|

CRITICAL

FORUM KALACHAKRA

Buddhists, Occultists and

Secret Societies in Early Bolshevik Russia: an interview with

Andrei Znamenski

Andrei Znamenski is the author of Red Shambhala:

Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia, published by Quest

Books. Shambhala, a mythical, heaven-type land in

Tibetan Buddhism, was created during a period of conflict between Buddhists

and Muslims in Asia, and appears to have

been partly modeled on Islamic doctrine. As Znamenski

himself points out, the Buddhists had no conception of a paradise before

this. Shambhala, which originally had both

spiritual and martial qualities, may also have been modeled on the Islamic

idea of the inner and outer Jihad. With Shambhala,

though, the martial side eventually disappeared, and the myth entered the

Western imagination with a number of later nineteenth and early twentieth

century occult and mystical movements. In 1933, British author James Hilton

popularized the notion of Shambhala, which he

renamed Shangri-La. In Red Shambhala – the first

and only authoritative book on the subject – Znamenski

explores the origins of the Shambhala myth, as

well its appropriation by Western occult movements, spiritualists,

Bolsheviks, and the “bloody baron” Roman von Ungern-Sternberg.

AZ: Let

me first give you a few ideas about how Red Shambhala

came about. When I was writing my previous book, The Beauty of the

Primitive, about shamanism and the Western imagination, I stumbled upon

some interesting information that in the Soviet Union of the 1920s there

was a secret lab where Soviet secret police was conducting experiments with

Buddhist lamas, shamans, hypnotists, and all kinds of spiritual experts.

The goal was to use this knowledge to spearhead the cause of communism.

Then I found

information that this lab was part of so-called Special Section of the

Soviet secret police. The head of the Special Section was Gleb Bokii. This

hereditary aristocrat, whose ancestor had been granted nobility by the Ivan

the Terrible, was an interesting man. First of all, Bokii

was one of the spearheads of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, and afterwards

became one of the leaders of the secret police in Red Russia. An active

member of the Marxist underground, he spent much of his life before 1917 in

czarist prisons and exile. At the same time, he dabbled in occult knowledge

and mysticism. In the early 1920s, he stumbled upon a writer and

occultist named Alexander Barchenko and became

close friends with him. Eventually, Bokii put Barchenko in charge of that secret lab.

Barchenko was

very much interested in the Agartha legend – a

Western occult myth about a legendary country that exists underground and

preserves high knowledge. French occult writer Alexandre

Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, who popularized this

legend and whom Barchenko held in a high esteem,

argued that this mystic country was located somewhere in Inner Asia.

Later, when in 1918 Barchenko learned from Mongol

and Tibetan visitors to Bolshevik Russia about the Shambhala

legend – a story about the Tibetan-Buddhist spiritual paradise and abode of

high wisdom – he came to conclusion that the legendary underground land and

the mythological country from the Tibetan-Buddhist tradition, is the same

thing. In fact, in his talks he frequently used expression Shambhala-Agartha. Bokii with

whom Barchenko shared this knowledge became very

much excited and together they began planning an expedition to Tibet to

access this country and to use its “ancient science” to help the cause of

Communism. This emphasis on science was not an accidental

remark. Both Barchenko and Bokii thought about their occult quest as an attempt to

locate some hard scientific knowledge (mind-bending techniques, mental

waves, the sound effect of mantras and so on) that was hidden in the heart

of Asia and needed to be unlocked.

PoS: You mentioned Shambhala.

This is a Tibetan Buddhist legend, but it entered into Western culture with

Theosophy and other New Age and esoteric movements. Can you tell me a bit

about it?

AZ: To make a long

story short, Shambhala was a Buddhist prophecy

that had emerged in the Early Middle Ages. When Muslims had advanced into Afghanistan and Northern

India, they dislodged the Buddhists from these areas, and they

had to find a safe haven somewhere. So they came up with a spiritual

resistance prophecy that was identified with a land, a utopian land, a kind

of a Buddhist paradise, where the members of this faith would be free to

live and worship without been harassed by the “barbarians” whom Sanskrit

sources called “Mlecca people” or, in other

words, the people of Mecca. The legend claimed that somewhere in the North

there was a mysterious country, a land of plenty where people lived 900

years, where they were rich and had houses where roofs were clad in gold,

and where nobody suffered, and of course, where the Buddhist religion

existed in its pure form and so forth.

