|

© Victor

& Victoria Trimondi

The

Shadow of the Dalai Lama – Part II – 14. China’s metaphysical rivalry with

Tibet

14. CHINA’S

METAPHYSICAL

RIVALRY WITH TIBET

The Central Asian power which for centuries engaged

the Tibetan Buddhocracy in the deepest rivalry

was the Chinese Empire. Even if the focus of current discussions about

historical relations between the two countries is centered on questions of

territory, we must upon closer inspection regard this as the projected

object of the actual dispute. Indeed, hidden behind the state-political

facade lies a much more significant, metaphysically motivated power

struggle. The magic/exotic world of Lamaism and the outflow of the major

and vital rivers from the mountainous countries to the west led to the

growth of an idea in the “Middle Kingdom” that events in Tibet had a

decisive influence on the fate of their own country. The fates of the “Land of Snows” and China were

seen by both sides as being closely interlinked. At the beginning of the

twentieth century, leading Tibetans told the Englishman, Charles Bell, that

Tibet

was the “root of China”

(Bell, 1994, p.114). As absurd as it may sound, the Chinese power elite

never completely shook off this belief and they thus treated their Tibetan

politics especially seriously.

In addition the rulers of the two nations, the

“Son of Heaven” (the Chinese Emperor) and the “Ocean Priest” (the Dalai

Lama), were claimants to the world throne and made the pretentious claim to

represent the center of the cosmos, from where they wanted to govern the

universe. As we have demonstrated in the vision guiding and fate of the

Empress Wu Zetian, the Buddhist idea of a Chakravartin

influenced the Chinese Empire from a very early stage (700 C.E.). During

the Tang dynasty the rulers of China were worshipped as

incarnations of the Bodhisattva Manjushri and as “wheel-turning kings” (Chakravartin).

Besides, it was completely irrelevant whether the

current Chinese Emperor was of a more Taoist, Confucian, or Buddhist

inclination, as the idea of a cosmocrat was

common to all three systems. Even the Tibetans apportioned him this role at

times, such as the Thirteenth Dalai Lama for example, who referred to the

Manchu rulers as Chakravartins

(Klieger, 1991, p. 32).

We should also not forget that several of the

Chinese potentates allowed themselves to be initiated into the tantras and naturally laid claim to the visions of

power articulated there. In 1279 Chögyel Phagpa, the grand abbot of the Sakyapa,

initiated the Mongolian conqueror of China and founder of the Yuan

dynasty, Kublai Khan, into the Hevajra Tantra. In 1746 the Qian

Long ruler received a Lamaist tantric initiation

as Chakravartin.

Further it was an established tradition to recognize the Emperor of China

as an emanation of the Bodhisattva Manjushri. This demonstrates that two Bodhisattvas could

also fall into earnest political discord.

Tibetan culture owes just as much to Chinese as it does to that of India. A

likeness of the great military leader and king, Songtsen

Gampo (617–650), who forged the highlands into a

single state of a previously unseen size is worshipped throughout all of Tibet . It shows him in full armor and flanked by his two

chief wives. According to legend, the Chinese woman, Wen

Cheng, and the Nepalese, Bhrikuti, were

embodiments of the white and the green Tara.

Both are supposed to have brought Buddhism to the “Land of Snows”.

[1]

History confirms that the imperial princess, Wen Cheng, was accompanied by cultural goods from China that

revolutionized the whole of Tibetan community life. The cultivation of

cereals and fruits, irrigation, metallurgy, calendrics,

a school system, weights and measures, manners and clothing — with great

open-mindedness the king allowed these and similar blandishments of

civilization to be imported from the “Middle Kingdom”. Young men from the

Tibetan nobility were sent to study in China and India. Songtsen Gampo also made

cultural loans from the other neighboring states of the highlands.

These Chinese acts of peace and cultural

creativity were, however, preceded on the Tibetan side by a most aggressive

and imperialist policy of conquest. The king was said to have commanded an

army of 200,000 men. The art of war practiced by this incarnation of the

“compassionate” Bodhisattva, Avalokiteshvara, was

considered extremely barbaric and the “red faces”, as the Tibetans were

called, spread fear and horror through all of Central

Asia. The size to which Songtsen Gampo was able to expand his empire corresponds roughly

to that of the territory currently claimed by the Tibetans in exile as

their area of control.

Since that time the intensive exchange between the

two countries has never dried up. Nearly all the regents of the Manchu

dynasty (1644–1912) right up to the Empress Dowager Ci

Xi felt bound to Lamaism on the basis of their Mongolian origins, although

they publicly espoused ideas that were mostly Confucian. Their belief led

them to have magnificent Lamaist temples built in

Beijing.

There have been a total of 28 significant Lama shrines built in the

imperial city since the 18th century. Beyond the Great Wall, in the

Manchurian — Mongolian border region, the imperial families erected their

summer palace. They had an imposing Buddhist monastery built in the

immediate vicinity and called it the “Potala”

just like the seat of the Dalai Lama. In her biography, the imperial

princess, The Ling, reports that tantric rituals were still being held in

the Forbidden City at the start of the

twentieth century (quoted by Klieger, 1991, p.

55). [2]

If a Dalai Lama journeyed to China then

this was always conducted with great pomp. There was constant and

debilitating squabbling about etiquette, the symbolic yardstick for the

rank of the rulers meeting one another. Who first greeted whom, who was to

sit where, with what title was one addressed — such questions were far more

important than discussions about borders. They reflect the most subtle

shadings of the relative positions within a complete cosmological scheme. As

the “Great Fifth” entered Beijing

in 1652, he was indeed received like a regnant prince, since the ruling

Manchu Emperor, Shun Chi, was much drawn to the Buddhist doctrine. In farewelling the hierarch he showered him with valuable

gifts and honored him as the “self-creating Buddha and head of the valuable

doctrine and community, Vajradhara Dalai Lama” (Schulemann,

1958, p. 247), but in secret he played him off against the Panchen Lama.

The cosmological chess game went on for centuries

without clarity ever being achieved, and hence for both countries the

majority of state political questions remained unanswered. For example, Lhasa was obliged to

send gifts to Beijing

every year. This was naturally regarded by the Chinese as a kind of tribute

which demonstrated the dependence of the Land of Snows.

But since these gifts were reciprocated with counter-presents, the Tibetans

saw the relationship as one between equal partners. The Chinese countered

with the establishment of a kind of Chinese governorship in Tibet under

two officials known as Ambane. Form a Chinese point of view they represented

the worldly administration of the country. So that they could be played off

against one another and avoid corruption, the Ambane were always dispatched

to Tibet

in pairs.

The Chinese also tried to gain influence over the Lamaist politics of incarnation. Among the Tibetan and

Mongolian aristocracy it was increasingly the case that children from their

own ranks were recognized as high incarnations. The intention behind this

was to make important clerical posts de

facto hereditary for the Tibetan noble clans. In order to hamper such

familial expansions of power, the Chinese Emperor imposed an oracular

procedure. In the case of the Dalai Lama three boys were to always be sought

as potential successors and then the final decision would be made under

Chinese supervision by the drawing of lots. The names and birth dates of

the children were to be written on slips of paper, wrapped in dough and

laid in a golden urn which the Emperor Kien Lung

himself donated and had sent to Lhasa

in 1793.

Mao Zedong: The Red Sun

But did the power play between the two countries

over the world throne end with the establishment of Chinese Communism in Tibet? Is

the Tibetan-Chinese conflict of the last 50 years solely a confrontation

between spiritualism and materialism, or were there “forces and powers” at

work behind Chinese politics which wanted to establish Beijing as the center of the world at Lhasa’ expense?

“Questions of legitimation have plagued all

Chinese dynasties”, writes the Tibetologist

Elliot Sperling with regard to current Chinese

territorial claims over Tibet, „Questions of legitimation

have plagued all Chinese dynasties”, writes the Tibetologist

Elliot Sperling with regard to current Chinese

territorial claims over Tibet, „Traditionally such questions revolved

around the basic issue of whether a given dynasty or ruler possessed 'The

Mandate of Heaven’. Among the signs that accompanied possession of The

Mandate was the

ability to unify the country and overcome all rival claimants for the

territory and the throne of China.

