|

History

Happenings (October 2011)

Totalitarian Temptations

Professor Andrei Znamenski,

talks about his latest book,

Red Shambhala,

with Professor Guiomar Dueñas-Vargas

Dueñas-Vargas:

Professor Znamenski, What is Shambhala?

Is it a prophecy? Is it a geographic place for Buddhism? Is it a land of

plenty and spiritual enlightenment? Is it a violent and aggressive creed? Would

you please tell us what is the Shambhala of your

book?

Znamenski: To make a long story short, Shambhala was a Buddhist prophecy that had emerged in

the Early Middle Ages. When Muslims had advanced into Afghanistan and Northern

India, they dislodged the Buddhists from these areas, and they

had to find a safe haven somewhere. So they came up with a spiritual

resistance prophecy that was identified with a land, a utopian land, a kind

of a Buddhist paradise, where the members of this faith would be free to

live and worship without been harassed by the “barbarians” whom Sanskrit

sources called “Mlecca people” or, in other

words, the people of Mecca. The legend claimed that somewhere in the North

there was a mysterious country, a land of plenty where people lived 900

years, where they were rich and had houses where roofs were clad in gold,

and where nobody suffered, and of course, where the Buddhist religion

existed in its pure form and so forth.

Dueñas-Vargas:

But Shambhala involves, as well, a concept of

holy war. Is that true?

Znamenski: By the way, in original

Buddhism there was no concept of Paradise.

This concept emerged as a result of encounters with the Muslim world. The

prophecy also claimed that when the true faith (read Buddhism) would be in

danger, the king of Shambhala named Rudra Chakrin would come with

a huge army and crash the enemies of the faith. So, it is a concept of a

holy war, pure and simple. Many people are not aware that such concept

existed in Tibetan Buddhism. The Shambhala

prophecy lingered on, and in modern time was sometimes engaged, when the

Mongol-Tibetan world felt threatened by outsiders. At the same time, Shambhala was also understood as an internal war

against one’s own inner demons. It was an aspiration for a spiritual

perfection. In the course of time, the former, the holy war part, gradually

disappeared and the latter one became more relevant. A nice example for some

other religions to follow. Don’t you agree?

Dueñas-Vargas:

Yes, in this case, Tibetan Buddhism might have served as a role model for

other world religions. Yet, your book deals more with the former, the holy

war part of the prophecy. Correct?

Znamenski: Yes, the time I am writing

about, the 1920s and the 1930s, was a period of troubles and dramatic

changes for the Tibetan-Mongol world. The Manchu Empire in China

collapsed in 1911 following by the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917. The

entire political landscape of Eurasia

became filled with ethnic, religious, and class conflicts. That was when Shambhala and various sister prophecies resurfaced in

Inner Asia as apocalyptic legends that helped local populations to deal

with reality.

Dueñas-Vargas:

In your book you mention how Shambhala and other

related Asian prophecies were used by outsiders, especially by the

Bolsheviks of Red Russia. Tell us more about it.

Znamenski: It’s an excellent

question. See,

originally Bolsheviks, when they came to power in 1917, firmly expected

that Communism would win first in the most advanced Western countries,

where organized socialist movement had a long history. But, unfortunately

for them, Western workers didn’t respond to the Bolshevik gospel of

world-wide Communist revolution. The only success they had was among Asian

people, where the Bolsheviks were able to plague themselves into local

national liberation movements. That was how they became interested in

latching on Mongol-Tibetan prophecies and linking them to Communism. The

Communist International, an organization created in 1919 to promote the

world-wide revolution, established a Mongol-Tibetan Section to draw the

local nomads, peasants and junior lama monks to Communism. For example, in Mongolia,

Bolshevik fellow-travellers explained to the populace that Communism was

actually a fulfillment of legendary Shambhala.

Dueñas-Vargas:

Yes, as well-explained in the book, they were extremely ambitious!

Znamenski: Yes, quite ambitious. You have

to understand that at that time early Bolsheviks lived by a revolutionary

romanticism. They expected the coming of the world-wide revolutionary fire

would cleanse the whole world from oppression. Non-Western colonial

nationalities were viewed as allies in this fight against imperialist West.