In original

Buddhism there was no concept of Paradise.

This concept emerged as a result of encounters with the Muslim world. The

prophecy also claimed that when the true faith (read Buddhism) would be in

danger, the king of Shambhala named Rudra Chakrin would come with

a huge army and crash the enemies of the faith. So, it is a concept of a

holy war, pure and simple. Many people are not aware that such concept

existed in Tibetan Buddhism. The Shambhala

prophecy lingered on, and in modern time was sometimes engaged, when the

Mongol-Tibetan world felt threatened by outsiders. At the same time, Shambhala was also understood as an internal war

against one’s own inner demons. It was an aspiration for a spiritual

perfection. In the course of time, the former, the holy war part, gradually

disappeared and the latter one became more relevant.

Let’s go back to Bokii and Barchenko. The

1920s in Soviet Russia was a very interesting time, when some Bolsheviks

and their fellow-travelers were involved in a lot of social and cultural

experiments. The Red dictatorship hadn’t established itself firmly yet, so

there still remained some outlets where people could express themselves

artistically and culturally: Avant-garde art, nudism, naturism, feminism,

some spirituality practices and communes. Barchenko

himself set up a society called the United Labor Brotherhood, modeled after

George Gurdjieff’s brotherhood. The goal was to

use sacred knowledge to promote communal lifestyle based on high moral

standards and spirituality and eventually make people nobler.

Bokii

and Collegium

When I was learning

all this information, I completed my first book. Then I decided to dig in

further to find out what it was all about. Eventually I discovered that

some other Russian writers had written about it. One St. Petersburg writer, Alexandre Andreyev, had written about the Bolshevik

quest for Shambhala. So I read his book,

and I also went to the archives in Moscow.

I also found some interesting documents in the Moscow Archive of

Socio-Political History about how some Buddhist communities in the early

Soviet Union, in the 1920s, tried to find a common language with the

Bolsheviks, and how the Bolsheviks had tried to use the Buddhists to

spearhead the communist cause in Mongolia,

Tibet, and Western China.

Incidentally, the

Communist International (or Comintern), which was

an organization created by the Bolsheviks to promote the gospel of

Communism all over the earth, established a special Mongol-Tibetan Section

that was assigned to channel the Marxist secular prophecy to the masses of

Inner Asia by using indigenous prophecies and traditional culture.

One of the

interesting figures here was Agvan Dorzhiev, a tutor for the thirteenth Dalai Lama – the

predecessor of the present day Dalai Lama. Dorzhiev

became a Tibetan ambassador in Soviet Russia. He tried to build bridges

between Red Russia and Tibet.

The assumption was that Soviet Russia would be able to guarantee the

independence of Tibet.

And the theological justification for this was the Shambhala

legend, which said that in a time of trouble salvation would come from the

north.

Then I found

information about this crazy, bloody White baron, who tried to hijack Mongolia in

1920 – Roman von Ungern-Sternberg. There are some

interesting documents, showing that he also wanted to use the Shambhala prophesy to spearhead his own cause. For

example, when the Bolsheviks seized the papers of his Asian Cavalry

Division, they found a detailed translation of the Shambhala

prophecy into Russian. Obviously, the baron might have been toying somehow

with as an idea that he could act as that Rudra Chakrin, the legendary king of Shambhala,

who was coming to save the Buddhist world from infidels.

And of course I

found out that Russian painter and émigré in the USA Nicholas Roerich was

also attracted to this legend, in the same way. In fact, Roerich, who was

well familiar with Dorzhiev and Ungern activities, was afraid to come too late to use

this potent prophecy. Hence, he rushed to Inner Asia in 1923.

Mongol commissars with

Lenin sacred scroll

PoS: Why do you think so many people were

interested in this legend at that time? Was there something that had

sparked this internationally?