It would be a mistake not to view the present regime within this tradition”

(Tibetan Review, August 1983, p.

18). But to put Sperling’s interesting thesis to the test, we need to

first of all consider a man who shaped the politics of the Communist Party

of China like no other and was worshipped by his followers like a god: Mao Zedong.

According to Tibetan reports, the occupation of Tibet by

the Chinese was presaged from the beginning of the fifties by numerous

“supernatural” signs: whilst meditating in the Ganden

monastery the Fourteenth Dalai Lama saw the statue of the terror deity Yamantaka

move its head and look to the east with a fierce expression. Various

natural disasters, including a powerful earthquake and droughts befell the

land. Humans and animals gave birth to monsters. A comet appeared in the

skies. Stones became loose in various temples and fell to the ground. On September 9, 1951 the

Chinese People’s Liberation Army marched into Lhasa.

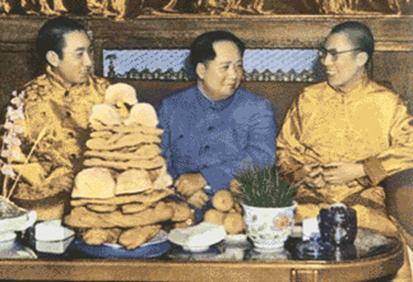

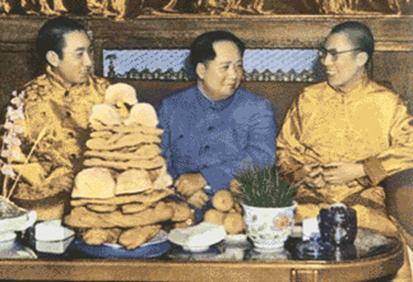

The Panchen Lama, Mao Zedong, the Dalai Lama

Before he had to flee, the young Dalai Lama had a

number of meetings with the “Great Chairman” and was very impressed by him.

As he shook Mao Zedong by the hand for the first time, the Kundun in his

own words felt he was

“in the presence of a strong magnetic force” (Craig, 1997, p.

178). Mao too felt the need to make a metaphysical assessment of the

god-king: “The Dalai Lama is a god, not a man”, he said and then qualified

this by adding, “In any case he is seen that way by the majority of the

Tibetan population” (Tibetan Review,

January 1995, p. 10). Mao chatted with the god-king about religion and

politics a number of times and is supposed to have expressed varying and

contradictory opinions during these conversations. On one occasion,

religion was for him “opium for the people” in the classic Marxist sense,

on another he saw in the historical Buddha a precursor of the idea of

communism and declared the goddess Tara

to be a “good woman”.

The twenty-year-old hierarch from Tibet

looked up to the fatherly revolutionary from China with admiration and even

nurtured the wish to become a member of the Communist Party. He fell, as

Mary Craig puts it, under the spell of the red Emperor (Craig, 1997, p.

178). “I have heard chairman Mao talk on different matters”, the Kundun

enthused in 1955, “and I received instructions from him. I have come to the

firm conclusion that the brilliant prospects for the Chinese people as a

whole are also the prospects for us Tibetan people; the path of our entire

country is our path and no other” (Grunfeld,

1996, p. 142)

Mao Zedong, who at that time was pursuing a

gradualist politics, saw in the young Kundun a powerful instrument

through which to familiarize the feudal and religious elites of the Land of Snows with his multi-ethnic

communist state. In a 17-point program he had conceded the “ national regional autonomy [of Tibet]

under the leadership of the Central People's Government”, and assured that

the “existing political system”, especially the “status, functions and

powers of the Dalai Lama”, would remain untouched (Goldstein, 1997, p. 47).

The Great Proletarian

Cultural Revolution

After the flight of the Dalai Lama, the 17-point

program was worthless and the gradualist politics of Beijing at an end. But it was first under

the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” (in the mid-sixties) that China’s

attitude towards Tibet

shifted fundamentally. Within a tantric conception of history the Chinese

Cultural Revolution has to be understood as a period of chaos and anarchy.

Mao Zedong himself had– like a skilled Vajra master — deliberately

evoked a general disorder so as to establish a paradise on earth after the

destruction of the old values: “A great chaos will lead to a new order”, he

wrote at the beginning of the youth revolt (Zhisui,

1994, p. 491). All over the country, students, school pupils, and young

workers took to the land to spread the ideas of Mao Zedong. The “Red Guard”

of Lhasa also understood itself to be the agent of its “Great Chairman”, as

it published the following statement in December 1966: “We a group of

lawless revolutionary rebels will wield the iron sweepers and swing the

mighty cudgels to sweep the old world into a mess and bash people into

complete confusion. We fear no gales and storms, nor flying sands and

moving rocks ... To rebel, to rebel, and to rebel through to the end in

order to create a brightly red new world of this proletariat” (Grunfeld, 1996, p. 183).

Although it was the smashing of the Lamaist religion which lay at the heart of the red

attacks in Tibet,

one must not forget that it was not just monks but also long-serving

Chinese Party

cadres in Lhasa

and the Tibetan provinces who fell victim to the brutal subversion. Even if

it was triggered by Mao Zedong, the Cultural Revolution was essentially a

youth revolt and gave expression to a deep intergenerational conflict.

National interests did not play a significant role in these events. Hence,

many young Tibetans likewise participated in the rebellious demonstrations

in Lhasa,

something which for reasons that are easy to understand is hushed up these

days by Dharamsala.

Whether Mao Zedong approved of the radicality with which the Red Guard set to work remains

doubtful. To this day — as we have already reported — the Kundun

believes that the Party Chairman was not fully informed about the

vandalistic attacks in Tibet

and that Jiang Qing, his spouse, was the evildoer. [3]

Mao’s attitude can probably be best described by saying that in as far as

the chaos served to consolidate his position he would have approved of it,

and in as far as it weakened his position he would not. For Mao it was

solely a matter of the accumulation of personal power, whereby it must be

kept in mind, however, that he saw himself as being totally within the

tradition of the Chinese Emperor as an energetic concentration of the

country and its inhabitants. What strengthened him also strengthened the

nation and the people. To this extent he thought in micro/macrocosmic

terms.

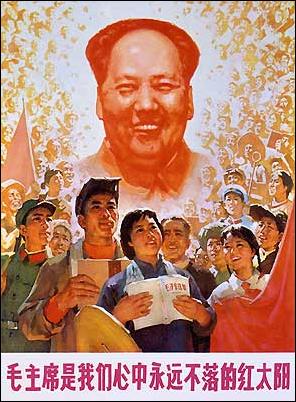

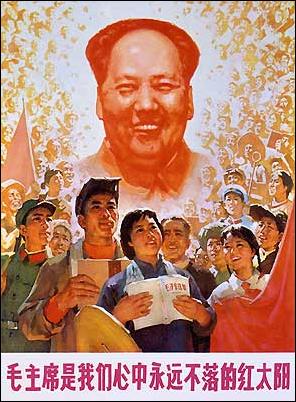

The “deification” of Mao

Zedong

The people’s tribune was also not free of the

temptations of his own “deification”: “The Mao cult”, writes his personal

physician, Zhisui, “spread in schools, factories,

and communes — the Party Chairman became a god” (Li Zhisui,

1994, p. 442). At heart, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution must be

regarded as a religious movement, and the “Marxist” from Beijing reveled in his worship as a

“higher being”.

Numerous reports of the “marvels of the thoughts

of Mao Zedong”, the countless prayer-like letters from readers in the

Chinese newspapers, and the little “red book” with the sacrosanct words of

the great helmsman, known worldwide as the “ bible of Mao “, and much more

make a religion of Maoism. Objects which factory workers gave to the “Great

Chairman” were put on display on altars and revered like holy relics. After

“men of the people” shook his hand, they didn’t wash theirs for weeks and

coursed through the country seizing the hands of passers

by under the impression that they could give them a little of Mao’s

energy. In some Tibetan temples pictures of the Dalai Lama were even

replaced with icons of the Chinese Communist leader.

In this, Mao was more like a red pontiff than a

people’s rebel. His followers revered him as a god-man in the face of whom

the individuality of every other mortal Chinese was extinguished. “The

'equality before god'", Wolfgang Bauer writes in reference to the

Great Chairman Mao Zedong, “really did illuminate, and allowed those who

felt themselves moved by it to become ‘brothers’, or monks [!] of some kind clothed in robes that were not just the

most lowly but thus also identical and that caused all individual

characteristics to vanish” (Bauer, 1989, p. 569).