At one point, Leon Trotsky, one of the chief leaders of the Russian

revolution, even suggested that the Bolsheviks send a cavalry division to India, straight across Inner Asia, and

liberate entire Asia. In my book I

describe another curious episode when Red Russia sent an expedition that

was disguised as a group of Buddhist pilgrims and that tried to sway the

13th Dalai Lama to the Bolshevik side.

Dueñas-Vargas:

Well, in your book you profile a group of very strange characters that

include not only people on the Left but also on the Right side. Can you elaborate?

Znamenski:

Absolutely. My book actually represents a series of biographical essays

that are linked together because all my characters were somehow connected

with each other. Let’s start with the Bolsheviks

and their fellow travellers.

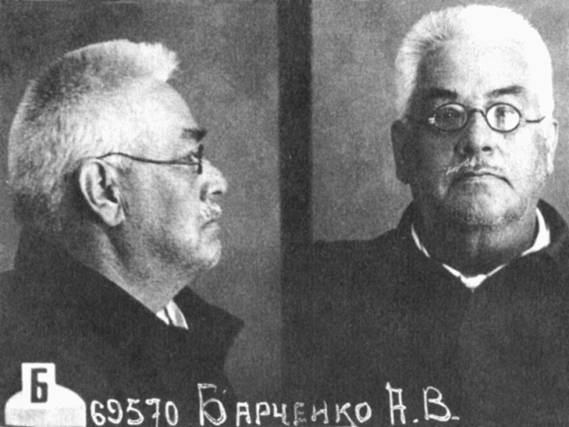

Alexander Barchenko

The

first one is Alexander Barchenko, an occult

writer from St. Petersburg,

and his Bolshevik secret police patron Gleb Bokii, the master of codes, who was actually one of the

spearheads of the Communist Revolution 1917. At some point, Bokii decided to use Tibetan Buddhism and its spiritual

techniques to change the minds of the people, in other words, to help

engineer the new communist human being.

Dueñas-Vargas:

To engineer?

Znamenski: Yes, he and some other Bolshevik

intellectuals were upset that the revolution did not change the human

nature, and they were playing with an idea of transforming the human beings

in order to make them better. One of the chapters of the book carries a

peculiar title “The Engineer of the Human Soul.” In fact, in the 1920s,

unlike later times, there were lots of social experiments in Red Russia,

crazy experiments. It was like the United States in 1960s. There

were communes, different types of left groups, avant-garde artists, poets,

and anarchists.

Gleb Bokii

Dueñas-Vargas:

I haven´t brought a question about Bokii’s attempt to use the Buddhist tantra

and naturism.

Znamenski: Well, we are not going now

there because, it’s something that readers might learn from the book on

their own.

Dueñas-Vargas:

Another two major characters are a Russian American painter Nicholas

Roerich and his wife Helena. They were also interested in Shambhala. They wanted to go to Tibet and

retrieve Tibetan wisdom. Was their goal purely spiritual?

Nicholas Roerich

Znamenski: Not really. This ambitious

couple nourished a megalomaniac idea to build in the heart of Asia a Tibetan Buddhist utopia (they called it the

Sacred Union of the East) that would throw light to the rest of the

humankind. At one point, in 1926, they tried to flirt with Communism

because Helena and Nicholas Roerich believed that since the Shambhala legend said salvation would come from the

North, they wanted to use Red Russia in their grand scheme. In fact,

Roerich went to Tibet,

posing as reincarnated Dalai Lama and pretended to dislodge the existing

13th Dalai Lama. Red Russia refused to wholeheartedly support such a

reckless project and the couple became frustrated with the Bolsheviks.

Dueñas-Vargas:

They were living their own fantasy. Weren’t they?

Znamenski: Yes, pretty much. It was a

geopolitical fantasy that, by the way, perfectly fit the context of the

time, which historian Eric Hobsbawm called, the

age of extremes. When they parted with the Bolsheviks, the Roeriches began courting American sponsors. Among them

we find a rich currency speculator Louis Horch

and future FDR’s vice president Henry Wallace, who in fact later sponsored

the Roerich’s second expedition Asia.