AZ: The more I

think about it the more I realize that it was about the time itself – the

1920s and the 1930s. Remember that German word zeitgeist, the spirit of the

times. That is what it was all about. At first, there was such horrible

disaster as the First World War. Then the Great Depression came. People had

this feeling that the whole world was coming to an end. In such times, both

the populace and the elites naturally rush to entrust their fate to various

ideological and political saviors (for example, Mussolini, Stalin, Hitler,

and Roosevelt), who promise welfare and

security for everybody. That is why we have all those dictatorships

growing all over the world at that time. If you look at a map of the world

from the 1920s to the 1940s, you may count on your fingers those few

countries that remained more or less democratic: England,

Sweden, and the United States.

By the way, even the United

States under FDR clearly moved toward

centralized state. If it had not been for those checks and balances in the

US Government, FDR, a power-hungry Machiavellian, would have taken

advantage of the crisis situation and with all his prices and wages

regulations and back-to-land philosophy would have produced something

resembling Italian fascism.

So I think longing

for the “great father” was a way to resolve the crisis. Among the people of

that time there was an expectation that a savior should come – a

Stalin-type figure, or a Hitler-like prophet, or FDR-type person –

benevolent and wise enlightened master. The people wanted to find a sort of

master key – the ultimate solution to resolve all the problems in the

world. So these dominant sentiments certainly affected the fringe figures

we are talking about here: Roerich, Dorzhiev, Bokii and Barchenko, and Ungern. Prophesies from the world of Tibetan Buddhism

responded to their spiritual and ideological expectations. After all, they

were people of their time.

PoS: I thought that after the October

Revolution that the Bolsheviks pretty much had their way, but it was a lot

freer and they weren’t able to regulate people as much, then?

AZ: Yes and no.

See, some writers and scholars who peddled the 1920s as some sort of humane

period in the history of Bolshevism were to some extent driven by the idea

to save the idea of Socialism that was crumbling in the 1970s and the

1980s. Some of these writers even hinted that the 1920s was a lost

alternative – a trajectory that, if followed, could have led to “socialism

with a human face” and all that stuff. But the real reason why

there was a temporary liberalization was because the Bolsheviks at first

had tried to impose so-called “war communism” – they had tried a cavalier

attack by canceling money, destroying the banking system, trade, and

putting the entire society in barracks. And it ruined the entire economy.

So Lenin made it clear to his comrades: we might lose the entire country.

He literally begged his comrades to temporarily make a strategic

retreat. So the Bolsheviks willy-nilly stopped confiscating grain

from peasants and restored some market at least for peasants to work freely

on their homesteads, which eventually helped to feed the starving country.

They also opened limited outlets to private enterprise. But when you

release some of these forces of course it brings up certain cultural

liberalization.

So that is why

there was some limited cultural liberalization. And there were also

some independent groups. Of course the secret police controlled all of

them. Their members informed on each other. By the way, that is when this

practice was introduced on a nationwide basis in Soviet Russia. The

Bolsheviks knew that they had to allow partial liberalization, but they

were afraid they might lose the country ideologically, so they started to

encourage people to inform on each other.

From documents that

I read I have this hint that Barchenko was

actually recruited as an informer, to inform on the other people who were

in the occult, New Age-type spirituality. He delivered reports about other

people. He wasn’t actually trusted by many spiritual seekers in the St. Petersburg

esoteric circles, because they suspected him of being a secret police

snitch. But he was not the only one. A lot of people were encouraged to do

this. It was part of the game.

PoS: So the Bolsheviks as a whole didn’t look

very favorably on this New Age spiritual movement.

AZ: No, no. In fact

in 1929 they started to crack down on this. It was allowed during the 1920s

because the dictatorship did not have yet a total grip on the country and

because there were still some pre-1917 cosmopolitan Bolshevik types like Bokii, who played with this or tolerated it. There was

another person, Anatoly Lunacharski, the

commissar of Enlightenment – it’s like the Secretary of Education. He

promoted the idea that Communism should be treated as a new religion.