The Tibetans, themselves the subjects of a

god-king, had no problems with such images; for them the “communist” Mao

Zedong was the “Chinese Emperor”, at least from the Cultural Revolution on.

Later, they even transferred the imperial metaphors to the “capitalist”

reformer Deng Xiaoping: “Neither the term 'emperor' nor 'paramount leader'

nor ‘patriarch’ appear in the Chinese constitution but nevertheless that is

the position Deng held ... he possessed political power for life, just like

the emperors of old” (Tibetan Review,

March 1997, p. 23).

Mao Zedong’s

“Tantrism”

The most astonishing factor, however, is that like

the Dalai Lama Mao Zedong also performed “tantric” practices, albeit à la chinoise.

As his personal physician, Li Zhisui reports,

even at great age the Great Chairman maintained an insatiable sexual

appetite. One concubine followed another. In this he imitated a privilege

that on this scale was accorded only to the Chinese Emperors. Like these,

he saw his affairs less as providing satisfaction of his lust and instead

understood them to be sexual magic exercises. The Chinese “Tantric” [4] is primarily a specialist in the extension of

the human lifespan. It is not uncommon for the old texts to recommend

bringing younger girls together with older men as energetic “fresheners”.

This method of rejuvenation is spread throughout all of Asia

and was also known to the high lamas in Tibet. The Kalachakra Tantra

recommends “the rejuvenation of a 70-year-old via a mudra [wisdom girl]" (Grünwedel, Kalacakra II,

p. 115).

Mao also knew the secret of semen retention: “He

became a follower of Taoist sexual practices,” his personal physician

writes, “through which he sought to extend his life and which were able to

serve him as a pretext for his pleasures. Thus he claimed, for instance,

that he needed yin shui (the water of yin, i.e., vaginal secretions) to complement his own yang (his masculine substance, the

source of his strength, power, and longevity) which was running low. Since

it was so important for his health and strength to build up his yang he dared not squander it. For

this reason he only rarely ejaculated during coitus and instead won

strength and power from the secretions of his female partners. The more yin shui

the Chairman absorbed, the more powerful his male substance became.

Frequent sexual intercourse was necessary for this, and he best preferred

to go to bed with several women at once. He also asked his female partners

to introduce him to other women — ostensibly so as to strengthen his life

force through shared orgies” (Li Zhisui, 1994,

pp. 387-388). He gave new female recruits a handbook to read entitled Secrets of an Ordinary Girl, so that

they could prepare themselves for a Taoist rendezvous with him. Like the

pupils of a lama, young members of the “red court” were fascinated by the

prospect of offering the Great Chairman their wives as concubines (Li Zhisui, 1994, pp. 388, 392).

The two chief symbols of his life can be regarded

as emblems of his tantric androgyny: the feminine “water” and masculine

“sun”. Wolfgang Bauer has drawn attention to the highly sacred significance

which water and swimming have in Mao’s symbolic world. His demonstrations

of swimming, in which he covered long stretches of the Yangtze, the “Yellow

River”, were supposed to “express the dawning of a new, bold undertaking,

through which a better world would arise: it was”, the author says, “a kind

of cultic action” which he “... completed with an almost ritual necessity

on the eve of the 'Cultural Revolution'" (Bauer, 1989, p. 566).

One of the most popular images of this period was

of Mao as the “Great Helmsman” who unerringly steered the masses through

the waves of the revolutionary ocean. With printruns

in the billions (!), poems such as the following were distributed among the

people:

Traveling upon the high seas we trust in the helmsman

As the ten thousand creatures in growing trust the sun.

If rain and dew moisten them, the sprouts become strong.

So we trust, when we push on with the revolution,

in the thoughts of Mao Zedong.

Fish cannot live away from water,

Melons do not grow outside their bed.

The revolutionary masses cannot stay apart

From the Communist Party.

The thoughts of Mao Zedong are their never-setting sun.

(quoted by Bauer,

1989, p. 567)

In this song we encounter the second symbol of

power in the Mao cult alongside water: the “red sun” or the “great eastern

sun”, a metaphor which — as we have already reported — later reemerges in

connection with the Tibetan “Shambhala warrior”, Chögyam Trungpa. „Long life to Chairman Mao, our supreme commander

and the most reddest red sun in our hearts”, sang

the cultural revolutionaries (Avedon, 1985, p. 349). The “thoughts of Mao Zedong” were also

“equated with a red sun that rose over a red age as it were, a veneration

that found expression in countless likenesses of Mao’s features surrounded

by red rays” (Bauer, 1989, p. 568). In this heliolatry, the Sinologist

Wolfgang Bauer sees a religious influence that originated not in China but

in the western Asian religions of light like Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism

that entered the Middle Kingdom during the Tang period and had become

connected with Buddhist ideas there (Bauer, 1989, p. 567). Indeed, the same

origin is ascribed to the Kalachakra Tantra by several scholars.

Mao Zedong as the never setting sun

Mao Zedong’s theory of

“blankness” also seems tantric. As early as 1958 he wrote that the China’s

weight within the family of peoples rested on the fact that “first of all

[it] is poor and secondly, blank. ... A blank sheet of paper has no stains,

and thus the newest and most beautiful words can be written on it, the

newest and most beautiful images painted on it” (quoted by Bauer, 1989, pp.

555-556). Bauer sees explicit traces of the Buddhist ideal of “emptiness”

in this: “The 'blank person', whose presence in Mao’s view is especially

pronounced among the Chinese people, is not just the 'pure', but also at

the same time also the 'new person’ in whom ... all the old organs in the

body have been exchanged for new ones, and all the old convictions for new

ones. Here the actual meaning of the spiritual transformation of the

Chinese person, deliberately imbuing all facets of the personality, bordering

on the mystic, encouraged with all the means of mass psychology, and which

the West with horror classifies as 'brainwashing', becomes apparent”

(Bauer, 1989, p. 556).

As if they wanted to exorcise their own repellant tantra practices through their projection onto their

main opponent, the Tibetans in exile appeal to Chinese sources to link the

Cultural Revolution with cannibalistic ritual practices. Individuals who

were killed during the ideological struggles became the objects of

cannibalism. At night and with great secrecy members of the Red Guard were

said to have torn out the hearts and livers of the murdered and consumed

them raw. There were supposed to have been occasions where people were

struck down so that their brains could be sucked out using a metal tube (Tibetan Review, March 1997, p. 22).

The anti-Chinese propaganda may arouse doubts about how much truth there is

in such accounts, yet should they really have taken place they too would

bring the revolutionary events close to a tantric pattern.

A spiritual rivalry

between the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and Mao Zedong?

The hidden religious basis of the Chinese Cultural

Revolution prevents us from describing the comprehensive opposition between

Mao Zedong and the Dalai Lama as an antinomy between materialism and

spirituality — an interpretation which the Tibetan lamas, the Chinese

Communists, and the West have all given it, albeit all with differing

evaluations. Rather, both systems (the Chinese and the Tibetan) stood — as

the ruler of the Potala and the regent of the Forbidden City had for centuries — in mythic contest

for the control of the world, both reached for the symbol of the “great

eastern sun”. Mao too had attempted to impose his political ideology upon

the whole of humanity. He applied the “theory of the taking of cities via

the land” and via the farmers which he wrote and put into practice in the

“Long March” as a revolutionary concept for the entire planet, in that he

declared the non-industrialized countries of Asia, Africa, and South

America to be “villages” that would revolt against the rich industrial

nations as the “cities”.

But there can only be one world ruler! In 1976,

the year in which the “red pontiff” (Mao Zedong) died, according to the

writings of the Tibetans in exile things threatened to take a turn for the

worse for the Tibetans. The state oracle had pronounced the gloomiest

predictions. Thereupon His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama withdrew into

retreat, the longest that he had ever made in India: “An extremely strict

practice”, he later commented personally, “which requires complete

seclusion over several weeks, linked to a very special teaching of the

Fifth Dalai Lama” (Levenson, 1992, p. 242). The

result of this “practice” was, as Claude B. Levenson

reports, the following: firstly there was “a major earthquake in China with

thousands of victims. Then Mao made his final bow upon the mortal stage.

