against the Bolsheviks. He saw the Communists as “evil spirits in human

shape” (Webb, 1976, p. 202). Later he went to Mongolia.

Through his daredevilry he there succeeded in

building up an army of his own and positioning himself at its head. This

was soon to excite fear and horror because of its atavistic cruelty. It

consisted of Russians, Mongolians, Tibetans, and Chinese. According to Ossendowski, the Tibetan and Mongolian regiments wore a

uniform of red jackets with epaulettes upon which the swastika of Genghis

Khan and the initials of the “living Buddha” from Urga

were emblazoned. (In the occult scene von Ungern

Sternberg is thus seen as a precursor of German national socialism.)

In assembling his army the baron applied the

tantric “law of inversion” with utmost precision. The hired soldiers were

firstly stuffed with alcohol, opium, and hashish to the point of collapse and

then left to sober up overnight. Anyone who now still drank was shot. The

General himself was considered invulnerable. In one battle 74 bullets were

caught in his coat and saddle without him being harmed. Everyone called the

Balt with the shaggy moustache and tousled hair

the “mad baron”. We have at hand a bizarre portrait from an eyewitness who

saw him in the last days before his defeat: “The baron with his head

dropped to his chest, silently rode in front of his troops. He had lost his

hat and clothing. On his naked chest numerous Mongolian talismans were

hanging on a bright yellow cord. He looked like the incarnation of a

prehistoric ape man. People were afraid even to look at him” (quoted by

Webb, 1976, p. 203).

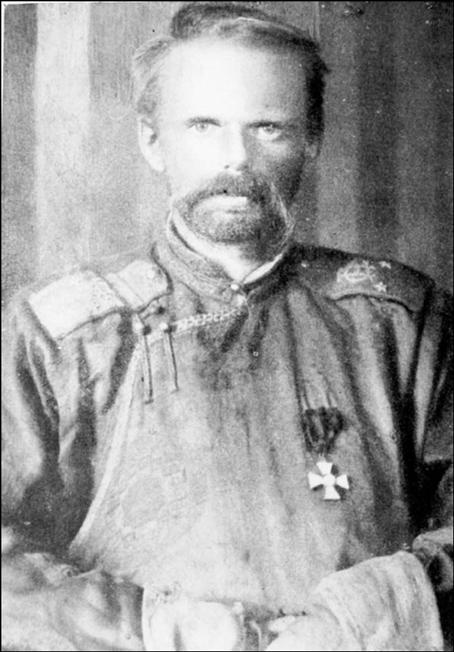

Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg.

This man succeeded in bringing the Khutuktu, driven away by the Chinese, back to Urga. Together with him he staged a tantric defense

ritual against the Red Army in 1921, albeit without much success. After

this, the hierarch lost trust in his former savior and is said to have made

contact with the Reds himself in order to be rid of the Balt.

At any rate, he ordered the Mongolian troops under the general’s command to

desert. Von Ungern Sternberg was then captured by

the Bolsheviks and shot. After this, the Communists pushed on to Urga and a year later occupied the capital. The Khutuktu had acted correctly in his own interests, then

until his death he remained at least pro

forma the head of state, although real power was transferred step by

step into the hands of the Communist Party.

All manner of occult speculations surround von Ungern Sternberg, which may essentially be traced to

one source, the best-seller we have already quoted several times by the

Russian, Ferdinand Ossendowski, with the German

title of Tiere, Menschen, Götter

[English: Beasts, Men and Gods]. The book as a whole is seen by

historians as problematic, but is, however, considered authentic in regard

to its portrayal of the baron (Webb, 1976, p. 201). Von Ungern

Sternberg quite wanted to establish an “order of military Buddhists”. “For

what?”, Ossendowski has

him ask rhetorically. “For the protection of the processes of evolution of

humanity and for the struggle against revolution, because I am certain that

evolution leads to the Divinity and revolution to bestiality” (Ossendowski, 1924, p. 245). This order was supposed to

be the elite of an Asian state, which united the Chinese, the Mongolians,

the Tibetans, the Afghans, the Tatars, the Buriats,

the Kyrgyzstanis, and the Kalmyks.

After calculating his horoscope the lamas

recognized in von Sternberg the incarnation of the mighty Tamerlan (1336-1405), the founder of the second

Mongolian Empire. The general accepted this recognition with pride and joy, and as an embodiment of the great Khan drafted his

vision of a world empire as a “military and moral defense against the

rotten West…" (Webb, 1976, p. 202). “In Asia there will be a great

state from the Pacific and Indian Oceans to the shore of the Volga”,

Ossendowski presents the baron as prophesying.