Dueñas-Vargas:

This is unbelievable. Now, let’s turn to another peculiar character, the

“Bloody Baron,” a right-wing opponent of the Bolsheviks.

Roman von Ungern Sternberg

Znamenski:

Roman von Ungern Sternberg, a Baltic German baron, a descendant of Teutonic knights.

Dueñas-Vargas:

Yes, he was a very ruthless character.

Znamenski: Pretty much an evil character,

and in fact one predecessors of the Nazis. This

baron who acquired such notoriety in Inner Asia in 1920-1921 belonged to

the elite of Old Russia. After the 1917 revolution, he became obsessed with

a grand project of restoring monarchies from China

and Russia to Germany and

Austro-Hungary. Eventually he escaped from the Bolsheviks because they had

a popular support and he didn’t and, while escaping southward, hijacked Mongolia. He

milked for a while national sentiments of Mongols and helped them to

liberate their country from the Chinese. And that is why he lost that

country. The Mongols, who at first glorified him and declared him a

reincarnation of Mahakala, a god-protector of

Tibetan Buddhism, suddenly realized that the baron simply had his own

agenda that was utterly strange to them. For example, trapped in the world

of his European xenophobia, Ungern was talking to

them about the so-called Jewish conspiracy, which sounded quite bizarre to

the nomads who asked themselves a question, “What’s going on?”

Dueñas-Vargas:

He was out of place.

Znamenski: Exactly.

Dueñas-Vargas:

Your primary sources are impressive. How and where did you find these

documents?

Znamenski: I became interested in the

topic about seven years ago, and began reading relevant literature while,

simultaneously gathering primary sources in archives of Moscow, New York,

and St. Petersburg, but the actual writing took me two years, from 2008 to

2009. Quest Books, my publisher, gave me an advanced contact in 2008 and

specified that the book should have no more than 80,000 words, which is

about 300 pages; an editor explained to me that anything that goes beyond

that will simply scare people away. This helped to discipline my mind.

Dueñas-Vargas:

Thank you for sharing with us the information about your most recent book,

and good luck with feature projects.

Znamenski: Thank you too. I wanted to add

that the book is available on amazon.com, where I also created my author’s

page - a nice amazon feature that allows authors

to profile their books like, for example, posting video clips that sample

book chapters.

The Book – Videos – Interviews – Reviews:

www.trimondi.de/EN/Red_Shambhala.htm

Vita:

Historian, anthropologist and

translator, Andrei Znamenski was a resident

scholar at the Library of Congress, and then a foreign visiting professor

at Hokkaido University, Japan. He has taught

various courses at The University of Toledo, Alabama State University, and

the University

of Memphis. Among them are World Civilizations,

Russian history, and the History of Religions.

Znamenski’s

major fields of interests include the history of Western esotericism, Russian history as

well as indigenous religions of

North America, Siberia, Inner Asia, particularly Shamanism and

Tibetan Buddhism. Znamenski lived and traveled extensively in Alaska,

Siberia, and Japan. His field and archival research among Athabaskan Indians in Alaska

and native people of the Altai (Southern Siberia)

resulted in the book Shamanism and Christianity: Native Responses to

Russian Missionaries (1999) and Through Orthodox Eyes: Russian Missionary Narratives of Travels

to the Dena'ina and Ahtna (2003).

After this,

Znamenski became interested in the cultural

history of Shamanism. Endeavoring to answer why shamanism became so popular

with Western spiritual seekers since the 1960s, he wrote The Beauty of the Primitive: Shamanism

and Western Imagination (2007) and edited the three-volume

anthology Shamanism: Critical

Concepts (2004). Simultaneously,

he continued to explore shamanism of Siberian indigenous people, traveling to the Altai and surrounding areas, which led

to the publication of Shamanism in

Siberia (2003). Between 2003 and 2004, he resided in Japan, where along with his

Japanese colleague, Professor Koichi Inoue, Znamenski

worked with itako,

blind female healers and mediums from the Amori

prefecture.

|