This prompted an Indian who was close to the Tibetans to state, 'That’s

enough, stop your praying, otherwise the sky will fall on the heads of the

Chinese'" (Levenson, 1992, p. 242). In fact,

shortly before his death the “Great Chairman” was directly affected by this

earthquake. As his personal physician (who was present) reports, the bed

shook, the house swayed, and a nearby tin roof rattled fearsomely.

Whether or not this was a coincidence, if a secret

ritual of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama was conducted to “liberate” Mao Zedong,

it can only have been a matter of the voodoo-like killing practices from

the Golden Manuscript of the

“Great Fifth”. Further, it is clear from the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s

autobiography that on the day of Mao’s death he was busy with the Time Tantra. At that time [1976], the Kundun

says. „I was in Ladakh, part of the remote Indian

province of Jammu and Kashmir, where I was

conducting a Kalachakra

initiation. On the second the ceremony’s three days, Mao died. And the

third day, it rained all morning. But, in the afternoon, there appeared one

of the most beautiful rainbows I have ever seen. I was certain that it must be a good omen” (Dalai Lama

XIV, 1990, 222)

The post-Maoist era in Tibet

The Chinese of the Deng era recognized the error

of their politics during the Cultural Revolution and publicly criticized

themselves because of events in Tibet. An attempt was made to

correct the mistakes and various former restrictions were relaxed step by

step. As early as 1977 the Kundun was offered the chance to return to Tibet. This

was no subterfuge but rather an earnest attempt to appease. One could talk about

everything, Deng Xiaoping said, with the exception of total independence

for Tibet.

Thus, over the course of years, with occasional

interruptions, informal contacts sprang up between the representatives of

the Tibetans in exile and the Chinese Party cadres. But no agreement was

reached.

The Communist Party of China guaranteed the

freedom of religious practice, albeit with certain restrictions. For

example, it was forbidden to practice “religious propaganda” outside of the

monastery walls, or to recruit monks who were under 18 years old, so as to

protect children from “religious indoctrination”. But by and large the

Buddhist faith could be practiced unhampered, and it has bloomed like never

before in the last 35 years.

In the meantime hundreds of thousands of western

tourists have visited the “roof of the world”. Individuals and travel

groups of exiled Tibetans have also been permitted to visit the Land of Snows privately or were even

officially invited as “guests of state”. Among them has been Gyalo Thondup, the Dalai

Lama’s brother and military advisor, who conspired against the Chinese

Communists with the CIA for years and counted among the greatest enemies of

Beijing.

The Chinese were firmly convinced that the Kundun’s

official delegations would not arouse much interest among the populace. The

opposite was the case. Many thousands poured into Lhasa to see the brother of the Dalai

Lama.

But apparently this “liberal” climate could not and still cannot heal the deep wounds

inflicted after the invasion and during the Chinese occupation.

Up until 1998, the opposition to Beijing in Tibet was stronger than ever

before since the flight of the Dalai Lama, as the bloody rebellion of

October 1987 [5] and the since then

unbroken wave of demonstrations and protests indicates. For this reason a

state of emergency was in force in Lhasa

and the neighboring region until 1990. The Tibet researcher Ronald

Schwartz has published an interesting study in which he convincingly proves

that the Tibetan resistance activities conform to ritualized patterns.

Religion and politics, protest and ritual are blended here as well.

Alongside its communicative function, every demonstration thus possesses a

symbolic one, and is for the participants at heart a magic act which

through constant repetition is supposed to achieve the expulsion of the

Chinese and the development of a national awareness among the populace.

The central protest ceremony in the country

consists in the circling of the Jokhang Temple

by monks and laity who carry the Tibetan flag. This action is known as khorra and is

linked to a tradition of circumambulation. Since time immemorial the

believers have circled shrines in a clockwise direction with a prayer drum

in the hand and the om mani padme hum formula on their lips, on the one hand to

ensure a better rebirth, on the other to worship the deities dwelling

there. However, these days the khorra is linked — and this is historically recent —

with protest activity against the Chinese: Leaflets are distributed,

placards carried, the Dalai Lama is cheered. At the same time monks offer

up sacrificial cakes and invoke above all the terrible protective goddess, Palden Lhamo. As

if they wanted to neutralize the magic of the protest ritual, the Chinese

have begun wandering around the Jokhang in the

opposite direction, i.e., counterclockwise.

Those monks who were wounded and killed by the

Chinese security forces whilst performing the ritual in the eighties are

considered the supreme national martyrs. Their sacrificial deaths demanded

widespread imitation and in contrast to the Buddhist prohibition against

violence could be legitimated without difficulty. To sacrifice your life

does not contradict Buddhism, young monks from the Drepung

monastery told western tourists (Schwartz, 1994, p. 71).

Without completely justifying his claims, Schwartz

links the circling of the Jokhang with the vision

of the Buddhist world kingship. He refers to the fact that Tibet’s

first Buddhist ruler, Songtsen Gampo, built the national shrine and that his spirit is

supposed to be conjured up by the constant circumambulation: „Tibetans in

succeeding centuries assimilated Songtsen Gampo to the universal [!] Buddhist paradigm of the

ideal king, the Chakravartin

or wheel-turning king, who subdues demonic forces and establishes a polity

committed to promoting Dharma or

righteousness” (Schwartz, 1994, p. 33).

A link between the world ruler thus evoked and the

“tantric female sacrifice” is provided by the myth that the living heart of

Srinmo,

the mother of Tibet,

beats in a mysterious lake beneath the Jokhang

where it was once nailed fast with a dagger by the king, Songtsen Gampo. In the light

of the orientation of contemporary Buddhism, which remains firmly anchored

in the andocentric tradition, the ritual circling of the temple can hardly

be intended to free the earth goddess. In contrast, it can be assumed that

the monk’s concern is to strengthen the bonds holding down the female

deity, just as the earth spirits are nailed to the ground anew in every Kalachakra ritual.

After a pause of 25 years, the Tibetan New Year’s

celebration (Monlam), banned by the Chinese in

1960, are since1986 once more held in front of the Jokhang.

This religious occasion, which as we have shown above is symbolically

linked with the killing of King Langdarma, has

been seized upon by the monks as a chance to provoke the Chinese

authorities. But here too, the political protest cannot be separated from

the mythological intention. „Its final ceremony,” Schwartz writes of the

current Mönlam festivals, „which centres on Maitreya, the

Buddha of the next age, looks forward to the return of harmony to the world

with the re-emergence of the pure doctrine in the mythological future. The

demonic powers threatening society, and bringing strife and suffering, are

identified with the moral degeneration of the present age. The recommitment

of Tibet as a nation to the cause of Buddhism is thus a step toward the

collective salvation of the world” (Schwartz, 1994, p. 88) The ritual circling of the Jokhang and the feast held before the “cathedral” thus

do not just prepare for the liberation of Tibet from the Chinese yoke, but

also the establishment of a worldwide Buddhocracy

(the resurrection of the pure doctrine in a mythological future).

Considered neutrally, the current social situation

in Tibet

proves to be far more complex than the Tibetans in exile would wish.

Unquestionably, the Chinese have introduced many and decisive improvements

in comparison to the feudal state Buddhism of before 1959. But likewise there

is no question that the Tibetan population have

had to endure bans, suppression, seizures, and human rights violations in

the last 35 years. But the majority of these injustices and restrictions

also apply throughout the rest of China. The cultural and ethnic

changes under the influence of the Chinese Han and the Islamic Hui pouring in to the country may well be specific. Yet

here too, there are processes at work which can hardly be described (as the

“Dalai Lama” constantly does) as “cultural genocide”, but rather as a

result of the transformation from a feudal state via communism into a highly industrialized and multicultural

country.

A pan-Asian vision of the Kalachakra Tantra?