He and those who agreed with him called themselves “God-builders.” And if

you look closely, Communism is indeed a secular prophesy. Lenin, Stalin and

the rest of the gang never wanted people to think this way. For them

Communism was high science through and through – the science that harnessed

the laws of history. But Lunacharski

actually wanted to promote this idea that Communism was a new religion of

the oppressed masses and to tell the populace that instead of God we have

Karl Marx, and instead of the Ten Commandments we have certain communist

commandments. There were some others who wanted to link Communism to

spirituality. But Stalin shut all this down in 1929.

PoS: So what happened to the spiritual

practitioners? Were they just told to not do it? Or were they sent to the

gulags? Or?

AZ: Well many of

them were sent to concentration camps. It’s clear from documents I am

familiar with that in the late 1920s, they were informing on each other.

Doing these esoteric things, the occult, but informing on each other at the

same time. In 1929 they were sent to labor camps for three or five years.

Many of them were released in the early 1930s. But during the period of the

Great Terror, 1937-1938, they were thrown into prison again. And many of

them were either executed or died in labor camps from hunger, disease, and

hard labor.

Dorzhiev, the builder of Buddhist

Theocracy in Asia

But the secret

police – who were issued quotas about how many people they should arrest –

they even tried to manufacturer some occult groups, so that they could

report to their bosses that they had uncovered an occult, anti-Soviet

group. Because if one didn’t catch enough anti-Soviet elements, he could

not be promoted or, worse, one could become a victim himself. A large set

of declassified secret police documents that I recently read – it is about

so-called Asian Brothers, the last (1940-1941) Freemason police case in Red

Russia – is a pathetic and surreal story. In the 1920s and the early 1930s,

manufacturing their cases, Soviet secret police at least dealt with real

practicing occultists and intellectuals interested in mysticism. This

particular case under the name of “Obscurantists”

was manufactured out of a thin air from the beginning to the end and

involved four persons who completely stopped toying with occult at the end

of the 1920s, and three of whom, on top of this, were paid secret police

informers.

I guess by that

time the regime ran out of occultists to be arrested. Officers wrote

the scripts of testimonies for the four accused persons and tried to force

them to endorse these documents. Interestingly, one of them, certain

Eugene Tager, a former anarchist who toyed with

Freemasonry in the 1920s, was delivered from a Kolyma

labor camp where he was doing his time for his esoteric “sins” to play a

role in this new case. Yet the man firmly stood his ground. He was

repeatedly beaten by his investigator but never testified against himself

or other people and completely refused to cooperate. Moreover, the guy had

a nerve to file a complaint against his investigators. So they gave up on

him and sent him back to Siberia to finish

his sentence.

The other two,

Boris Astromov and Sergei Polisadov,

very active Freemasons in the 1920s and simultaneously seasoned police

informers who earlier gave to the police a lot of “human material” to work

with, now realized that their turn had come and refused to cooperate

too. Essentially, the entire case was based on testimonies of Vsevolod Belustin, a former

head of the Rosicrucian order in Russia and also a police

informer, the only one who cracked and agreed to testify against himself and others. The investigators contemplated to

construct a case about a secret anti-Soviet Freemason organization “Asian

Brothers” that spied for England

and that involved those four along with a dozen of Orientalists

from Soviet Academy of Sciences. Although Belustin

cooperated, coauthoring his testimonies with his investigators, to his

credit, many of the names of “Freemasons” he mentioned belonged to

long-deceased people, including Sergei Oldenburg, a famous Russian student

of Hinduism and Buddhism. Although the three former Freemasons/informers

were sentenced to several years of labor camps, secret police fiction

writers could not produce a sound case and had to archive the file.