“The wise religion of Buddha shall run to the north and the west. It will

be the victory of the spirit. A conqueror and leader will appear stronger

and more stalwart than Jenghiz Khan

.... and he will keep power in his hands

until the happy day when, from his subterranean capital, shall emerge the

king of the world” (Ossendowski, 1924, p. 265).

Here he had uttered the key phrase which continues

to this day to hold the occult scene of the West enthralled, the “king of

the world”. This figure is supposed to govern in a kingdom below the ground

somewhere in Central Asia and from here

exercise an influence on human history. Even if Ossendowski

refers to his magic empire under the name of Agarthi, it is only a variant

upon or supplement to the Shambhala myth.[2] His “King of the World” is identical to the ruler

of the Kalachakra

kingdom. He “knows all the forces of the world and reads all the souls of

humankind and the great book of their destiny. Invisibly he rules eight

hundred million men on the surface of the earth and they will accomplish

his every order” (Ossendowski, 1924, p. 302).

Referring to Ossendowski, the French occultist,

René Guénon, speculates that the Chakravartin

may be present as a trinity in our world of appearances: in the figure of

the Dalai Lama he represents spirituality, in the person of the Panchen Lama knowledge, and in his emanation as Bogdo Khan (Khutuktu) the art

of war (Guénon, 1958, p. 37).

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Mongolia

Since the end of the fifties the pressure on the remainder

of the “Yellow Church” in Mongolia has slowly declined.

In the year 1979 the Fourteenth Dalai Lama visited for the first time. Moscow, which was involved in a confrontation with China, was

glad of such visits. However it was not until 1990 that the Communist Party

of Mongolia relinquished its monopoly on power. In 1992 a new democratic

constitution came into effect.

Today (in 1999) the old monasteries destroyed by

the Communists are being rebuilt, in part with western support. Since the

beginning of the nineties a real “re-Lamaization”

is underway among the Mongolians and with it a renaissance of the Shambhala myth and a renewed spread of the Kalachakra

ritual. The Gelugpa order is attracting so many

new members there that the majority of the novices cannot be guaranteed a

proper training because there are not enough tantric teachers. The

consequence is a sizeable army of unqualified monks, who not

rarely earn their living through all manner of dubious magic

practices and who represent a dangerous potential for a possible wave of

Buddhist fundamentalism.

The person who with great organizational skill is

supervising and accelerating the “rebirth” of Lamaism in Mongolia

goes by the name of Bakula Rinpoche,

a former teacher of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and his right hand in the

question of Mongolian politics. The lama, recognized as a higher tulku, surprisingly also functions as an Indian

ambassador in Ulan Bator alongside his

religious activities, and is accepted and supported in this dual role as

ambassador for India

and as a central figure in the “re-Lamaization

process” by the local government. In September of 1993 he had an urn

containing the ashes of the historical Buddha brought to Mongolia for several weeks from India, a

privilege which to date no other country has been accorded by the Indian

government. Bakula enjoys such a great influence

that in 1994 he announced to the Mongolians that the ninth incarnation of

the Jabtsundamba Khutuktu,

the supreme spiritual figure of their country, had been discovered in India.

The Dalai Lama is aware of the great importance of

Mongolia

for his global politics. He is constantly a guest there and conducts

noteworthy mass events (in 1979, 1982, 1991, 1994, and 1995). In Ulan Bator in 1996

the god-king celebrated the Kalachakra ritual in front of a huge, enthusiastic

crowd. When he visited the Mongolian Buriats in Russia in

1994, he was asked by them to recognize the greatest military leader of the

world, Genghis Khan, as a “Bodhisattva”. The winner of the Nobel peace

prize smiled enigmatically and silently proceeded to another point on the

agenda. The Kundun enjoys a boundless reverence

in Mongolia as in no

other part of the world (except Tibet). The grand hopes of this

impoverished people who once ruled the world hang on him. He appears to many Mongolians to be the savior who can lead them

out of the wretched financial state they are currently in and restore their

fame from the times of Genghis Khan.

Footnotes:

[2] Marco Pallis

is of the opinion that Ossendowski has simply

substituted the name Agarthi for Shambhala, because the former

was very well known in Russia

as a “world center”, whilst the name Shambhala had no associations

(Robin, 1986, pp. 314-315).

Next Chapter:

11. THE

SHAMBHALA MYTH AND THE WEST

|