In this section we would like to discuss two

possible political developments which have not as far as we know been

considered before, because they appear absurd on the basis of the current

international state of affairs. However, in speculating about future events

in world history, one has to free oneself from the current position of the

fronts. The twentieth century has produced unimaginable changes in the

shortest of times, with the three most important political events being the

collapse of colonialism, the rise and fall of fascism, and that of

communism. How often have we had to experience that the bitterest of

enemies today become tomorrow’s best friends and vice versa. It is

therefore legitimate to consider the question of whether the current Dalai

Lama or one of his future incarnations can with an appeal to the Shambhala myth set himself up as the head of

a Central Asian major-power block with China as the leading nation. The

other question we want to consider is this — could the Chinese themselves

use the ideology of the Kalachakra Tantra to pursue an imperialist policy in the

future?

The Kalachakra Tantra and the

Shambhala myth had and still have a quite

exceptional popularity in Central Asia.

There, they hardly fulfill a need for world peace, but rather –especially

in Mongolia

–act as a symbol for dreams of becoming a major power. Thus the Shambhala

prophecy undoubtedly possesses the explosive force to power an aggressive Asia’s imperialist ideology. This idea is widespread

among the Kalmyks,

the various Mongolian tribes, the Bhutanese, the Sikkimese,

and the Ladhakis.

Even the Japanese made use of the Shambhala myth in the forties in order to

establish a foothold in Mongolia.

The power-hungry fascist elite of the island were generous in creating

political-religious combinations. They had known how to fuse Buddhism and Shintoism together into an imposing imperialist

ideology in their own country. Why should this not also happen with

Lamaism? Hence Japanese agents strove to create contacts with the lamas of Central Asia and Tibet (Kimura, 1990). They even

funded a search party for the incarnation of the Ninth Jebtsundampa

Khutuktu, the “yellow pontiff of the Mongolians”,

and sent it to Lhasa

for this purpose (Tibetan Review,

February 1991, p. 19). There were already close contacts to Japan under

the Thirteenth Dalai Lama; he was advised in military questions, for

example, was a Japanese by the name of Yasujiro Yajima (Tibetan Review, June 1982, pp. 8f.).

In line with the worldwide renaissance in all

religions and their fundamentalist strains it can therefore not be excluded

that Lamaism also regain a foothold in China and that after a return of the

Dalai Lama the Kalachakra

ideology become widespread there. It would then — as Edwin Bernbaum opines — just be seeds that had been sown before

which would sprout. „Through the Mongolians, the Manchus,

and the influence of the Panchen Lamas, the Kalachakra Tantra even had an

impact on China:

A major landmark of Peking, the Pai t’a, a

white Tibetan-style stupa on a hill overlooking

the Forbidden City, bears the emblem of

the Kalachakra Teaching, The Ten of Power.

Great Kalachakra Initiations were also given in Peking.” (Bernbaum,

1980, p. 286, f. 7) These were conducted in the thirties by the Panchen Lama.

Taiwan: A springboard for

Tibetan Buddhism and the Fourteenth Dalai Lama?

Yet as a decisive indicator of the potential

“conquest” of China

by Tibetan Buddhism, its explosive spread in Taiwan must be mentioned.

Tibetan lamas first began to missionize the

island in 1949. But their work was soon extinguished and could only be

resumed in 1980. From this point in time on, however, the tantric doctrine

has enjoyed a triumphal progress. The Deutsche Presse

Agentur (dpa) estimates

the number of the Kundun’s

followers in Taiwan to be between 200 and 300 thousand and increasing,

whilst the Tibetan Review of May

1997 even reports a figure of half a million. Over a hundred Tibetan

Buddhist shrines have been built. Every month around 100 Lamaist monks from all countries visit Taiwan “to

raise money for Tibetan temples around the world” there (Tibetan Review, May 1995, p. 11).

Increasingly, high lamas are also reincarnating

themselves in Taiwanese, i.e., Chinese, families. To date, four of these

have been “discovered” — an adult and three children — in the years 1987,

1990, 1991, and 1995. Lama Lobsang Jungney told a reporter that “Reincarnation can happen

wherever there is the need for Buddhism. Taiwan is a blessed land. It

could have 40 reincarnated lamas.” (Tibetan

Review, May 1995, pp. 10-11).

In March 1997 a spectacular reception was prepared

for the Dalai Lama in many locations around the country. The political

climate had shifted fundamentally. The earlier skepticism and reservation with which the god-king was treated by

officials in Taipei,

since as nationalists they did not approve of a detachment of the Land of Snows from China, had

given way to a warm-hearted atmosphere. His Holiness was praised in the

press as the “most significant visionary of peace” of our time. The

encounter with President Lee Teng-hui, at which

the two “heads of government” discussed spiritual topics among other

things, was celebrated in the media as a “meeting of the philosophy kings”

(Tibetan Review, May 1997, p.

15). The Kundun

has rarely been so applauded. “In fact,” the Tibetan Review writes, “the Taiwan visit was the most

politically charged of all his overseas visits in recent memory” (Tibetan Review, May 1997, p. 12). In

the southern harbor city of Kaohsiung

the Kundun

held a rousing speech in front of 50,000 followers in a sport stadium. The

Tibetan national flag was flown at every location where he stopped. The

Taiwanese government approved a large sum for the establishment of a Tibet

office in Taipei.

The office is referred to by the Tibetans in exile as a “de facto embassy”.

At around the same time, despite strong protest

from Beijing,

Tibetan monks brought an old tooth of the Buddha, which fleeing lamas had

taken with them during the Cultural Revolution, to Taiwan. The

mainland Chinese demanded the tooth back. In contrast a press report said,

“Taiwanese politicians expressed the hope [that] the relic would bring

peace to Taiwan,

after several corruption scandals and air disasters had cost over 200

people their lives” (Schweizerisch Tibetische Freundschaft, April 14, 1998 - Internet).

The spectacular development of Lamaist

Buddhism in Nationalist China (Taiwan) shows that the land

could be used as an ideal springboard to establish itself in a China freed

of the Communist Party. Ultimately, the Kundun says, the Chinese had collected negative karma through the

occupation of Tibet

and would have to bear the consequences of this (Tibetan Review, May 1997, p. 19). How could

this karma be better worked off than through the Middle Kingdom as a

whole joining the Lamaist faith.

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama

and the Chinese

The cultural relationships of the Kundun and of

members of his family to the Chinese are more complex and multi-layered

than they are perceived to be in the West. Let us recall that Chinese was spoken

in the home of the god-king’s parents in Takster.

In connection with the regent, Reting Rinpoche, the father of the Dalai Lama showed such a

great sympathy towards Beijing

that still today the Chinese celebrate him as one of their “patriots”

(Craig, 1997, p. 232). Two of His Holiness’s brothers, Gyalo

Thundup and Tendzin Choegyal, speak fluent Chinese. His impressive dealings

with Beijing

and his pragmatic politics have several times earned Gyalo

Thundup the accusation by Tibetans in exile that

he is a traitor who would sell Tibet to the Chinese (Craig,

1997, pp. 334ff.). Dharamsala has maintained

personal contacts with many influential figures in Hong

Kong and Taiwan

since the sixties.

Since the nineties, the constant exchange with the

Chinese has become increasingly central to the Kundun’s politics. In a

speech made in front of Chinese students in Boston (USA) on September 9, 1995, His

Holiness begins with a statement of how important the contact to China and

its people is for him. The usual constitutional statements and the

well-known demands for peace, human rights, religious freedom, pluralism,

etc. then follow, as if a western parliamentarian were campaigning for his

country’s democracy. Only at the end of his speech does the Kundun let

the cat out of the bag and nonchalantly proposes Tibetan Buddhism as

China’s new religion and thus, indirectly, himself as the Buddhist messiah:

“Finally it is my strong believe and hope that however small a nation Tibet

might be, we can still contribute to the peace and the prosperity of China.

Decades of communist rule and the commercial activities in recent years

both driven by extreme materialism, be it communist or capitalist, are

destroying much of China's

spiritual and moral values. A huge spiritual and moral vacuum is thus being

rapidly created in the Chinese society. In this situation, the Tibetan

Buddhist culture and philosophy would be able to serve millions of Chinese

brothers and sisters in their search for moral and spiritual values. After

all, traditionally Buddhism is not an alien philosophy to the Chinese

people” (Tibetan Review, October

1995, p. 18). Advertising for the Kalachakra initiation organized for the year 1999 in Bloomington, Indiana

was also available in Chinese. Since August 2000 one of the web sites run

by the Tibetans in exile has been appearing in Chinese.