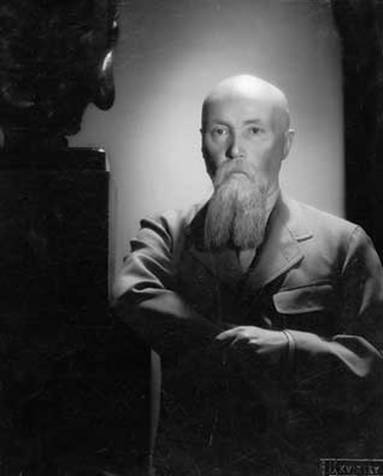

Nicholas Roerich. May,

1934. Shanghai, China

In fact, Bokii, who was arrested and executed in 1937, became a

victim of a similar case that was totally made up by his former colleagues

who sought to destroy him on the orders from Stalin. Bokii’s interest in occult and mysticism and

participation in Barchenko’s United Labor

Brotherhood in the 1920s were used as a jump start to invent a more

sinister plot. The plot involved a tale about the anti-Soviet secret

society called Shambhala, with branches allegedly

all over the world. This society planned to murder comrade Stalin. It was

totally bizarre. Stalin hated Bokii anyway. As

one of the bosses of the secret police, Bokii

supervised phone wiretappings and radio surveillance and had files on all

Bolshevik elite. Stalin knew he had all this information and wanted to

eliminate the chief of the Special Section. So the occult games that Bokii had played during the 1920s were used against him

in 1937. It was just an excuse to eliminate him.

Barchenko was the

last one to be shot. There was a whole group of them, who were supposedly

part of this secret society of Shambhala. And Barchenko was the only one who was fighting for his

life to the end. He tried to intrigue his investigators by presenting

himself as a valuable scientist – an asset that could very useful to the

Bolshevik state. When the “investigation” was nearing its end, Barchenko suddenly started claiming to have discovered

a mysterious biological weapon. This delayed the execution, but eventually

he couldn’t avoid it. He was executed too. Of course, Hitler did the

similar things in Germany

with former occultists. When he was still maturing, during the 1920s, he

dabbled a bit into these esoteric groups. But when he came to power,

he outlawed all of them. Because in a totalitarian dictatorship there can

be only one master, only one cult.

PoS: Do you think communism and these

spiritual interests were compatible?

AZ: Well, Bokii’s interest in the Shambhala

myth was coming partly from the fact that his communist idealism had begun

to crack. He was an idealist. He expected that when in 1917 the

Bolsheviks came to power, a golden age would arrive. People would be

all brothers and sisters. They would stop stealing. They would love each

other. The beasts and their prey would embrace each other. But it didn’t

happen. Then in 1921, when the Red sailors at Leningrad – who had been the backbone of

the Revolution – revolted against the Bolshevik regime, and the revolt was

suppressed, he had a nervous breakdown. He might have started saying to

himself: “my goodness, we killed so many people in the civil war; half of

the nation was destroyed to build a new society.” And it was justified on

the basis that you cannot make an omelet without breaking eggs, but now

there was no omelet. I assume that this is when he became interested in Barchenko.

People are

sometimes surprised that Bokii, a die-hard

Bolshevik, suddenly turned toward the occult. But part of the reason is

because he thought maybe if they go to Tibet they might uncover some

secret knowledge, some techniques that could show Bolsheviks how to sway

the minds of the people toward Communism and make people better. In

case of Bokii and Barchenko

it is all about the mind-bending. The Bolsheviks had taken power and they

were building socialism. This was all right. But the two friends were

disturbed by the fact that the minds of the people were still infested with

old prejudices. So they were posing a question for themselves, “How can we

transform the minds of the populace?” That is how they eventually became interested

in the Shambhala legend. In their view, it could

contain some high knowledge that they can bring back to Red Russia and use

to spearhead Communism. In other words, unlike people like Ungern or Bolshevik fellow-travelers in Mongolia,

who were more interested in using martial sides of the Shambhala

prophecy, Bokii and Barchenko

were eager to use the inner spiritual aspects of that legend. Barchenko claimed to have known Tibet, and

so they tried to organize an expedition. Readers can find out what happened

later by reading my book.

Source: People of Shambhala

– in: http://peopleofshambhala.com/buddhists-occultists-and-secret-societies-in-early-bolshevik-russia-an-interview-with-andrei-znamenski/

See also from Andrei Znamenski

Red_Shambhala – Magic, Prophecy, and

Geopolitics in the heart of Asia

Totalitarian Temptation – Andrei Znamenski

talks about his latest book Red Shambhala

New Opium for

Intellectuals: Tibetan Buddhist Chic in the West

|