In recent months (up until 1998), “pro-Chinese”

statements by the Kundun

have been issued more and more frequently. In 1997 he explained that the

materialistic Chinese could only profit from an adoption of spiritual

Lamaism. Everywhere, indicators of a re-Buddhization

of China

were already to be seen. For example, a high-ranking member of the Chinese

military had recently had himself blessed by the Mongolian great lama, Kusho Bakula Rinpoche, when the latter was in Beijing briefly. Another Chinese officer

had participated in a Lamaist event seated in the

lotus position, and a Tibetan woman had told him how Tibetan Buddhism was

flourishing in various regions in China.

"So from these stories we can see”, the Dalai

Lama continued, “that when the situation in China proper becomes more open,

with more freedom, then definitely many Chinese will find useful

inspiration from Tibetan Buddhist traditions” (Shambhala Sun, Archive, November 1996). In 1998, in an interview that

His Holiness gave the German edition of Playboy,

he quite materialistically says: “If we remain a part of China we

will also profit materially from the enormous upturn of the country” (Playboy, German edition, March 1998,

p. 44). The army of monks who are supposed to

carry out this ambitious project of a “Lamaization

of China” are currently being trained in Taiwan.

In 1997, the Kundun wrote to the Chinese

Party Secretary, Jiang Zemin, that he would like

to undertake a “non-political pilgrimage” to Wutaishan

in Shanxi

province (not in Tibet).

The most sacred shrine of the Bodhisattva Manujri, who from a Lamaist point of view is incarnated in the person of

the Chinese Emperor, is to be found in Wutaishan.

Thus for the lamas the holy site harbors the la, the ruling energy of the Chinese Empire. In preparing for

such a trip, the Kundun, who is a consistent thinker in

such matters, will certainly have considered how best to magically acquire

the la

of the highly geomantically significant site of Wutaishan.

The god-king wants to meet Jiang Zemin at this sacred location to discuss Tibetan

autonomy. But, as we have indicated, his primary motive may well be an

esoteric one. A “Kalachakra

ritual for world peace” is planned there. Traditionally, the Wutai

mountains are seen as Lamaism’s gateway to China. In the magical world

view of the Dalai Lama, the construction of a sand mandala

in this location would be the first step in the spiritual conquest of the

Chinese realm. Already in 1987, the well-known Tibetan lama, Khenpo Jikphun conducted a Kalachakra initiation in front of 6000 people.

He is also supposed to have levitated there and floated through the air for

a brief period (Goldstein, 1998, p. 85).

At the end of his critical book, Prisoners of Shangri-La, the Tibetologist and Buddhist Donald S. Lopez addresses the

Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s vision of “conquering” China specifically through the Kalachakra Tantra.

Here he discusses the fact that participants in the ritual are reborn as Shambhala warriors. “The Dalai Lama”, Lopez says, “may

have found a more efficient technique for populating Shambhala

and recruiting troops for the army of the twenty-fifth king, an army that

will defeat the enemies of Buddhism and bring the utopia of Shambhala, hidden for so long beyond the Himalayas, to

the world. It is the Dalai Lama’s prayer, he says, that he will some day give the Kalachakra initiation in Beijing” (Lopez,

1998, p. 207).

The “Strasbourg Declaration” (of June 15, 1988),

in which the Dalai Lama renounces a claim on state autonomy for Tibet if he

is permitted to return to his country, creates the best conditions for a

possible Lamaization of the greater Chinese

territory. It is interesting in this context that with the renouncement of political autonomy, the Kundun at the same time articulated a territorial

expansion for the cultural

autonomy of Tibet.

The border provinces of Kam and Amdo, which for centuries have possessed a mixed

Chinese-Tibetan population, are now supposed to come under the cultural

political control of the Kundun. Moderate circles in Beijing approve of the Dalai Lama’s

return, as does the newly founded Democratic Party of China under Xu Wenli.

Also, in recent years the numerous contacts

between exile Tibetan politicians and Beijing have not just been hostile,

rather the contacts sometimes awake the impression that here an Asian power play is at work behind closed

doors, one that is no longer easy for the West to understand. For example,

His Holiness and the Chinese successfully cooperated in the search for and

appointment of the reincarnation of the Karmapa,

the leader of the Red Hats, although here a Kagyupa

faction did propose another candidate and enthrone him in the West.

Since Clinton’s

visit to China

(in 1998) events in the secret diplomacy between the Tibetans in exile and

the Chinese are becoming increasingly public. On Chinese television Clinton said to Jiang

Zemin, “I have met the Dalai Lama. I think he is

an upright man and believe that he and President Jiang would really get on

if they spoke to one another” (Süddeutsche Zeitung, July 17, 1998). Thereupon, His Holiness

publicly admitted that several “private channels” to Peking

already existed which produce “fruitful contacts” (Süddeutsche Zeitung,

July 17, 1998). However, since 1999 the wind has turned again. The “anti

Dalai Lama campaigns” of the Chinese are now ceaseless. Owing to Chinese

interventions the Kundun has had to endure

several political setbacks throughout the entire Far

East. During his visit to Japan in the Spring of 2000 he

was no longer officially received. Even the Mayor of Tokyo (Shintaro Isihara), a friend

of the religious dignitary, had to cancel his invitation. The great hope of

being present at the inauguration of the new Taiwanese president, Chen Shui-Bian on May 20, 2000, was not to be, even though his

participation was originally planned here too. Despite internal and

international protest, South

Korea refused the Dalai Lama an entry

visa. The Xchinese even succeeded in excluding

the Kundun from the Millennium Summit of World

Religions held by the UN at the end of August 2000 in New York. The worldwide protests at this

decision remained quite subdued.

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama

and communism

The Kundun’s constant attestations that Buddhism and

Communism have common interests should also be seen as a further currying

of favor with the Chinese. One can thus read numerous statements like the

following from His Holiness: „The Lord Buddha wanted improvement in the

spiritual realm, and Marx in the material; what alliance could be more

fruitful?” (Hicks and Chogyam, 1990, p. 143); “I believe firmly there is common ground

between communism and Buddhism” (Grunfeld, 1996,

p. 188); “Normally I describe myself as half Marxist, half monk” (Zeitmagazin 1988, no. 44, p. 24;

retranslation). He is even known to have made a plea for a communist

economic policy: “As far as the economy is concerned, the Marxist theory

could possibly complement Buddhism...” (Levenson,

1992, p. 334). It is thus no wonder that at the god-king’s suggestion , the “Communist Party of Tibet” was founded.

The Dalai Lama has become a left-wing revolutionary even by the standards

of those western nostalgics who mourn the passing

of communism.

Up until in the eighties the Dalai Lama’s concern

was to create via such comments a good relationship with the Soviet Union, which had since the sixties become

embroiled in a dangerous conflict with China. As we have seen, even

the envoy of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Agvan Dorjiev, was a master at changing political fronts as

he switched from the Tsar to Lenin without a problem following the

Bolshevist seizure of power. Yet it is interesting that His Holiness has to

continued to make such pro-Marxist statements

after the collapse of most communist systems. Perhaps this is for ethical

reasons, or because China

at least ideologically continues to cling to its communist past?

These days through such statements the Kundun wants

to keep open the possibility of a return to Tibet under Chinese control. In

1997 in Taiwan

he explained that he was neither anti-Chinese nor anti-communist (Tibetan Review, May 1997, p. 14). He

even criticized China

because it had stepped back from its Marxist theory of economics and the

gulf between rich and poor is thus becoming ever wider (Martin Scheidegger, speaking at the Gesellschaft Schweizerisch

Tibetische Freundschaft

[Society for Swiss-Tibetan Friendship], August 18, 1997).

Are the Chinese interested in the Shambhala

myth?

Do the Chinese have an interest in the Kalachakra Tantra

and the Shambhala myth? Let us repeat, since time

immemorial China

and Tibet

have oriented themselves to a mythic conception of history which is not

immediately comprehensible to Americans or Europeans. Almost nobody here

wants to believe that this archaic way of thinking continued to exist, even

increased, under “materialistic” communism. For a Westerner, China today

still represents “the land of materialism” vis-à-vis Tibet as

“the land of spirituality”. There are, however, rare exceptions who avoid

this cliché, such as Hugh Richardson for example, who establishes the

following in his history of Tibet:

“The Chinese have ... a profound regard for history. But history, for them

was not simply a scientific study. It had the features of a cult, akin to

ancestor worship, with the ritual object of presenting the past, favorably

emended and touched up, as a model for current political action. It had to

conform also to the mystical view of China as the Centre of the World, the

Universal Empire in which every other country had a natural urge to become

a part … The Communists … were the first Chinese to have the power to

convert their atavistic theories into fact” (quoted by Craig, 1997, p.

146).

If it was capable of surviving communism, this

mythically based understanding of history will hardly disappear with it. In

contrast, religious revivals are now running in parallel to the flourishing

establishment of capitalist economic systems and the increasing

mechanization of the country. Admittedly the Han Chinese are as a people

very much oriented to material things, and Confucianism which has regained

respectability in the last few years counts as a philosophy of reason not a

religion. But history has demonstrated that visionary and ecstatic cults

from outside were able to enter China with ease. The Chinese

power elite have imported their religious-political ideas from other

cultures several times in the past centuries. Hence the Middle Kingdom is

historically prepared for such ideological/spiritual invasions, then up to

and including Marxist communism it has been seen, the Sinologist Wolfgang

Bauer writes, “that, as far as religion is concerned, China never went on

the offensive, never missionized, but rather the

reverse, was always only the target of such missionizations

from outside” (Bauer, 1989, p. 570). Nevertheless such religious imports

could never really monopolize the country, rather they all just had the one

task, namely to reinforce the idea of China as the center of the

world. This was also true for Marxist Maoism.

Let us also not forget that the Middle Kingdom

followed the teachings of the Buddha for centuries. The earliest evidence

of Buddhism can be traced back to the first century of our era. In the Tang

dynasty many of the Emperors were Buddhists. Tibetan Lamaism held a great

fascination especially in the final epoch, that of the Manchus.

Thus for a self-confident Chinese power elite a Chinese reactivation of the

Shambhala myth could without further ado

deliver a traditionally anchored pan-Asian ideology to replace a fading

communism. As under the Manchus, there is no need

for such a vision to square with the ideas of the entire people.

The Panchen

Lama

Perhaps the Dalai Lama’s return to Tibet is

not even needed at all for the Time Tantra to be

able to spread in China.

Perhaps the Chinese are already setting up their own

Kalachakra

master, the Panchen Lama, who is traditionally

considered friendly towards China.

„Tibetans

believe,” Edwin Bernbaum writes, „that the Panchen Lamas have a special connection with Shambhala,

that makes them unique authorities on the kingdom.” (Bernbaum,

1980, p. 185). In addition

there is the widespread prophecy that Rudra Chakrin, the doomsday general, will

be an incarnation of the Panchen Lama.

As we have already reported, the common history of

the Dalai Lama and the ruler from Tashi Lunpho (the Panchen Lama)

exhibits numerous political and spiritual discordances, which among other

things led to the two hierarchs becoming allied with different foreign

powers in their running battle against one another. The Panchen

Lamas have always proudly defended their independence from Lhasa. By and large they were more friendly with the Chinese than were the rulers in

the Potala. In 1923 the inner-Tibetan conflict

came to a head in the Ninth Panchen Lama’s flight

to China.

In

his own words he was „unable to live under these troubles and suffering” inflicted on him by Lhasa (Mehra, 1976, p. 45). Both he and the Dalai Lama had obtained weapons

and munitions in advance, and an armed clash between the two princes of the

church had been in the air for years. This exhausted itself, however, in

the unsuccessful pursuit of the fleeing hierarch from Tashilunpho

by a body of three hundred men under orders from Lhasa. The Thirteenth Dalai Lama was so

enraged that he denied the Buddhahood of the

fleeing incarnation of Amitabha, because this was selfish, proud, and ignorant.

It

had, together „with his sinful companoins, who

resembled mad elephants and followed wrong path,” made itself scarce (Mehra, 1976, p. 45).

In 1932 the Panchen Lama

is supposed to have planned an invasion of Tibet with 10,000 Chinese

soldiers to conquer the Land

of Snows and set

himself up as its ruler. Only after the death of the “Great Thirteenth” was

a real reconciliation with Lhasa

possible. In 1937 the weakened and disappointed prince of the church

returned to Tibet

but died within a year. His pro-China politics, however, still found

expression in his will in which he prophesied that “Buddha Amitabha’s

next incarnation will be found among the Chinese” (Hermanns,

1956, p. 323).

In the search for the new incarnation the Chinese

nation put forward one candidate and the Tibetan government another. Both

parties refused to recognize the other’s boy. However, under great

political pressure the Chinese were finally able to prevail. The Tenth Panchen Lama was then brought up under their influence.

After the Dalai Lama had fled in 1959, the Chinese appointed the hierarch

from Tashilunpho as Tibet’s nominal head of state.

However, he only exercised this office in a very limited manner and sometimes he

allowed to be carried away to make declarations of solidarity with the

Dalai Lama. This earned

him years of house arrest and a ban on public appearances. Even if the

Tibetans in exile now promote such statements as patriotic confessions, by

and large the Tenth Panchen Lama played either

his own or Beijing’s part. In 1978 he broke the vow of celibacy imposed

upon him by the Gelugpa order, marrying a Chinese

woman and having a daughter with her.

Shortly before his death he actively participated

in the capitalist economic policies of the Deng Xiaoping era and founded the

Kangchen

in Tibet

in 1987. This was a powerful umbrella organization that controlled a number

of companies and businesses, distributed international development funds

for Tibet,

and exported Tibetan products. The neocapitalist

business elite collected in the Kangchen was for the most part recruited from old

Tibetan noble families and were opposed to the

politics of the Dalai Lama, whilst from the other side they enjoyed the

supportive benevolence of Beijing.

As far as the Tibetan protest movement of recent

years is concerned, the Tenth Panchen Lama tried

to exert a conciliatory influence upon the revolting monks, but regretted

that they would not listen to him. “We insist upon re-educating the

majority of monks and nuns who become guilty of minor crimes [i.e.,

resistance against the Chinese authorities]" he announced publicly and

went on, “But we will show no pity to those who have stirred up unrest” (MacInnes, 1993, p. 282).

In 1989 the tenth incarnation of the Amitabha died. The Chinese made the funeral

celebrations into a grandiose event of state [!] that was broadcast

nationally on radio and television. They invited the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

to the burial which took place in Beijing,

but did not want him to visit Tibet afterwards. For this

reason the Kundun

declined. At the same time the Tibetans in exile announced that the Panchen Lama had been poisoned.

The political power play entered a spectacular new

round in the search for the eleventh incarnation. At first it seemed as if

the two parties (the Chinese and the Tibetans in exile) would cooperate.

But then there were two candidates: one proposed by the Kundun and one by Beijing. The latter

was enthroned in Tashi Lunpho.

A thoroughly power-conscious group of pro-Chinese lamas carried out the

ceremonies, whilst the claimant designated by the Dalai Lama was sent home

to his parents amid protests from the world public. At first, Dharamsala spoke of a murder, and then a kidnapping of

the boy.

All of this may be considered an expression of the

running battle between the Tibetans and the Chinese, yet even for the

Tibetans in exile it is a surprise how much worth the Chinese laid on the

magic procedure of the rebirth myth and why they elevated it to become an

affair of state, especially since the upbringing of the Dalai Lama’s

candidate would likewise have lain in their hands. They probably decided on

this course out of primarily pragmatic political considerations, but the

magic religious system possesses a dynamic of its own and can captivate

those who use it unknowingly. A Lamaization of China with

or without the Dalai Lama is certainly a historical possibility. In October

1995 for example, the young Karmapa was guest of

honor at the national day celebrations in Beijing and had talks with important

heads of the Chinese government. The national press reported in detail on

the subsequent journey through China which was organized for

the young hierarch by the state. He is said to have exclaimed, “Long live

the People’s Republic of China!”

(Tibetan Review, November 1994,

p. 9).

What a perspective would be opened for the

politics of the Kalachakra deities if they were able to anchor

themselves in China

with a combination of the Panchen and Dalai Lamas

so as to deliver the foundations for a pan-Asian ideology! At last, father

and son could be reunited, for those are the titles of the ruler from Tashilunpho (the father) and the hierarch from the Potala (the son) and how they also refer to one

another. Then one would have taken on the task of bringing the Time Tantra to the West, the other of reawakening it in its

country of origin in Central Asia. Amitabha and Avalokiteshvara,

always quarreling in the form of their mortal incarnations, the Panchen and the Dalai Lama, would now complement one

another — but this time it would not be a matter of Tibet, but China, and

then the world.

The Communist Party of China

The Communist Party of China’s official position

on the social role of religion admittedly still shows a Marxist-Leninist

influence. “Religious belief and religious sentiments, religious ceremonies

and organizations that are compatible with the corresponding beliefs and

emotions, are all products of the history of a society.

The beginnings of religious mentality reflect a

low level of production... “, it says in a government statement of

principle, and the text goes on to say that in pre-communist times religion

was used as a means “to control and still the masses” (MacInnes,

1993, p. 43). Nevertheless, religious freedom has been guaranteed since the

seventies, albeit with some restrictions. Across the whole country a

spreading religious renaissance can be observed that, although still under

state control, is in the process of building up hugely like an underground

current, and will soon surface in full power.

All religious orientations are affected by this —

Taoism, Chan Buddhism, Lamaism, Islam, and the various Christian churches. Officially , Confucianism is not considered a faith but

rather a philosophy. Since the Deng era the attacks of the Great Proletarian

Cultural Revolution upon religious representatives have been

self-critically and publicly condemned. At the moment, more out of a bad

conscience and touristic motives than from religious fervor, vast sums of

money are being expended on the restoration of the shrines destroyed.

Everyone is awaiting the great leap forwards in a

religious rebirth of the country at any moment. “China’s tussle with the Dalai

Lama seems like a sideshow compared to the Taiwan crisis” writes the

former editor of the Japan Times Weekly,

Yoichi Clark Shimatsu, “But Beijing is waging a

political contest for the hearts and minds of Asia's

Buddhists that could prove far more significant than its battle over the

future democracy in Taiwan”

(Shimatsu, HPI 009).

It may be the result of purely power political

considerations that the Chinese Communists employ Buddhist constructions to

take the wind out of the sails of the general religious renaissance in the

country via a strategy of attack, by declaring Mao Zedong to be a

Bodhisattva for example (Tibetan

Review, January 1994, p. 3). But there really are — as we were able to

be convinced by a television documentary — residents of the eastern

provinces of the extended territory who have set up likenesses of the Great

Chairman on their altars beside those of Guanyin and Avalokiteshvara,

to whom they pray for help in their need. A mythification

of Mao and his transformation into a Bodhisattva figure should become all

the easier the more time passes and the concrete historical events are

forgotten.

There are, however, several factions facing off in

the dawning struggle for Buddha’s control of China. For example, some of the

influential Japanese Buddhist sects who trace their origins to parent

monasteries in China

see the Tibetan clergy as an arch-enemy. This too has its historical

causes. In the 13th century and under the protection of the

great Mongolian rulers (of the Yuan dynasty), the lamas had the temples of

the Chinese Buddhist Lotus sect in southern China razed to the ground. In

reaction the latter organized a guerilla army of farmers and were

successful in shaking off foreign control, sending the Tibetans home, and

establishing the Ming dynasty (1368). “This tradition of religious

rebellion”, Yoichi Clark Shimatsu writes, “did

not disappear under communism. Rather, it continued under an ideological

guise. Mao Zedong's utopian vision that drove

both the Cultural Revolution and the suppression of intellectuals in

Tiananmen Square bears a striking resemblance with the populist Buddhist

policies of Emperor Zhu Yuanthang, founder of the

Ming Dynasty and himself a Lotus Sect Buddhist priest” (Shimatsu,

HPI 009).

Many Japanese Buddhists see a new “worldly” utopia

in a combination of Maoist populism, the continuation of Deng Xiaoping's

economic reforms, and the familiar values of (non-Tibetan) Buddhism. At a

meeting of the Soka Gokkai

sect it was pointed out that the first name of the Chinese Premier Li Peng was “Roc”, the name of the mythic giant bird that

protected the Buddha. Li Peng answered allegorically

that in present-day China

the Buddha “is the people and I consider myself the guardian of the people”

(Shimatsu, HPI 009). Representatives of Soka Gokkai also interpreted

the relationship between Shoko Asahara and the

Dalai Lama as a jointly planned attack on the pro-Chinese politics of the

sect.

Like the Tibetans in exile ,

the Chinese know that power lies in the hands of the elites. These will

decide which direction future developments take. It is doubtful whether the

issue of national sovereignty will play any role at all among the Tibetan

clergy should they be permitted to advance into China with the toleration and

support of the state. Since the murder of King Langdarma,

Tibetan history teaches us, the interests of monastic priests and not those

of the people are preeminent in political decisions. This was likewise true

in reverse for the Chinese Emperor. The Chinese ruling elite will in the

future also decide according to power-political criteria which religious

path they will pursue: “Beijing

clearly looks to a Buddhist revival to fill the spiritual void in the Asian

heartland so long as it does not challenge the nominally secular

authorities. Such a revival could provide the major impetus into the

Pacific century. Like all utopias, it could also be fraught with disaster”

(Shimatsu, HPI 009).

The West, which has not reflected upon the

potential for violence in Tantric/Tibetan Buddhism or rather has not even

recognized it, sees — blind as it is — a pacifist and salvational

deed by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama in the spread of Lamaism in China. The

White House Tibet expert, Melvyn Goldstein, all but demands of the Kundun that he return to Tibet. In

this he is probably voicing the unofficial opinion of the American

government: “If he [the Dalai Lama] really wants to achieve something,”

says Goldstein, “he has to stop attacking China on the international stage, he has to return and publicly accept the

sovereignty over his home country” (Spiegel

16/1998, p. 118).

Everything indicates that this will soon happen,

and indeed at first under conditions dictated by the Chinese. In his

critique of the film Kundun, the journalist Tobias Kniebe writes that, “As little real power as this man

[the Dalai Lama] may have at the moment — as a symbol he is unassailable

and inextinguishable. The history of nonviolent resistance is one of the

greatest, there is, and in it Kundun [the film] is a kind of prelude. The actual film,

which we are waiting for, may soon begin: if an

apparently impregnable, billion-strong market is infiltrated by the power

of a symbol [the Dalai Lama] whose evidence it is unable to resist for

long. If this film is ever made, it will not be shown in the cinemas, but

rather on CNN” (Süddeutsche Zeitung,

March 17, 1998). Kniebe and many others thus await

a Lamaization of the whole Chinese territory.

A wild speculation? David Germano,

Professor of Tibetan Studies in Virginia, ascertained on his travels in

Tibet that “The Chinese fascination with Tibetan Buddhism is particularly

important, and I have personally witnessed extremes of personal devotion

and financial support by Han Chinese to both monastic and lay Tibetan

religious figures [i.e., lamas] within the People's Republic of China”

(Goldstein, 1998, p. 86).

Such a perspective is expressed most clearly in a

posting to an Internet discussion forum from April 8, 1998: “"Easy, HHDL [His

Holiness the Dalai Lama]", it says, “can turn the people of Taiwan and China

[into] becoming conformists of Tibetan Buddhism. Soon or later, there will

be the Confederate

Republics of Greater

Asia. Republic

of Taiwan, People's

Republic of China,

Republic of Tibet, Mongolia Democratic Republic,

Eastern Turkestan Republic,

Inner Mongolian Republic,

Nippon,

Korea ...

all will be parts of the CROGA. Dalai Lama will be the head of the CROGA”

(Brigitte, Newsgroup 10).

But whether the Kundun returns home to the

roof of the world or not, his aggressive Kalachakra ideology is not a

topic for analysis and criticism in the West, where religion and politics

are cleanly and neatly separated from one another. The despotic idea of a

world ruler, the coming Armageddon, the world war between Buddhism and

Islam, the establishment of a monastic dictatorship, the hegemony of the

Tibetan gods over the planets, the development of a pan-Asian, Lamaist major-power politics — all visions which are

laid out in the Kundun’s

system and magically consolidated through every Kalachakra initiation — are